Bird Watching Basics

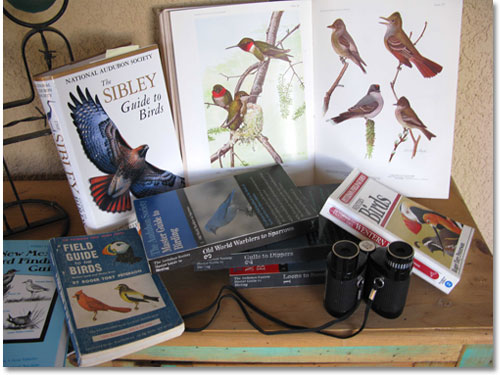

A few of the birders' tools - a good pair of binoculars, Field Guide to Birds, The Sibley Guide to Birds

- Finding the Birds

- A Bird Watching Journal

- A Backyard Bird Sanctuary

- Bird Photography

Be forewarned.

Drawn by the adventure of bird watching, you may sit for hours on your back porch waiting for a Bullock's Oriole to sip nectar, like fine wine, from the blooms of your trumpet vine. You may hike for miles through southeastern Arizona's forested Chiricahua Mountains in search of the Elegant Trogon. You may sit in the pre-dawn darkness beside a high desert wetland on an icy winter morning to watch migratory water birds rise from the water's surface on the first rays of the sun. You may wade through estuarine swamplands in search of a Roseate Spoonbill. You may explore tropical rain forests, where you will find some of the most diverse bird populations in the world. You may dress dowdy, giving up the bird-frightening colors of the Paris boardwalks. You may have to add a whole new shelf in your library to make room for new field guides on birds. You will likely find a new ethic in your relationships with wildlife. Along the way, you may make eccentric new bird-watching friends (or become an eccentric new bird-watching friend).

Scrub Jay

One thing is certain, you will discover a whole new dimension to the meaning of adventure.

- Watching Birds and Seeing Birds

- Identifying Birds

- Dressing for the Occasion (what to wear in the field)

- Field Guides

- Ethics

- A Few Bird Facts

Watching Birds and Seeing Birds

You will advance to a whole new level in the art of birding when you reach beyond the simple identification of a species. "In fact," said Claudia Wilds in the Audubon Society's Master Guide to Birding, "this is the time to start looking." She recommends that you study the bird as if you "will soon be asked to describe or even draw it." You should, she says, look first at the eye, and "try to ascertain the color of the iris." You should "study the size and shape of the bill…" You should study the bird's proportions, its coloring and patterns. "You will soon discover," said Wilds, "that you can memorize birds in much the same way you memorize human faces."

White-winged Dove

Identifying Birds

Birds, you will find, sometimes defy certain identification, as David Allen Sibley points out in his book The Sibley Guide to Birds. For instance, birds of the same species may vary in subtle ways across a range or from range to range. Colors and patterns vary among adults and juveniles, males and females. Plumage may vary as feathers wear and fade. Silhouettes may vary between males and females. Hybrids sometimes occur when closely related species interbreed. Nevertheless, you can still use the distinctive traits – for instance, size, silhouette, plumage color and pattern, behavior and songs and calls – shared by birds of the same species as clues to identification.

Obviously, you can compare sizes to distinguish between disparate species such as a Western Bluebird and a Red-tailed Hawk, but you can also compare sizes to distinguish between the more closely related species such as a Ground Dove and a Mourning Dove or a White-winged Dove or a Rock Dove. You can use silhouettes to tell the difference between, say, a Swallow-tailed Kite and a Black-tailed Hawk, although both have comparable lengths and wing spans. You can rely on the colors and patterns of plumage to identify the Scrub Jay, the Piñon Jay and the Mexican Jay, although they all have similar sizes and silhouettes. You can identify many birds by their behavior, for instance, the undulating flight of various woodpeckers, the businesslike scurrying of the Gambel's Quail, the pompous courting displays of the Boat-tailed Grackle. While it would be roughly akin to learning the score of Barber of Seville in Italian, you will find, as Wilds said, that "Knowing the songs and calls of a region's birds will enable you to identify a far higher percentage than you could with binoculars alone."

Dressing for the Occasion

As your passion for the birds grows, you will likely begin dressing in the shades of the soils, the rock formations and the foliage, giving up the bright colors of the city. You will wear practical and durable cottons and wools and, on foul winter days, rain gear and long underwear rather than rustling and snag-prone taffeta dresses and silk suits. You will take to sensible shoes and boots rather than high heels and Guccis.

Field Guides

You will discover a number of excellent field guides at just about any general book store. For instance, Roger Tory Peterson, renowned naturalist of the 20th century and inventor of the modern field guide, produced indispensible books on American bird populations. The Audubon Society, working with preeminent authorities, has produced a substantial list of field guides, including the treasured three-volume set Master Guide to Birding. (Unfortunately, Master Guide to Birding is, as far as I can discover, now out of print, but you can still find it in used book stores and on the Internet.)

A New Ethic

Your increasing appreciation for the birds will likely spawn a new ethic. "In all situations," said Sibley, "you must first consider the welfare of the birds. Avoid making a disturbance, especially at roosting and nesting sites. Tread lightly and encourage others to do the same."

Red-tailed hawk up close.

A Few Bird Facts

- Flying dinosaurs gave rise to the earliest birds some 150 million years ago.

- Today, some 10,000 species of bird populate our planet, with roughly ten percent of them occurring in the continental United States and Canada.

- During migratory seasons in the U. S. and Canada, hundreds of millions of birds follow a complex system of routes that pass through four north-south corridors: the Atlantic Flyway, the Mississippi Flyway, the Central Flyway and the Pacific Flyway. At the height of the seasons, they bring extraordinary bird-watching opportunities.

- The Arctic Tern may migrate all the way from the Arctic to the Antarctica and return every year during its life, which may span two decades—a lifetime distance of some 400 thousand miles. It ranks at the top of the list in migratory range.

- The Wandering Albatross (native to the Antarctic) has the largest wingspan of all the birds, 11 feet or more; the Bee Hummingbird (from Cuba), the smallest, some 1.25 to 1.5 inches.

- The Ostrich (from Africa) lays the largest egg in the world (two pounds or more), hummingbirds, the smallest (a few hundredths of an ounce).

- The Peregrine Falcon can fly well over 100 miles per hour, making it the fastest of all the birds.

For information on other aspects of birding, see

Finding

the Birds

A Bird

Watching Journal

A Back Yard Bird Sanctuary

Bird

Photography.

Bird Watching Tips & Interesting

Facts about Birds

Bird Watching at the Salton

Sea

Wildlife Viewing at Coyote Canyon in Anza Borrego

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms