Grand Circle Part 3

Land of Canyons

by Jay W. Sharp

You can call me a heathen, I guess, especially if you take the viewpoint of Brother White, pastor of the church I attended when I was growing up in a small town in the Rolling Plains of Texas, but I must tell you that I do feel a sense of reverence when I think about the galaxy of canyons across southern Utah. Rather than Brother White’s preachings from the pulpit, I’ll take my sermons in stone.

The Land

Utah’s canyons, in the northwestern part of the Great Circle, on the Colorado Plateau, give eloquent testimony to their geologic history. Venturing into the land of the canyons, you will discover sinuous and labyrinthine gorges, eerie slot canyons, monumental sandstone arches and natural bridges, towering monoliths, isolated buttes and mesas, veritable sculpture gardens, great sand dunes and volcanic landscapes—each a chapter in a story that began 600 million years ago.

The Colorado Plateau itself, spanning some 140,000 square miles, speaks to colossal forces that lifted the entire landform like an elevator for thousands of feet. Stratified canyon walls tell of advancing and retreating seas that laid down thick beds of sediments atop the plateau. Gorges, arches, spires, buttes and stone monuments reflect the infinitely relentless work of flowing streams, spalling rock and gravity. The sand dunes comprise the debris from erosion. The volcanic landscape, primarily in the western part of the Colorado Plateau, recalls a time when molten rock and ash erupted violently from the earth’s interior and spread across parts of the countryside.

If you happen to be a spiritual descendent of the likes of Emerson, Thoreau, Abbey, Leopold or Bedichek, you will find that the sculpted land of southern Utah will draw you into its heart, luring you with an compelling call to adventure, discovery, solitude, mystery and reflection. In the Canyonlands – the name for the eastern part of the region – you can explore three national parks, several national monuments, a national recreation area, various state parks and isolated sanctuaries. In the High Plateau – the western part of the region – you can visit two more national parks, still more monuments and state parks and a national forest.

Parks and Monuments of the Canyonlands

In the Arches and Canyonlands National Parks, both near Moab, the agents of erosion cut the features from the same pieces of 100- to 300-million-year-old sedimentary geologic cloth, but they used different patterns.

In the 74,000-acre Arches National Park, water and spalling, working in partnership with gravity, have carved more than 2000 sandstone arches – the greatest concentration in the world – features that rise like rainbows of stone above the landscape. Moreover, according to a Geologic Resource Evaluation report produced by the U. S. Department of Interior, “a collection of balanced rocks, fin-shaped rock features, rock pinnacles, folded rock strata draped over salt diapirs [a geologic formation], stark exposures of millions of years of geologic history, petrified sand dunes that once swept across a desert landscape millions of years ago, evidence of a sea that once drowned eastern Utah, and a maze of deep narrow canyons grace the park.”

In the Canyonlands National Park, four and a half times larger than Arches National Park, Nature’s sculptors have carved a couple of 2000-foot-deep gorges (cut by the Colorado and Green Rivers), thousands of smaller canyons and a dazzling array of stony icons. They have divided the park into three major districts: Island in the Sky, a 1000-foot-high dissected mesa with one of the most scenic drives in North America; Needles, a mind-numbingly complex landscape of sandstone pillars, domes, arches and narrow canyons; and the Maze, one of the most rugged and isolated areas in the American Southwest. “I feel myself sinking into the landscape” said Edward Abbey in Desert Solitaire.

To the west of Arches and Canyonlands National Parks, Capitol Reef National Park – named for a cluster of capitol rotunda-shaped rock domes – embraces and protects the Waterpocket Fold, a north-to-south upward warp in the earth’s crust. Produced by the same forces that lifted the Colorado Plateau, “The Fold,” says The Away Network Internet site, “is the defining geologic formation that makes up Capitol Reef National Park, a 100-mile stretch of buckled earth characterized by crimson cliffs, soaring spires, massive domes, serpentine canyons, graceful arches, stark monoliths and silence.”

In addition to the national parks of the Canyonlands, you have the opportunity to visit a host of other spectacular sites, for example: the 6500-foot-high Natural Bridges National Monument, a comparatively remote and less traveled area with three towering natural bridges that span meandering streams; the Rainbow Bridge National Monument, an isolated and, to the Native Americans, a sacred site with a 290-foot-high natural bridge, the tallest in the world; the 2600-square-mile Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, a canyon-laced area so rough and isolated that it was the last region in the U. S. to be mapped; the 2000-square-mile Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, a Martian-like landscape of bare red sandstone gorges and cliffs that embrace the Lake Powell reservoir, with its 2000-mile-long shoreline; the small Goblin Valley State Park, a setting with a cast of strange mushroom-shaped stone figures and skeletal-like cliff faces; Gooseneck State Park, a tightly wound 1000-foot deep gorge cut by the San Juan River; the 8-square-mile Dead Horse Point State Park, a high peninsula of land overlooking canyons carved by the Colorado River, 2000 feet below; and the San Rafael Swell, “a seldom explored wilderness area containing many narrow canyons amidst great expanses of colourful slickrock with arches and natural bridges, cliffs, ridges and mesas,” according to the American Southwest Internet site.

Parks and Monuments of the High Plateau

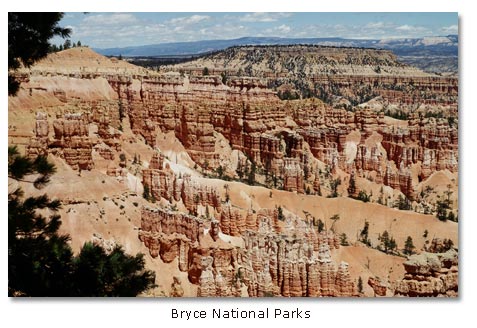

In the 35,835-acre Bryce Canyon National Park, east of Cedar City in the High Plateau region, you can see, occupying a complex of U-shaped amphitheaters, perhaps the world’s largest cast of hoodoos—pillars of stone shaped like the pawns of a chess set. The hoodoos exude a sense of the ethereal, like a creation by an otherworldly force. The bewitching, undulating shapes led the Paiute Indians to believe that the hoodoos had once been evil creatures who could transform themselves into people—until Coyote (frequently the “Trickster” in the folk stories of the prehistoric Southwest) changed them all into stone. Coyote left them frozen in place like Lot’s wife, who turned into a pillar of salt when she dared look back at God’s destruction of the evil city of Sodom. By contrast, the shapes have led geologists to believe that water has carved the hoodoos in a process called differential erosion, in which softer rocks of the columns wear away more rapidly than harder rocks, leaving the undulating forms standing in place like Lot’s wife.

In the 147,000-acre Zion National Park, located south of Cedar City and on the western edge of the Colorado Plateau, you can trace the geologic history of the region like you would read the middle pages of a book. Zion’s highest strata correspond with Bryce’s lowest strata. Its lowest strata correspond to Grand Canyon’s highest strata. Its middle strata tie the geologic story into a whole. Located at the edge of the Colorado Plateau, Zion’s streams, over millions of years, have cascaded with gathering power down the steepening slope of the rising landform, cutting deep canyons, triggering landslides and reshaping the landscape in a relentless rush to the Colorado River and the sea. “Nothing can exceed the wondrous beauty of [Zion],” said Captain Clarence E. Dutton in a U. S. Geological Survey report in 1881. “in its proportions it is about equal to Yo Semite [Yosemite], but in the nobility and beauty of the sculptures there is no comparison.”

Beyond Bryce and Zion National Parks, you can visit Cedar Breaks National Monument, a 2000-foot-deep natural amphitheater with a forested rim and sculpted walls; Pipe Springs National Monument, a living history exhibit of Indian and frontier life in the region; the Escalante State Park, a colorful geologic jigsaw puzzle of sculpted forms, “creeping” boulders, volcanic debris and petrified trees; and the Kodachrome Basin State Park, a colorful kaleidoscope of carved canyon walls and cylindrical stone columns.

In addition to the parks and monuments in the High Plateau, you can find a true wilderness experience in the 2,000,000-acre Dixie National Forest, an area distinguished by its diversity and its isolated enclaves. At the lower elevations, about 2800 feet, the forest receives about 10 inches of precipitation and supports only a sparse desert-like community of plants and wildlife. At the upper elevations, over 11,000 feet, it receives some 40 inches of precipitation (primarily snowfall) and supports woodlands of conifers and aspen. It experiences summer temperatures of 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the lower elevations and winter temperatures of 30 degrees below zero in the higher elevations. In its canyon walls, you discover sculpted features and colors much like those you will see in the parks and monuments, and on Boulder Mountain, a high-elevation plateau, you will find hundreds of small lakes and ponds, jewels in the forests.

Prehistoric Spiritualists

The land of canyons – raised, fractured, folded and carved – gives stark testimony to the work of universal and timeless forces, and it instills in the human mind, primal and modern, a sense of reverence and wonder. You will see the evidence in the mystical figures engraved, chiseled and painted on cliff faces and boulders by nomadic hunters and gatherers, early village farmers, Puebloan peoples and raiding tribes who sought spiritual sustenance in an awesome world.

Since rock art sites serve modern Indian peoples, for instance, the Navajos, for ceremonies and ritual, we can imagine that the images served earlier peoples in a similar way. We might presume, for instance, that the figures may have functioned as shamans’ gateways to the spirit world, a community’s plea for a bountiful crop or a successful hunt, a family’s celebration of human passages, or a culturally related group’s record of a mythical event. However, as F. A. Barnes said in Canyon County Prehistoric Rock Art, “it is quite likely that not even the application of the best available scientific logic will produce reliable information about the actual meanings and uses of specific designs or panels of Southwester prehistoric rock art.”

As you explore the abundant rock art sites across the canyon country, you will find, for example, mysterious realistic and stylized images of sacred and mythical figures, ceremonial masked dancers, migrations, warriors, agricultural and hunting scenes, game animals, weapons, symbolic icons, planets or stars, and geometric shapes. “The enormous diversity in Southwest rock art,” said preeminent authority Polly Schaafsma in her Indian Rock Art of the Southwest, “reflects the complexity of southwest prehistory and of the ideologies and ritual and social functions in which rock art played a part.”

For instance, according to Kevin L. Callahan, “An Outline of Utah Rock Art,” Upper Midwest Rock Art Research Association Internet site, you may see a diversity of geometric shapes produced by hunting and gathering bands as much as 8000 years ago, a couple of millennia after the end of the Ice Ages; distinctively shaped images of humans and animals left by hunters and gatherers 5000 years ago; life-size, ghostly figures of humans and animals painted by the founders of the Puebloan traditions some 2000 years ago; figures of elaborately costumed and bejeweled humans painted and chiseled by Puebloans 7 to 17 centuries ago; and representations of people and animals of European origin rendered by the historic Ute and Paiute

Tribes.

A few of the places where you can visit outstanding rock art sites include Arches National Park, in Courthouse Wash; Canyonlands National Park, in the Needles and Maze districts; Capitol Reef National Park, along the Fremont River; Zion National Park, near the numerous Anasazi cliff dwellings; Sand Island, near the San Juan River south of Bluff; San Rafael Swell, in several canyons; and, among the most famous, Newspaper Rock State Park, between Monticello and Canyonlands National Park.

Sermons in Stone

The land of canyons is a library of geologic history, a summons to adventure and wonder, and a challenge to the human intellect. The sculpted chasms and landforms validate what Richard Ordway said years ago in his Earth Science: “Mountains, hills, plateaus, and valleys are not permanent features of the Earth’s surface but only temporary forms in an ever-changing pattern. Rocks are not dead, inert, and unchanging; they are alive with messages about a geologic history that stretches backward into time for many hundreds of millions of years. There really are ‘sermons in stones’ for anyone who knows how to decode the records…”

More Information, Canyonlands Region

Arches National Park

Bryce Canyon National Park

Canyonlands National Park

Capitol Reef National Park

Cedar Breaks National Monument

Grand Staircase-Escalante NM

Natural Bridges National Monument

Rainbow Bridge National Monument

Zion National Park

Places to Stay, Canyonlands Region

Places to Stay, High Plateau Region

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms