Four Corners And The Grand Circle

The Parks of The West

by Jay W. Sharp

Every time you explore the Four Corners section of the Grand Circle, you will turn up new aspects of Nature’s power, elegance and timelessness. You will uncover new insights into the human experience. You will see more evidence of our predecessors’ spiritual bond with Mother Earth, the planets and the stars. You will experience the excitement of discovery.

The Land

The product of hundreds of millions of years of crustal uplift, mountain building, climate changes and relentless erosion, the Four Corners area spans a diverse landscape, a part of the Colorado Plateau. In southwestern Colorado, for example, the San Juan Mountains rise more than 14,000 feet, with a tundra environment at the peaks, alpine forests and meadows in the higher slopes, and Ponderosa Pine forests in the lower flanks. To the south and west, the arid landscape – extending into New Mexico, Arizona and Utah – ranges from mesas covered with Piñon Pines, to flats blanketed with sage, to pink sand dunes built by the winds, to canyons deeply cut into barren red sandstone. The occasional flowing streams draw the cottonwoods and, now, the aggressively invasive Russian Olive and Tamarisk to their banks.

If you hike the higher wooded elevations of the San Juans in late summer, you will pass through dark and somber forests and emerge into sun-washed alpine meadows, surrounded by wildflowers as rich in color as the palette of a French Impressionist.

Between Durango and Pagosa Springs, off U. S. Highway 160, you will come to Chimney Rock, a pair of 1000-foot-high pillars, flanked by talus slopes, carved by water from sedimentary rock deposited by a shallow sea some 70 to 100 million years ago. The lofty columns hold a virtual library of the geologic history of ancient changing shorelines and rushing rivers. They stand as a regional landmark, often an ethereal presence, on a distant horizon.

A drive south from Farmington, New Mexico, on State Highway 371 for 30 to 35 miles will take you to the 4000-acre Bisti Wilderness, an isolated area where you can spend a day hiking through an otherworldly sculpture garden of reddish, gray, yellow, cream and black mounds, spherical boulders, billowing stone landforms, mushroom-shaped formations, and hoodoos (stone pedestals with flat shale caps). As you walk across the desert floor, you will see fossilized remnants of a rain forest, which recalls a 70-million-year-old chapter in the geologic history of the region.

Should you drive west on U. S. Highway 64 from Farmington, some 40 miles into the Navajo reservation, you will see the 1700-foot high landform called Ship Rock, or Tse Bitai, the “Winged Rock” in the Navajos’ Athapaskan language. It originated as molten rock that filled the vent of a volcanic crater some 30 million years ago. It solidified and hardened, remaining standing after the softer enshrouding crater material eroded away. It lies at the center of six radiating dikes, sheet-like bodies of igneous material that intruded upward, into strata of surrounding rocks.

An hour’s drive west from Gallup, New Mexico, on Interstate Highway 40, will bring you to Arizona’s Petrified Forest and Painted Desert, a 218,000-acre national park.

Walking the trails through the Petrified Forest, you will see one of the world’s largest and perhaps the most colorful deposits of petrified wood. It speaks to events 225 million years ago, when floodwaters transported downed trees from a wooded area to a flood plain, where they came to rest and fossilized over time. Wandering the trails of the Painted Desert, immediately to the north of the Petrified Forest, you will pass through some of the most colorful rock and soil landscapes in the world. They take the forms of mesas, sculpted buttes, rolling badlands and cross-bedded sandstone hills.

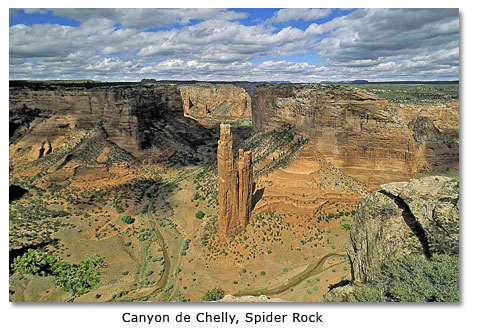

Sixty air miles north northeast of Petrified Forest and Painted Desert you come to Canyon de Chelly National Monument, a complex of three vertical-walled, 1000-foot deep gorges sculpted from red sandstone and red granite by the Rio de Chelly and its tributaries. The prehistoric home of nomadic hunters and gatherers and Anasazi Puebloan peoples and the historic home of Navajos, Canyon de Chelly ranks as a masterpiece of geologic grace and elegance. From Chinle, a predominantly Navajo community at the mouth of the canyon, you can drive along the northern and southern rims of the canyon walls, following roads with pullouts that give you an overview of the canyon, and you can make arrangements to make a driving tour, accompanied by a Navajo guide, through the canyon floor, with the sandstone walls soaring above you on either side.

If Canyon de Chelly has been carved into the earth, the Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park, 70 air miles to the northwest, on the Arizona/Utah border, has been carved from the earth. Seeing the soaring red sandstone and shale buttes and stele-like formations for the first time, you may feel a sense of déjà vu. You are looking, after all, at one of the most famous landscapes on earth, courtesy of John Ford, John Wayne and Eastman Kodak.

In the southwestern corner of Colorado, on the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, you will find the Sleeping Ute Mountain, nearly 10,000 feet in elevation, with contours that bear a Rodin-like resemblance to an exhausted man lying across the horizon. Looking at the mountain in the light of dawn or of twilight, you may feel a sense of powerful spirituality in the languid form.

The Early People

As you explore the mountain talus slopes, mesa tops, canyons and flat lands of the Four Corners region, you will discover a compelling story of prehistoric man, told more vividly, in five major chapters, than any other place in the United States.

The earliest arrivals, called Paleo Indians, appeared sometime during the latter millennia of the last Ice Age, the Wisconsin Glaciation, which lasted for a thousand centuries and ended roughly 10,000 years ago. Nomadic hunters of the big game animals, including mastodons, mammoths and the longhorn bison, the Paleo Indians traveled by foot in small bands, carrying all their belongings on their backs. They camped in shallow caves, possibly in temporary brush or hide shelters, oftentimes in the open landscape. Presumably, they wore clothes made of animal skins and plant fibers.

They made tools and camp and personal gear from stone, bone, sinew, leather, wood and plant fibers. In the early days, they may have hunted by driving herds of large animals over edges of precipitous cliffs or canyon walls. Later, they adopted the spear, with a stone point, making themselves more selective and efficient hunters. They probably trapped or bludgeoned smaller animals. They not only hunted, they likely preyed, opportunistically, on newborn and ailing animals. They certainly ate plant seeds, roots and fruits. Bands probably gathered periodically to renew acquaintances, practice ancient rituals, arrange marriages, exchange trade goods and report the latest gossip. Remarkably, the Paleo Indians, widely scattered over a primal landscape, managed to maintain a cultural continuity that lasted for thousands of years, possibly for longer than all the other, succeeding cultures combined.

When the Ice Ages ended and the big game animals died out, the Paleo Indians in the Four Corners region, as in the rest of the Southwest, had to change age-old subsistence patterns and traditions. They had to redefine themselves, turning to smaller animals and, increasingly, to plants for food. Now called Archaic Indians, they calibrated their lives, not to the movement of big game, but to the ripening of wild food plants. Early on, they apparently spent winters in the lower elevations, near streams and playas, and they spent springs and summers in the mountains gathering wild plants. They took shelter and wore clothes much like their predecessors, the Paleo Indians. They did, however, develop a new tool suite, which was more suited for harvesting wild plants.

The men still used stone-tipped hunting spears, hurling them at prey with an atlatl, or throwing stick, with considerable propulsive force. Around 5000 to 6000 years ago, the desert Archaic peoples began a more profound change, adopting the first notions of village life, more substantial shelters, rudimentary agriculture, changed hunting patterns, expanded trade, and apparently began cherishing art. Their population began to increase. As the millennia passed, the Archaic peoples grew more sedentary, more culturally diversified, becoming village farmers, growing corn, beans and squash—crops with origins in Mexico. They developed simple water management systems. They built more storage spaces for caching increased food stores. They developed social stratification, leaving grave offerings for revered individuals. They apparently developed a higher interest in the spiritual dimension of life, for their shamans began leaving more images – gateways to the spirit world – painted or chiseled on surfaces of stone.

By the beginning of the first millennium, the prehistoric peoples of the Four Corners region had largely given up nomadism in favor of agriculture, although they would never completely abandon the hunt or wild plant collection. Distinguishing themselves by the artistry of their baskets, which they wove from plant fibers, these people became known as the Basketmakers. They lived in hamlets of pithouses (structures built over an earthen pits) or in caves or rock overhangs along canyon walls. They dug bell- or egg- shaped storage bins in the floors of their lodges. They wore clothing fashioned from leather and turkey feathers and shoes made from plant fibers.

They wore jewelry made from stone, bone and shell. Early on, the Basketmakers, like their predecessors, the Archaic hunters, used the spear and atlatl. They eschewed pottery, played games, smoked cylindrical pipes and carved wooden flower blossoms. They buried their dead with grave offerings. About the middle of the first millennium, the Basketmakers began building larger villages, with more substantial lodges and increased storage. They began constructing kivas—semisubterranean chambers presumably used for community functions and rituals. They domesticated the turkey, which joined the long-domesticated dog in the hamlets. The men, at last, gave up the spear and atlatl in favor of the bow and arrow. The women finally turned to making and using pottery, allowing their basket-making skills to diminish. The Basketmakers laid the foundation for the rise of the Puebloan peoples called Anasazi, who would command center stage in the Four Corners region beginning in the latter centuries of the first millennium.

While the earliest Anasazi continued to build traditional pithouse villages, they also began to construct simple surface structures of wood or masonry. They upgraded farming practices and improved water management, increasing the yields of their crops. Restless spirits, they moved every few decades, possibly because of resource depletion, drought, social distress or simply greener pastures. Near the end of the first millennium, the Anasazi, apparently inspired by vigorous leadership and by outside influences, gave up ancient traditions centered in hamlets of pithouses and simple surface structures and turned to a new lifestyle formed by elaborate communities of multi-story stone buildings, open plazas and large ceremonial chambers. They developed signature skills in community planning, architecture and consummate masonry; constructed a system of roads; cultivated their abilities in communication (using signal fires and reflective obsidian slabs); perhaps established a regional system for managing food supplies; perfected the craft of jewelry making; created a social structure with an aristocracy; refined their abilities in astronomical observation; and elevated the importance of religion and ritual. Beginning in northwestern New Mexico, the Anasazi cultural revolution swept across the Four Corners region.

Strangely, for reasons poorly understood, the Anasazi largely abandoned the Four Corners during the 13th and 14th centuries. Many of the people moved east and south, into the upper Río Grande drainage, where they built large new Puebloan communities that would one day greet conquistadors and settlers from Spain and Mexico.

As most Anasazi people abandoned Four Corners, other peoples, for instance, the Navajos and the Utes emerged as dominant cultural forces in the region. At some uncertain point in time, possibly in the last quarter of the first millennium, the Athapaskan-speaking Navajos came from the northwest, probably filtering into the Four Corners area as small bands of nomadic hunters and gatherers. Influenced by the Puebloan peoples on the upper Rio Grande, the Navajos grew patches of corn, beans and squash to supplement their diets. Influenced by Spanish colonists, they raised herds of sheep, goats and horses. They lived in forked-stick lodges called hogans, often clustered on high mesas near their fields. They formed alliances among their bands and with the Puebloan peoples to defend themselves against the Spanish and the Utes.

Like their forebears, they followed the practice of raiding, although not for personal glory or vengeance, but rather as a commercial venture. Later, they Navajos would become known as masters of weaving and jewelry making. The Utes – the Blue Sky People – may have emerged from the ancient hunter/gather traditions indigenous to the Four Corners region, although they spoke a Uto-Aztecan language, which presumably had roots far to the south, deep in Mexico. Moving in small bands, they hunted and trapped game. They lived in willow brush lodges. A Ute warrior wore a leather shirt, a breechclout, leggings and moccasins, and a Ute woman wore a leather poncho-like blouse and a leather skirt and moccasins. They became highly skilled at leatherwork and basketry. Among the first to acquire horses after the arrival of the Spanish, the Utes became fearful mounted raiders. They fought the Navajos. They formed alliances of convenience with other tribes to do battle with Puebloan peoples and the Spanish.

The Spiritual Connection

The Indians peoples of the Four Corners region left a tantalizing and mysterious record of their transcendent spirituality, which often flowed from the passage of planets and stars and the coming and going of the seasons. From the time of the hunters and gatherers, for example, the people left figures of deities, star patterns and symbols scribed and painted on stone surfaces in canyon walls and boulder fields. The Anasazi of Chaco Canyon oriented their pueblo and kivas to catch the rays of the rising sun at summer solstice. They built a pueblo village at Chimney Rock to celebrate the lunar standstill, the moment – which occurs every 18 years – when the moon reaches its maximum distance north of the plane of earth’s orbit around the sun. The Navajos believed that Ship Rock was location where deities called Warrior Twins defeated giant predatory birds in a titanic battle, making the earth safe for the people. The Utes believed that Sleeping Ute Mountain was a great warrior who fought “evil ones” in a terrible conflict then laid down for a long rest, changing his “blankets” – the snow cover and seasonal vegetation – to herald the changing of the seasons.

The Discovery of Self

In the Four Corners region, you – and your children – not only have the opportunity to visit and explore the ruins in extraordinary settings. You can visit ancient living pueblos and reservations. Whether you are an novice or an avocational archaeologist, you can – working with experienced professionals – learn the history, perfect prehistoric skills, join excavations, do archaeological research and analysis, and make Native American friends.

The spirit of the Anasazi tradition emerged at Chaco Canyon, in northwestern New Mexico, where you can find some one dozen “Great Houses” distinguished by carefully planned, astronomically aligned, multistory structures; stylish architectural features; Great Kivas; extraordinary masonry and decorative veneers; colonnades (a MesoAmerican influence?); plastered walls and mural paintings and crypts; jewelry and ornament caches; abundant ceramic vessels; a radiating road system; a great (possibly processional) staircase; and a great hiking trail. Chaco Canyon became the Rome of the Anasazi region.

The pinnacle of Anasazi community planning arose at Mesa Verde, in southwestern Colorado, where you can explore multistoried dwellings so carefully sequestered within deep canyon alcoves that they seem like an integral part of Nature’s monumental sculpture. Perhaps the most glorious setting for Anasazi communities would be Canyon de Chelly, in northeastern Arizona; the most pristine, Navajo National Monument ruins, in northeastern Arizona; the most mysterious, the Hovenweep ruins, in southeastern Utah and southwestern Colorado.

In spite of the widespread abandonments in the Four Corners region during the first half of the first millennium, the Acoma Pueblo, some 70 miles west of Albuquerque, and 12 Hopi villages in northeastern Arizona remain populated to this day by living descendents of the Anasazi. At Acoma, spectacularly situated on the crest of a 350-foot-high mesa, you can tour ancient structures and streets, visit a Spanish-colonial era mission church and see village festivals. At the Homol’ovi Ruins State Park, just south of the Hopi Indian Reservation, near Winslow, you can meet Hopi craftsmen and visit the ruins, which are on the National Register of Historic Places. You can tour a couple of the Hopi villages that are still occupied.

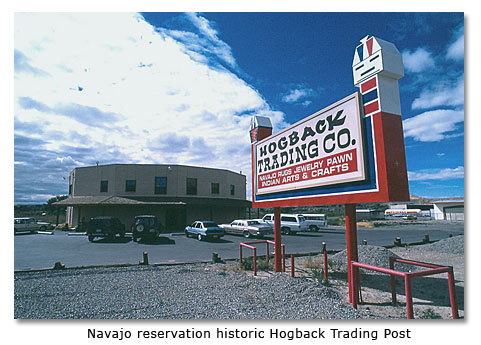

Driving across the Navajo Reservation – which spans northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah and northwestern New Mexico – you will find the signature of the Navajo people across the land, in the traditional eastward-facing hogans in canyons and on the flats; in sweat lodges adjacent to modern homes; among the women in traditional dress; in sheep flocks watched over by shepherds and their dogs; in crafts stores, trading posts and pawn shops stocked with exquisite rugs and turquoise and silver jewelry; and on radio stations with Athapaskan-speaking announcers and changers. You can make arrangements for visiting historic Navajo sites by contacting the Aztec Archaeological Consultants, Aztec, New Mexico, or the San Juan County Archaeological Research Center at Salmon Ruins, Bloomfield, New Mexico (See contact information below).

To visit the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, in southwestern Colorado, you will have to make arrangements for guided tours, hikes and lectures to gain access to places such as the Sleeping Ute Mountain. In fact, as Deb Acord said in the Colorado Springs Gazette (April 21, 2006), “The only way to get in and find your way around is with a Ute guide who knows where to find some of the park’s treasures—hundreds of petroglyphs [images scribed or pecked into stone surfaces], some dating back to the ancient Pueblo Indians who lived here and some more recently created by the Utes themselves; land strewn with pieces of ancient pots and tools; the remnants of kivas dug into the hard clay and gravel; and cliff dwellings built into the rock like Medieval castles.” See contact information below.

Should you wish to go beyond the heritage tourist level, you can contact any of a number of consulting firms or archaeological societies. You may find the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, near Mesa Verde, one of the most rewarding prospects. According to Crow Canyon President, Dr. Ricky Lightfoot, “If you have ever dreamed of being an archaeologist excavating in the ruins of an ancient civilization and analyzing the artifacts you found, then Crow Canyon is the place for you.

“Crow Canyon has learning opportunities for just about everyone, from adults to teenagers, from teachers to schoolchildren, and from families to aspiring young professionals in archaeology and education… Whether you are an elementary school student, a senior citizen or somewhere in between, Crow Canyon has a program that will engage you in the adventure and excitement of archaeological discovery.”

More Information

Chaco Culture National Historic Park

Chimney Rock Archeological Area

Mesa Verde National Park

Monument Valley Tribal Park

Petrified Forest National Park

Canyon De Chelly National Monument

Navajo National Monument

Hovenweep National Monument

Acoma

Places to Stay

Cortez, Colorado

Durango, Colorado

Blanding, Utah

Farmington, New Mexico

Gallup, New Mexico

Holbrook, Arizona

Winslow, Arizona

Kayenta, AZ,

You will also find many camping opportunities. My wife and I have, for example, camped at Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Canyon de Chelly, the Navajo National Monument, Hovenweep and various other locations, some of them very isolated, in the region. Removed from the glow of city lights and the din of city traffic, we found the nights serene, the skies deep black, the stars brilliant. Once, at Chaco Canyon, we had a visitor in the night, a coyote that tried to put his nose into the zippered doorway of our tent. My wife had no sense of humor whatever about that incident. But that, as they say, is another story.

Grand Circle Part 1

Grand Circle Part 3

Grand Circle Part 4

Arches National Park

Bryce Canyon National Park

Canyonlands National Park

Canyon De Chelly National Monument

Grand Canyon National Park

Montezuma Castle National Monument

Monument Valley

Mesa Verde National Park

Zion National Park

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Your GPS Navigation Systems

May Get You Killed

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Desert Survival Skills

- Successful Search & Rescue Missions with Happy Endings

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert

Survival Tips for Horse and Rider

- Preparing

an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms