5 Cryptic Icons of the Southwest

Mysterious and Mystical Native American Art

By Jay W. Sharp

Native American icons offer tantalizing clues to their world views, mysticism, cultural interchanges and mythology. The sheer diversity and number of images point to a complex and long-termed evolution of spiritual beliefs and rituals. Some, the plumed serpent, the outlined cross, the storm god, the Thunderbird, the hump-backed flute player and many others, reflect millennia-old threads of religious and philosophical beliefs that span the deserts of the Southwest, much of Mexico and even regions in South America. Here are five of the most mysterious and mystical icons found in the Southwest.

1) The Plumed Serpent

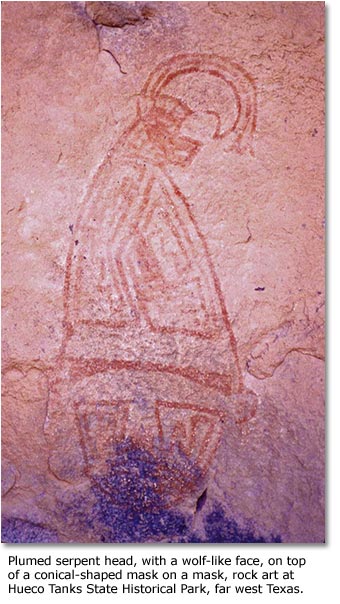

The plumed serpent, portrayed with a feathered crest and sometimes with either a wolf-like or a hooked nose, symbolized Quetzalcoatl, a deity who emerged among the great city states of Mesoamerica in southern Mexico and northern Central America some 2,000 years ago. His depictions, names, character, religious roles and spiritual associations evolved and changed among cultures and through time. In many incarnations, however, Quetzalcoatl was a benevolent god born of a virgin mother. He rescued humankind from the netherworld by dripping his blood onto the bones of men, women and children, giving them renewed life. According to the Aztec Gods & Goddesses Internet site, “He taught men science and the calendar and devised ceremonies. He discovered corn, and all good aspects of civilization. Quetzalcoatl is a perfect representation of saintliness.” Lord of hope, healing and the planet Venus, he glorified learning, arts, poetry and thought—“all things good and beautiful.”

Quetzalcoatl became “a god of such importance and power that nearly no aspect of everyday life seemed to go untouched by him.” Presided over by the planet Venus – the sacred evening and morning star – Quetzalcoatl’s priests beat their drums at twilight and dawn to separate daylight and darkness.

His plumed serpent symbol represents a visualization of the name, Quetzalcoatl, which combines the terms for the quetzal bird, a magnificently colored tropical species with three-foot-long tail feathers, and the coatl, the mythical serpent of storm clouds and lightning. His symbol and its derivatives, which appear on the rock art and ceramics of the prehistoric Southwestern desert, signify the extent of his spiritual reach outward from Mesoamerica. As it moved northward, his imprint varied with time, distance and cultural differences, apparently evolving from images of true plumed serpents to plumed and horned serpents to horned serpents (some with the horn pointing forwards over the head, others with the horn pointing backwards away from the head). As suggested by Dr. Kay Sutherland, an authority on Mesoamerican and Southwestern art, his image’s evolution from plumed to horned serpent may have represented his transformation from a deity of Mesoamerican city states to a deity of desert hunting peoples.

Quetzalcoatl, in symbolic form, still endures. In Mexico, for example, his image appears in department store windows at Christmastime, sometimes displacing the traditional Santa Claus figures.

2) The Outlined Cross

An outlined cross or, more accurately, an outlined “plus” sign, stood as perhaps the most common of many icons for Venus, the sacred body that the Mayans associated with Quetzalcoatl. It symbolized the religious importance of the planet and its eight-year cyclic passageway through the night sky. It spoke to Venus’ role in prophesy, human sacrifice and warfare.

“The planet Venus was particularly significant to the Maya. . . ” according to the Civilization Internet site. “The Dresden Codex, one of four surviving Maya chronicles, contains an extensive tabulation of the appearances of Venus, and was used to predict the future. The Maya also went to war by the sky. . . triggered by the planet Venus. Venus war regalia is seen on stelae and other carvings, and raids and captures were timed by appearances of Venus, particularly as an evening ‘star.’ Warfare related to the movements of Venus was, in fact, well established throughout Mesoamerica.

“Maya calendars, mythology and astrology were integrated into a single system of belief. The Maya observed the sky and calendars to predict solar and lunar eclipses, the cycles of the planet Venus, and the movements of the constellations. These occurrences were far more than mere mechanical movements of the heavens, and were believed to be the activities of gods replaying mythical events from the time of Creation.” Symbols of Venus embellish the facades of the monumental architecture of Mesoamerica.

While various prehistoric symbols of Venus radiate from Mesoamerica into Central America, South America and the desert Southwest, the outlined cross is the one that occurs most commonly, according to Domingo Sanchez, “The Mesoamerican Venus Symbol In Venezuelan Rock Art,” KACIKE: Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology. In the Southwest, it appears in prehistoric rock art and ceramics and even in modern Native American kachina masks.

3) The Storm God

The Mesoamerican storm god, a goggle-eyed snarling image often called “Tlaloc”, ruled the heavenly paradise of Tlacocan. He held command over rain, lightning and thunder as well as fertility. Although generally regarded as a benevolent deity, according to the All About History Internet site, he also instilled terror among the people. If angered, he inflicted destructive storms, hurled thunderous lightning bolts, and imposed disastrous drought. He demanded homage.

Especially revered among the Aztecs, Tlaloc ranked so highly that he warranted the construction of a temple in their ancient city of Tenochtitlan (within today’s Mexico City) and the elaborate decoration of his images at their monuments of the state. According to the Aztec Gods & Goddesses Internet site, he controlled access to Tlacocan, the heavenly paradise. He took pleasure, apparently, watching his priests plunge into frigid lake waters at the hour of midnight, thrashing and splashing like water birds until they grew exhausted. Tlaloc accepted homage in way of the sacrifice of human beings, especially children, whose tears he accepted as the price for delivering rain to the fields, the more tears the more rain. His priests tortured sacrificial children to induce more crying – and more tears, all reverently collected in ceremonial bowls – while parents took pride in their children who had been selected for the fatal honor.

In heavenly messages to the Aztecs, Tlaloc sent spring rains symbolized by the color gold from the east, signifying seasonal nourishment and renewed life. He sent summer rains marked by green from the south, reinforcing fertility. He sent fall rains, in the red of a sunset, from the west, signifying autumn and the retreating sun. He sent powerful winter thunderstorms from the north, bearing snow and hail that, according to Mesoamerican beliefs, embodied bones of the dead.

Tlaloc found his way, significantly modified, into the prehistoric and historic Native American peoples of the Southwestern deserts, where his control of rainfall and water would have held supreme importance. His images appear on the surfaces of prehistoric rocks and pottery. His goggle eyes and snarling mouth appear on the faces of prehistoric and modern kachina masks. Sometimes, only goggle eyes appear, presumably a kind of widely understood shorthand symbol for Tlaloc. He may have been a forerunner to the Kachinas, whose masks often feature goggle eyes and snarling mouths. He may still assert his presence in modern jewelry, clothing designs and paintings.

4) The Thunderbird

A monstrous, winged predator – labeled “Thunderbird” in the deserts of the Southwest and in other parts of the Americas – played stirring roles in the myths of peoples worldwide. It produced thunder from its wings and issued lightning from its beak. It raised and shaped landforms. It created mankind. It symbolized Native American “heaven.” It enforced ritual. It fed on men, women and children as well as large animals and even killer whales, littering the floor of its lair with the bones of its prey.

In the Sonoran Desert, a Thunderbird, which lived in a mountainous cave, preyed on the Pima Indians, according to a story in the True Authority Internet site. It died at the hands of Pima braves, who found the cave and blocked and fired the exit. The Thunderbird, roaring in a maddened anger, perished in the flames and smoke. Another Thunderbird died in a similar trap set by Pima Indians at a Puebloan village in southern Arizona. Still another fell to the arrows of a young Yaqui Indian boy, who had lost his entire family to the great predator.

In northeastern New Mexico, said Mark A. Hall in his book Thunderbirds: America’s Living Legends of Giant Birds, a Thunderbird stood guard over the Capulin volcanic crater. It died when attacked by an Indian warrior. In revenge, its spirit called the volcano to life, threatening to annihilate the warrior’s people. Appeased when the warrior’s brother sacrificed himself by leaping into the boiling lava, the Thunderbird returned the volcano to calm.

In far west Texas, on the western flanks of the Franklin Mountains, a Thunderbird survived attacks of Indians, who nevertheless managed to imprison it alive in its cave, according to Ken Hudnall and Connie Wang in their Spirits of the Border: the History and Mystery of El Paso del Norte. “Woe be unto him who frees the Thunderbird, for he will be responsible for death and destruction far beyond anything mankind has yet experienced.” On the western side of Thunderbird Peak, its presence is still marked, by a large red rhyolite formation shaped like a Thunderbird, “guarding the desert landscape, wings outstretched, head turned to the side, an immense, mythical silhouette. . . ”

The Thunderbird made its mark in Navajo mythology when it carried a warrior to a ledge at the top of the sacred Winged Rock (Ship Rock, located in northwestern New Mexico), said Hall. It appeared in Pueblo mythology as a great bird with “feathers like knives. . .”

The Thunderbird takes on many forms in the rock art of the Southwest, but it typically bears a resemblance to the bald eagle on the Great Seal of the United States of America.

5) The Humped Back Flute Player - Kokopelli

The humped back flute player, commonly known as “Kokopelli,” a Hopi Pueblo word, appears in various forms in rock art and ceramics from Peru northward to Utah, said Michael Claypool, an authority who taught at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. Classically, Kokopelli appeared as an arched-back man playing a long flute, but depending on his location, cultural affiliation and time, he may have taken on the guise of an elaborately costumed performer, a spare stick figure, a humped back rabbit, a flute-playing mountain sheep, an insect or numerous other forms. In some locations, he has a bird for a head.

A revered figure among the prehistoric Native Americans of the desert Southwest, Kokopelli played his flute for ceremonial dances. Sometimes appearing with just a hump, other times with just a flute, he took part in tribal rituals. He may have offered explanations for tribal myths. He petitioned the skies for rain. He invoked magic for hunting success. He impregnated women of the people. He helped deliver babies for the women. He led processions, perhaps migrations, of communities. He seems to have been charged with ensuring fertility for the people and their crops and good fortune in their undertakings. Occasionally, he appears in multiples, presumably redoubling chances for success.

Perhaps the most charismatic of the deities of the Southwest, Kokopelli appears today in ceramics, jewelry, metal arts, advertising campaigns, place mats, heating pads and even T-shirts and caps.

More Mythological Icons

In addition to Quetzalcoatl, the outlined cross, Tlaloc, the Thunderbird and Kokopelli, many other icons serve as important, and often poorly understood roles in the prehistory of the desert Southwest. Rock art bear tracks, for example, sometimes with elaborate decoration, other times with simple outlines, may have functioned as clan symbols or, possibly, territorial markers. Collared jaguars, controversial images distinguished by a tail folded over the back and a band around the neck, could indicate Mesoamerican origins or Puebloan clan roots. Black-tailed jackrabbit images recall Mesoamericans’ beliefs that they saw, not a man in the moon, but a rabbit in the moon. Images of macaws, tropical birds with parrot-like beaks and long tails, imply possible mercantile or religious relationships with Mesoamerican traders or missionary figures. Elaborately and precisely scribed geometric images point to sophisticated prehistoric designers. Complex mask images, apparently incorporating Mesoamerican design motifs, suggest connections with the great city states to the south.

Still other icons, dual figures, skeletons, animals, fish, mythical creatures, cloud formations, spirals, concentric circles, zigzag lines, and many others on stone and ceramic surfaces and ceremonial chamber walls, offer clear evidence of the overarching spiritual life of the prehistoric people of the Southwest.

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms