Navajo Rock Art & Pueblitos

Four Corners Holds Secrets of Navajo History

by George Oxford Miller

Some of the most dramatic art galleries in New Mexico aren't in Santa Fe, nor are their priceless masterpieces stored in hermetically sealed vaults for safekeeping. The petroglyph images on canyon-wall galleries near Farmington have been exposed to the blazing sun and torrential storms of the Southwest for 300 years. Yet, the centuries have not dimmed the life that seems to jump off the rocks at the viewer.

![]()

An hour's drive from Farmington on a web of dusty, unmarked roads takes us across a cottonwood-lined wash in Largo Canyon to the Crow Canyon Archeology Site. A cliff face of gleaming reddish-brown rocks borders a low mesa that rises to distant cliffs and blue sky. These scenic rocks and canyons hold the story of a little-known era in Navajo history.

"We're in the heart of Dinétah, the ancestral Navajo homeland from the 1500s to the late 1700s," Larry Baker, our guide and director of Salmon Ruins Museum tells us. "The Navajo left the area about 1770 and moved to their present location. The petroglyphs here are like stained glass windows in churches. The Navajos were saying, 'This is my land, my culture, my religion.' The images represent some of their earliest creation stories."

We walk along the promontory and round a corner to discover the Sistine Chapel of rock art. Panels of intricately carved figures and images stretch along the sheer wall. A life-sized corn stalk highlights one mural and realistic carvings of a warrior with a headdress and bow and arrows decorate another. We see drawings of bison and elk impaled with arrows, of birds, clan symbols, mysterious deities, and a set of concentric circles.

"On the equinox, the sun's shadow cuts through the center of the circles," Baker explains. He points to a beautifully carved warrior image. "The figure holding the bow and arrows with the headdress represents Monster Slayer, one of the Hero Twins at the time of creation. The monster's body became Mount Taylor and his blood the El Malpais lava flow." The western New Mexico mountain is sacred to the Navajo and forms the southeast boundary of Dinétah.

Baker doesn't claim to read the petroglyphs like pages in a book, but he does recognize the better known icons. "The hourglass symbol is a hair knot that represents the other Hero Twin, Born of Water." He points out squiggly, sperm-like figures that represent germinating corn, moccasin prints, turkey tracks, herons, dancers, and rows of stick figures that probably recorded the clans that lived in the canyon. The Navajos even chipped images of Spanish soldiers riding horses and swinging swords.

"We think this scene represents a battle that occurred here in 1705," Baker says. "The Pueblo Revolt in 1680 drove out all the Spanish. After the reconquest in 1692, the Spanish sent regular patrols throughout Indian country to establish that they were in charge."

As an archaeologist, Baker has spent his life studying and excavating the ancient ruins in the Four-Corners country. He is the chief archeologist at Salmon Ruins, an AD 1000 colony of the extensive civilization that developed at nearby Chaco Canyon. The San Juan Museum Association and Museum is headquartered at Salmon Ruins between Farmington and Bloomfield. Besides the excavated ruins, the grounds include a Heritage Park with examples of early village structures designed for a hands-own experience.

Baker also is a lead archaeologist in stabilizing the ruins of the pueblitos built by the Navajo who carved the intriguing rock art in the area. After a picnic lunch at the Crow Canyon site, we continue the tour to some of the most outstanding pubelitos in the area.

During the 1600s, Utes and Comanche regularly raided the Navajo to capture slaves to sell to the Spanish. By the 1690s, the Navajo began to leave their villages and build small fortified complexes, or pueblitos, perched on the edge of cliffs or other easily defended locations. The pueblito period lasted from about 1692 to 1750 when the Navajo abandoned Dinétah.

We leave the sinuous Largo Canyon and drive up onto the high desert mesa. In the distance we see Gobernado Knob, the center of the Navajo world where the deity Changing Woman appeared. Baker pulls over at the edge of an escarpment and we walk to a tiny pueblito on a high point overlooking the mesa below. The picturesque site would make a real estate agent drool.

We crowd into the one remaining room. Baker mixed polymers in the mortar when he stabilized the pueblito, but the roof is original. "Tree ring cores from the vegas indicate that Gould Pass Pueblito was built in 1741," Baker tells us. "Probably about twelve people lived here." A small door leads onto a sun porch, once another room, with a stunning view of the countryside and any raiding parties that might threaten.

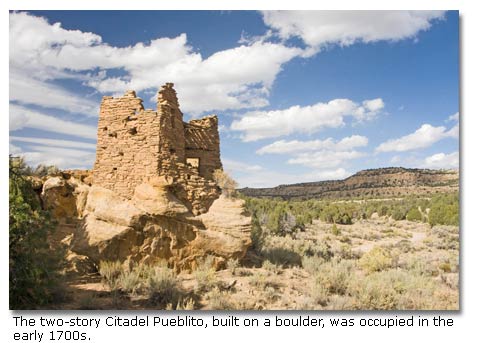

Next we visit the Citadel, an architecturally magnificent pueblito built on top of a huge boulder at the edge of a wash. The two-story, twin-tower complex even had a small courtyard. "They used a ladder to enter through that low door." Baker points out. "At night, they pulled up the ladder for safety."

It's easy to imagine adults tilling patches of corn, squash, and beans in the wash and the cry of playing children echoing across the pinyon-juniper hills. Yet without the dedication of Baker and other archaeologists, this and many other pueblitos would be just heaps of stone.

"Of the 217 pueblitos discovered, three-fourths have slid off their foundations," Baker says. "In 1997 I found photos of the Citadel taken in 1987. In ten years, ten feet of masonry had crumbled from one wall. We got a $20,000 grant from a gas company and saved the pueblito. At the Navajo's request, we used no modern materials, just the same mud mortar and stones the original builders used."

Seeing the Navajo rock art hidden in the recesses of sequestered canyons and the penthouse pueblitos with stunning views of the high desert adds a living dimension to this beautiful and mysterious landscape. Baker's infectious enthusiasm and knowledge helps us feel personally connected with the original inhabitants of the Four Corners.

If You Go

For tours of Dinétah rock art and pueblitos led by the Salmon Ruins Museum, see www.salmonruins.com (505-632-2013, sreducation@sisna.com) and click on the Guided Tours link. Tours are by arrangement only and cost $285 for up to people and include transportation and lunch.

For a Farmington area visitors guide with activities and lodging information, contact the Farmington Convention and Visitors Bureau, www.farmingtonnm.org, 800-448-1240, fmncvb@earthlink.net.

Click here for more about the Navajo.

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Your GPS Navigation Systems

May Get You Killed

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Desert Survival Skills

- Successful Search & Rescue Missions with Happy Endings

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert

Survival Tips for Horse and Rider

- Preparing

an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms