Old Time Drugstores

Pharmacists in the Desert

Joe Zentner

Because health has always been a primary concern to people, it is not surprising that the profession of pharmacy – the preparation and dispensing of therapeutic agents – is mentioned in early records of civilization. Around 2000 BC, for example, pharmaceutical information inscribed on long scrolls and clay tablets was inspected by the peoples of Egypt and Babylon.

We know from these sources that the “pharmacists” of those ancient times used many common materials – for example, minerals, oils, seeds, herbs, leaves and roots – as “medicines.” A few of those ancient remedies have survived the test of time.

In the 1730’s, nearly half a century before the Constitution of the United States was framed, Dr. John Frederick Otto and Dr. John Adolph Meyer established “Die Apotheke” in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. It was America’s first drugstore.

In 1764, then–patriot Benedict Arnold operated an apothecary shop in New Haven, Connecticut. Today, in the building that houses the New Haven Colony Historical Society, there is a large black sign that bears the inscription:

B. ARNOLD, DRUGGIST

BOOKSELLERS &C---

FROM LONDON

SIBI TOTIQUE

Beneath the sign there is a mortar and pestle as well as a medicine chest from “Arnold’s Apothecary Shop.”

Another early pharmacy was the Poulnot Drug Store, located on King Street in Charleston, South Carolina. It was established in 1781 with Dr. Andrew Turnbull dispensing various remedies. The shop’s name was changed to Apothecaries Hall after Dr. Jacob De La Motta purchased it in 1816. Still later, a golden mortar sign was placed over the entrance that carried the inscription The Big Gilt Mortar.

Before legislation was enacted to regulate druggists, many enterprising individuals combined a pharmacy practice with other trades. These included surgeons, ministers, schoolmasters, lawyers, butchers, millers and even poets. In a botanical garden enclosed behind the shop were grown the herbs, roots and other medicinal plants from which drug remedies were compounded. In a typical garden grew jimsonweed (from the archaic Jamestown weed—named for Jamestown, Virginia), prickly ash, red oak, deer tongue, lavender, ginger, thyme, berries, and many other herbs and plants.

Today, visitors to several drugstore museums in the southwestern United States can take a trip back into medical history, to a time when druggists dispensed leeches to patients as a means of allegedly drawing out sickness through “blood letting.” (Adolf Hitler was fond of leeches.) Inside these museums, a bit of medical history is re-created in early apothecary shops.

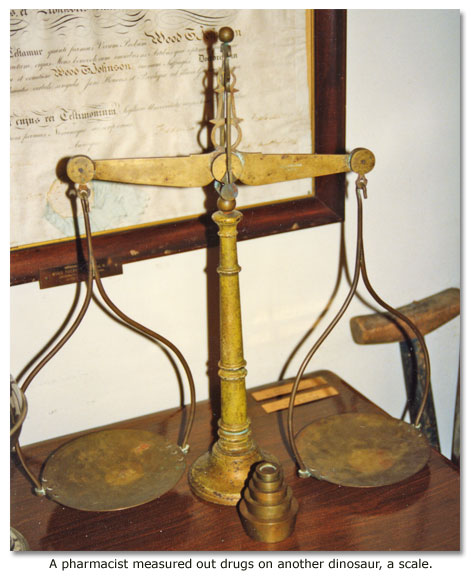

Typically, the museums exhibit the tools, medicines and furnishings of a typical desert drugstore when the profession was in its infancy. Mostly there are medicines—row upon row of glass jars labeled with tongue-twisting names. They contain ingredients that the pharmacist mixed as well as bottles of manufactured “remedies,” containing concoctions of questionable therapeutic value, though alcohol was a universal ingredient. (At age 22, while teaching college in Louisiana, I met Dudley LeBlanc, “father” of a legendary early 20th century proprietary medicine called “Hadacol,” which had an alcohol content of 35 percent, or seven times that of a typical beer.)

One “remedy,” labeled “Neoferrum,” was used to treat anemia due to iron deficiency. It was billed as “an appetizing hematinic [acting to improve the blood] tonic,” whatever that means. Neoferrum was undoubtedly appetizing, in that one of the primary ingredients listed on the label was sherry wine.

Also on display in some drugstore museums is Ferri-Tone, which claimed to cure “indigestion, loss of manhood, general debility and depraved conditions of the system.” Another “medicine” of the late 19th century, which can be seen in some pharmaceutical museums, was prescribed to heal “diseases of indiscretion in young men.” Some of the “miracle” cures specialized in “female problems.” Others were equally good “for man or beast.”

Early desert drugstores did much of their business in proprietary “medicinals,” many with untaxed 10 to 50 percent alcohol content. Indeed, most patent medicines were composed primarily of alcohol and a few harmless ingredients. Doctor Ezekiel’s Heart Treatment, for example, contained alcohol and tomato paste.

Few if any such “medicines” could live up to the extravagant claims that their manufacturers made, and many disappeared from the scene after 1906, when newly-enacted federal government regulations required that the word “cure” be removed from the labels of unproven formulas.

The 19th century pharmacist also provided legitimate natural products, including herbs, roots and willow tree bark (from which aspirin is derived); a number of these are displayed in pharmacy museums. You can, for example, view digitalis, made from the dried leaves of the foxglove plant, which was and still is used to treat coronary disease.

In addition to an extensive collection of original patent medicines, pharmacy museums in the southwest also display an ominous array of medical paraphernalia, including “scarificators,” “tonsil guillotines” and an ordinary corkscrew.

A “scarificator” was a tool physicians used to relieve patients of “bad blood,” that is, blood which supposedly contained impurities. With one flick of the wrist, 12 sharp blades emerged to inflict wounds on a compliant (although likely terrified) patient.

The tonsil guillotine features a long-handled cup, on which tonsils were somehow situated. A blade was then released, guillotine-style, to sever infected tissue from the back of the throat. It is difficult to imagine what that must have felt like.

The corkscrew was used to bore into the brain to relieve pressure. The idea may have been borrowed from an early southwestern Apache instrument used for this purpose.

To the student of medical and pharmaceutical history, old apothecary shops hold an enduring interest; laypersons also find them fascinating. Visitors come away delighted and sometimes awed by what they have seen. Most are grateful for centuries of therapeutic progress. But one has to ask: “Has there really been that much progress made in what people are likely to swallow, metaphorically, if not physically, when their health is, supposedly, at stake?”

A cursory review of the drugs being hawked relentlessly on television today for this or that affliction causes some people to wonder if Americans are not today, as in times past, addicted to pills and potions and devices that may not really solve the age-old problems of human existence.

Herbal Medicine of the American Southwest Book

Some Pharmacy Museums

- Historical Drug Store Museum, 12 miles north of Ely, Nevada, on Highway 93 in the tiny town of McGill

- Donald Salvatori California Pharmacy Museum at 1112 I Street, Sacramento

- Oklahoma Frontier Drug Store Museum at 214 West Oklahoma Street, Guthrie

- History of Pharmacy Museum, University of Arizona’s College of Pharmacy campus, Tucson

- Heritage Society Pharmacy Museum at 125 East Main Street in the small town of Weimar, Texas, off Interstate 10, between San Antonio and Houston

Related DesertUSA Pages

Idiosyncratic Desert Museums

General Patton Museum

People & Cultures of the Southwest - Index of Articles

Telegraphy, Desert Saloons & Sport Gambling

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms