Desert Saloons and Sport Gambling

The Wild West

by Joe Zentner

The results of organized sporting activities have long intrigued people, especially when money spent on betting on those results is involved. How to get those results quickly to people widely scattered around the American Wild West presented a real challenge. Money wagered is more than likely money lost, unless sports results can be quickly confirmed. Science, and before that, nature, sought to respond to the challenge, with mixed results.

Telegraphy (from the Greek words tele, meaning far, and graphein, meaning to write), involves the long-distance transmission of written messages without physical transport of letters. The first “telegraphs” were optical messages, including the use of smoke signals and beacons. These forms of communication have existed since ancient times.

A smoke signal is a form of visual communication developed both in the American West and in China. By covering an open fire with a blanket and then quickly removing it, a puff of smoke can be generated. With some training, the sizes, shapes, and timing of these puffs can be controlled. Puffs may be observed from fairly long distances, apparent to anyone within visual range. What messages were transmitted? Possibly they told of the location of game, abundant desert cacti, which oftentimes meant edible fruit, or imminent enemy attacks.

Signaling stations were sometimes created to maximize the viewable distance. Stone platforms used by Native Americans and the towers of the Great Wall of China are examples of signaling stations.

There is no standardized code for smoke signals; the signals are often of a predetermined pattern discerned mainly by sender and receiver. Consequently, smoke signals tend to convey simple messages, and are, therefore, a limited form of communication. It is doubtful that what happened, sporting-wise, in, say Chicago or St. Louis, could have been transmitted effectively by smoke signal.

What to do? Historians of technology are cautious about naming the first person to invent anything. Why? Because someone else invariably shows up having thought of the idea first. The telegraph is no exception.

The noted American painter Samuel F. B. Morse did put together a telegraph system in 1837. However, it was probably his invention of an early version of what we call the “Morse code” that got him credited with having invented the telegraph.

The seed for the telegraph was sown 90 years earlier, in 1747, when the Englishman William Watson showed that electrostatically generated signals could be sent a long way through a wire with the circuit being completed through the earth. In 1753, an anonymous writer published a magazine article showing how it was possible to use an array of 26 such wires – one for each letter of the alphabet – to send messages over long distances. The notion of sending all the letters on a single wire – of using a code to distinguish them – was introduced in 1774 by a French inventor named Henri Lesage.

In telegraphy, an electric circuit is set up using a single overhead wire and employing the earth as the other conductor to complete the circuit. An electromagnet in the receiver is activated by alternately making and breaking the circuit. Reception by sound, with Morse code signals received as audible clicks, is a swift and reliable method of signaling.

Western Union

It was a short, even telegraphic message: “Effective January 27, 2006, Western Union will discontinue all Telegram and Commercial Messaging Services. We regret any inconvenience this may cause, and we thank you for your loyal patronage.” With those words, Western Union announced the death of the telegram, the original form of electronic communication.

The Western Union Telegraph Company was created in 1851 to provide telegraphic communication services in the U. S. Originally known as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company, Western Union built the nation’s first transcontinental telegraph line in 1861. The company briefly entered the telephone field but, after losing a court battle with Bell Telephone in 1879, turned completely to telegraph communications.

The technology certainly had a long run. Officially, the first telegram sent in the United States was “WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT?” Samuel Morse transmitted it May 24, 1844, along the experimental telegraph line he had constructed between Washington, DC and Baltimore.

At the time, Morse was thought to be deranged, and his scheme to send messages along wires was widely assumed to be some sort of scam. When the line between the two cities opened for business in 1845, it took in one cent of revenue in its first four days of operation.

But the technology soon took off. By 1852, the United States had the most extensive telegraph network in the world. The lines hummed with telegrams whizzing to and fro. Dozens of competing companies sprang up to build and operate networks; in 1856, several of them merged to form Western Union. The company went on to establish a near-monopoly of the industry.

At the height of the telegraph mania, the seeds of its eventual destruction were sown with the invention of the telephone in 1876. At first, the “speaking telegraph” (as it was known) was merely expected to speed up the transmission of telegrams by enabling telegraph operators to dictate messages to each other, rather than tapping them out in Morse code. But the telephone’s effect was far wider, because, unlike telegraph equipment, anyone could use it. It obviously made sense to install direct telephone lines into homes and offices.

That said, early telephones could be used only over short distances, and even when long-distance calling became technically possible, it was frightfully expensive. Consequently, telegrams reached the height of their popularity in the 1920s and 1930s before falling into a long, slow decline that ended with the final telegram sent in January of 2006.

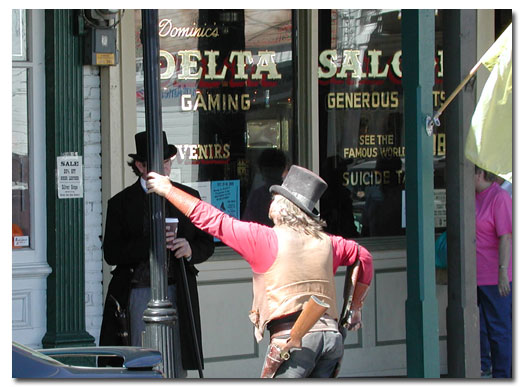

Desert Saloons

In frontier days, saloons sprang up everywhere, attracting men of all stripes, including gunslingers, cattlemen, prospectors, miners, gamblers, and politicians. Cattle, land, gold and girls were traded while sipping, slurping, or throwing back “red eye” (typical ingredients included red ink, red peppers, black chewing tobacco, Jamaica ginger, molasses, “Hostetter’s Bitters” and painkillers). Saloons were places to sit back, relax and rinse dust out of the throats of an assortment of characters with various amber-colored liquids.

Gambling and the Wild West

The frontier lifestyle and gambling shared similar foundations—a spirit of adventure, opportunity and much risk taking. As the country moved westward after the Civil War, the frontier spirit spread.

Mining booms increased the rush to the West. Miners, lured by promises of easy and abundant riches, personified the frontier spirit. Mining was a gamble, and risk-taking was valued, because it represented an opportunity to achieve great wealth. In general, gambling and the Wild West were intimately linked. Gambling was especially widespread in mining camps.

As towns sprouted in the 19th-century American West – outside Army forts, at river crossings along wagon trails, in mining districts and at railheads – some of the first structures built were recreational facilities. “Recreation” for the almost totally male population in these towns inevitably meant the triple-W vices of the frontier: whiskey drinking, whoring and wagering. Saloons, brothels and gambling halls appeared almost overnight.

Telegraphing Sports Results

Two sports and five electronic manufacturers/communication companies dominated early mass broadcasting in the U. S. The sports were professional baseball and prize fighting. The five companies were Westinghouse, General Electric, Western Union, American Telephone and Telegraph and the Radio Corporation of America.

Early communications technology did not allow for live broadcasting from the actual site of an athletic event. Instead, radio station operators had to rely on reports of outcomes to be telegraphed to them after the conclusion of an event.

Boxing, Gambling and Telegraphy

In the mid-19th century, St. Louis, New Orleans, Detroit and other cities far removed from the East Coast became centers of boxing in America because the eastern cities enforced laws against prize fighting. Interest in the outcome of boxing contests piqued the interest of men who hung around saloons where gambling was actively pursued in the desert Southwest.

One noteworthy early bout was the Jim Corbett-Jim Jeffries fight on November 5, 1900, a match won by Jeffries on a knockout in the 23rd round. Jack Root, a former light heavyweight boxing champ, owned a theater in Chicago. During the fight, a telegraph operator sat on stage, transmitting an account of what transpired. Root charged admission to the fight—making this the First Pay Per View (more accurately, the First Pay Per Hear) boxing contest.

Early in the 20th century, the United States became the center for professional boxing. Boxing enthusiasts generally accepted that the “world champions” were those listed by the Police Gazette. After 1920, the National Boxing Association began to sanction “title fights.” Also about that same time, Ring Magazine was founded and began awarding championship belts. Little of this was lost on men in desert saloons who were downing “red eye” or whatever, while casting amorous glances at the relatively few females who hung around such places.

Radio station WWJ, in Detroit, is considered by historians to be the groundbreaker in bringing sport results quickly to the American public. Announcers from the station reported the results of the Jack Dempsey-Billy Miske heavyweight title fight in September of 1920. Those results, before long, found their way to bars in Tombstone, Yuma and wherever else gamblers congregated.

Outcomes of sporting contests have long fascinated people, especially when money rides on the results of those contests. Persons who hung out in early desert saloons, while far removed from the physical action, nonetheless cared deeply about their outcomes, especially when they had bet their hard (or easily) won dollars on the consequences.

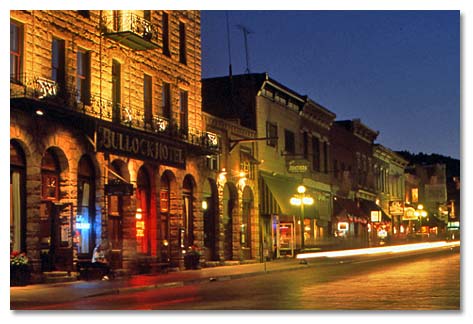

While viewed as a primitive (read defunct) form of communication today, telegraphy in Wild West days was, technologically speaking, state of the art and contributed significantly to binding disparate regions of the country together. Gambling may or may not be a vice, but it has certainly made an important contribution to making life more interesting, whether it be in Prescott or Tombstone, Arizona; Deadwood, South Dakota; Dodge City, Kansas; or Laughlin, Nevada.

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms