World Deserts Sand Dunes

Rhythms Of Shifting Sands

Text and Photos by Carol Polich

It was not in the American Southwest, but in southern Africa's desert country of Namibia, where I discovered the magic in the solitude, the tranquillity, the silence within towering dunes of soft and undulating desert sands. I savored ephemeral moments that could be broken by the sound of footsteps on a desert floor 200 meters away. Back in the United States, I found, in a continuing voyage of discovery, the spiritual connection between the pastel dunes of Namibia’s Namib desert, the golden dunes of Death Valley, California, and the white gypsum dunes of White Sands National Monument in New Mexico.

All these dune fields lie within desert basins surrounded by mountains. They are desolate, with a quiescent and haunting beauty. Equipped with camera, water, sunscreen and brimmed hat, I have explored these dunes, searching out the ever changing rhythmic patterns and contours, hoping to capture a meaningful and moving photograph. I have learned that dunes are best photographed and experienced in the two hours after dawn or before dusk, when the rising or lowering sun warms the colors and shadows define the sand dunes’ graceful shapes. Late morning through mid-afternoon is the time to avoid the dunes, when they are at their worst because of the white-hot sun.

The Namib Dunes

The Namib dunes, along the western edge of Namibia, have been contoured and shaped into mini-mountains 900 feet high. The desert floor is covered with polished quartz pebbles and large granite rocks, which are awash in blowing quartz-grain sands. Early in the morning, before my eyes, the Namib dunes shift in colors, ranging from coral, mauve, magenta and pink to blue and gold hues, providing a striking contrast in the shadowless sands of midday, when the Namib’s sands can blister bare feet.

A phenomenon unique to the Namib is the morning fog which drifts in from the Atlantic ocean. It is created when the warm desert air converges with moist cold air blowing inland from the ocean, dropping temperatures low enough to warrant sweatpants and a long sleeve shirt. Footprints left in the sand are edged in moisture. Dew collects in droplets not only on grasses but even on fingernails. Humidity and cold seep through clothing and chill the body before the sun’s warmth finally drives away the fog, which may extend inland as far as 35 to 40 miles.

Hiking a dune’s leeward side, or "slip face," which slants at angles of 32 to 34 degrees, is great for getting in shape but bad for carrying photographic equipment. The slip face is one of constantly cascading sands at its steepest angle. The other side, the "dune slope," lies at an angle of 14 degrees. Sun, wind and water cause constant change in textures and patterns of the dunes and valley floors. Patterns reaching from the foreground to the distant dunes look like outstretched fingers. At the top of a dune, I make pictures, and I study the vast dune sea, following soft linear and curving lines, watching the interplay of shadow and light.

As I hike further, the desert scenery becomes more complex and assumes a different sort of beauty. Vegetation survives somehow within the arid conditions. Golden grasses stand tall, forming patterns and shadows in the sands. Shrubs offer gnarled and thorny branches to browsing animals. Camel thorn trees, with rough, dry bark, provide not only shade for the weary hiker, but also a type of pod which supplies nourishment for the gemsbok (oryx).

The oryx is the largest of the antelope species living in the Namib dune field. With its sabre-like horns, this magnificent gray, black and white creature shares its habitat with me. Unlike me, an oryx usually knows exactly where he is going whether in search of a small water hole or a moisture-filled tsamma melon (which often fulfills his water needs). Oryx also eat the edible fruit of the dry and thorny green nara plant. Tracks left by oryx, springbok, ostrich or desert jackals cross dune slopes and gradually disappear over distant dunes.

The many dried "pans" between dunes recall an oasis of life which survived for years, and they offer a sharp contrast in patterns and colors. Trees once lived within the pan, but now they stand naked and barren, giving a feeling of the macabre. The mud on the pan floor hardened and cracked as the water evaporated under harsh desert winds and searing sun. On the edge of the dried and caked mud pans are fluid and snake-like rippling patterns of sand. These patterns extend outwards to other geometric patterns in the dry lake bed. Pug marks in the mud have turned to hardened spoor in the sun-baked clay.

The Death Valley Dunes

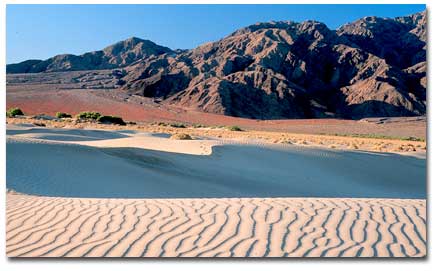

A new journey would take me to the smaller, beach-colored, mesquite dune fields in Death Valley National Park in southern California. There, I wander on the hard and pebbled ground between the creosote and mesquites, pale green bushes sustained by shallow ground water.

Active primarily during the cooler hours of early mornings and late afternoon and evening, coyotes (the largest of the Death Valley predators), the kit fox, beetles, the sidewinder and kangaroo rats represent only a few of the creatures who leave their spoor.

By 9:00 a.m., when the dunes begin to heat up, this area teems with lizards. The most common is the Desert Iguana, a whitish-gray, 12- to 14-inch long reptile, speckled in red and black spots. I stalk these reptiles with my camera.

Entering the dunes early, you realize that they are "solitary" and "desolate" only within our minds. The multitude of tracks left a few hours previously suggest the variety of life which survives in this "barren wasteland."

The Death Valley dunes are surrounded by dark, rocky mountain ranges: the Cottonwoods to the west, the Grapevines to the east, and Tucki Mountain (a part of the Panamint Range) to the south. Weathered by wind and rain, the Cottonwoods, the primary range, parent the sands by yielding particles of magnetite, quartz and other minerals. The dunes cover a 15-square-mile area and rise to only 80 feet, small compared to the Namib dunes.

Although they have the qualities of quietness and solitude, they have their own distinctive features and colors. At low light, the hues range from golds to blues, with sinuous patterns curving along the loose sands. Some patterns, in tightly knit weaves, mesmerize you. The blackened shadows cast against the golden sands give a sense of dark chasms.

The dry pans, called "playas" (or "beach"), a Spanish word reflecting the earliest European colonizers of California, expose the surface upon which the dunes rest. This playa is an old clay lake bed. Because of the clay, rain water pools as if trapped by a saucer. Large geometric patterns form while the burning sun dries the moisture. Thin edges of dried mud curl upward and peel away from the giant playa like dried skin peeling from a sun burned back.

The evening light not only casts its glow upon the sands, it also enriches the Grapevine Mountains with mauve, magenta and dull purple colors. These craggy mountains contrast sharply with the smooth sculpted contours of the rhythms of the sands.

The White Sands Dunes

A two days' drive east of Death Valley, through Arizona and into New Mexico, takes me past the area where missiles are fired and weaponry tested by the U. S. military – the White Sands Missile Range, which seasons my next adventure in sand dunes, specifically, those of the White Sands National Monument.

I am struck by the contrast of the monument’s white sands compared with the coral-colored sands of the Namib and the tan- to gold-colored sands of the Mesquite dunes in Death Valley. White Sands is located in the northern reaches of the Chihuahuan Desert, in the south central part of New Mexico. Over 250 million years ago, the gypsum which comprises the white dunes was deposited by a shallow sea. Eventually, a stone dome formed with the uplift of the Rocky Mountains. The gypsum was trapped within the dome. Over 10 million years ago, the dome began to collapse, creating the Tularosa Basin, the location of the White Sands National Monument. The basin lies between two mountain ranges, the San Andres to the west and the Sacramentos to the east, the remnants of the original dome. Gypsum, a hydrous form of calcium sulfate, is water soluble. Rain and snowmelt dissolve the gypsum from rocks, carrying it from the San Andres Range into the Tularosa Basin – a continual supply of the mineral for dune formation.

Coming from the northern state of Montana, where we have snow-covered ground seven months out of the year, I felt at home in the whiteness of these dune fields, except that I now felt searing heat instead of frigid cold. The hues from the low light upon these dunes range from shades of pink and blue to light purples. The gypsum would not scorch bare feet as quickly as the Namib sands. Being of finer material than the quartzlike sand in Namibia and Death Valley, the White Sands dunes does not hold sharply defined cornices at their crest, and they do not form rhythmic patterns as distinctively on dune slope sides.

The White Sands playa floors, referred to as "interdunal flats," are covered with selenite crystalline deposits rather than mud patterns. Selenite is a crystal form of gypsum. Low bunch grasses, characteristic of the desert, grow on the playas.

Contrasting with the whiteness of the dunes are a number of colorful plants. These include, for instance, the golden to green rapier-like leaves of soaptree yucca, which grow in linear opposition to the surrounding curves of the dunes. This plant, growing as much as a foot per year, extends its stem to keep its leaves above the drifting sand.

Fuchsia-colored sand verbena flowers live in small clumps within the patterned desert floor. The brightness of this beautiful flower, perennial because of shallow subsurface moisture, gives warmth to the bleached sand dunes.

Hairy skunkbush sumac caps huge pedestal formations, binding gypsum grains around their roots. Once a gypsum cast hardens, remaining loose granules blow away, forming an indentation around the base of the pedestals, giving the formations their distinctive form.

As the heat rises, I search the grasses within the playas for the well camouflaged bleached earless lizard. He is as white as the sands. These reptiles lack external ear openings, but they are not deaf. Hovering beneath the yucca leaves or flattened out on the sands, they are quick and so well camouflaged that it takes a sharp eye to spot them.

Camping within the dunes is in itself an adventure into solitude. Be prepared to trek over the sands for more than a mile, depending on which site you have been assigned. The nearest person will be located beyond the next one or two dunes. There are only 10 camp sites, so you can experience a unique, isolated wilderness setting under an astonishingly starry sky. A quarter moon will provide enough light to cast your shadow on the dune floor. Since the park opens and closes at sunrise and sunset, it is unlikely that anyone will disturb you.

I got up early in the morning so that I could capitalize on the best light for photography. Searching for patterns in the sand, I knew I would be challenged.

Lessons Learned

In any desert, the dry winds, intense heat, deep sand and little shade can easily sap a person's strength and will. Learn from the bleached bones you pass on the way in search of the rhythmic and timeless sands.

Related DesertUSA Pages

Photography

Death Valley National Park

White Sands NM

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms