Cave Creek Canyon

Arizona

I could hear the call of a whippoorwill from somewhere out there in the darkness, the only sound other than occasional sighs of wind that moved slowly down the canyon in the night like restless spirits, stirring the leaves of the Arizona sycamore and Freemont cottonwood trees. Overhead, I could see the constellations of the stars and follow the arcing paths of the planets, brilliant points of light set against a sky of velvety blackness. At such times, I can understand the mysticism and vision quests of the prehistoric shamans and medicine men.

My wife, Martha, and I, with our youngest son, Mike, our daughter-in-law, Terry, our grandson, Adam, and our cocker spaniel, Pokey, had come to Cave Creek Canyon, on the eastern flanks of the Chiricahua Mountains of southeastern Arizona to learn about an area new to us. In earlier years, we had camped in the Gila Wilderness, to the northeast, and in Mexico’s Sierra Madre range, to the south. We had driven past the Chiricahua Mountains – a part of the Coronado National Forest – on various occasions. We had even visited the historic Fort Bowie, in the northern end of the range, but we had never really paused to explore any part of the area.

Across A Historic Land

To get to Cave Creek Canyon, we had driven westward, along the northern edge of New Mexico’s bootheel country, a region of desert basins and mountain ranges as remote and alien to most people as the surface of Mars. Following State Highway No. 9, we paused briefly at Columbus, where Pancho Villa and his guerillas attacked the border hamlet and a U. S. military encampment on March 9, 1916, during the Mexican Revolution. We crossed the Playas Valley, through which Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke led his 397-man Mormon Battalion in 1846 on a 2000-mile march to California, intending to fight in the Mexican/American War. We crossed the Animas Valley, which the Chiricahua Apaches used during the 1880s as an escape route into Chihuahua and the Sierra Madre when they bolted the hated San Carlos Reservation in east central Arizona. Approaching the state border, we passed just a few miles north of Skull Canyon, not far from Skeleton Canyon, where Geronimo and his destitute and dispirited Chiricahua followers surrendered to the insufferably arrogant U. S. Army General Nelson A. Miles on September 4, 1886, bringing an end to centuries of conflict between the Indian peoples of the land and the European descendants of the United States. We intersected U. S. Highway 80 near the Arizona and New Mexico border, turned south for four miles, then west on the road to the hamlet of Portal, at the mouth Cave Creek Canyon and the Chiricahua Mountains. This is the entrance to what was once the homeland of the great Chiricahua chief, Cochise, and his Chonoken band.

As we drove into the Y-shaped canyon, with its South Fork and North Fork, we passed between towering, lichen-covered and sculpted edifices of stone that recalled the time of a more violent earth. We could see the numerous caves that gave the canyon its name. We would see that the plant and animal communities of the dry sands of Chihuahuan Desert gave way swiftly to the vegetation and wildlife of the higher elevations and a mountain stream.

Cave Creek Visitorss Information Center. USDA Photo

Violent Origins

The Chiricahua Mountain range, the largest in southern Arizona, emerged from the basin floor some 27 million years ago, the product of a volcanic convulsion that blew 100 cubic miles of molten rock and ash into the sky, according to Jonathan Hanson in the online magazine Outside Online. The volume of material eclipsed that ejected by Mount St. Helens in its eruption in 1980 by 1000 times, according to the National Park Service. The eruption, said the NPS, “eventually laid down two thousand feet of highly siliceous ash and pumice. This mixture fused into a rock called rhyolitic tuff...” The restless earth fractured, lifted and rearranged the rock mass into tilted or vertical blocks, “...and eventually [the tuff formation] eroded into the spires and unusual rock formations of today.” Now, the Chiricahua Mountain range covers some 1000 square miles. It towers more than a mile above the desert basin floor and nearly two miles above sea level. Like other Southwest mountain ranges that are isolated by surrounding desert basin “seas,” the Chiricahuas have been called a “sky island” by biologists.

Life at the Crossroads

At the end of the Ice Ages, about 10,000 years ago, the Chiricahua Mountain range gave rise to a rich biological stew of plant and wildlife communities, stirring in ingredients from the Chihuahuan Desert to the east, the Sonoran Desert to the west, the Rocky Mountains to the north, and the Sierra Madre to the south.

Its lower flanks support desert scrub and grasslands, with a mix of mesquites, creosote, acacia, yuccas, agaves, barrell cactus, prickly pear cactus, hedgehog cactus, various grasses and other plants that are drawn from the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts. Its higher elevations host oaks, juniper, sycamores, walnuts, maples, willows, pines, fir, spruce, aspen and others that have botanical kin in the Rockies and the Sierra Madre. Bare stone walls and columns stand cloaked with yellow-green lichen (interdependent algae and fungus), looking as though paint had been spilled down their surfaces.

The range serves as home to one of the most varied wildlife populations in the United States, a reflection of the differing environments between the desert foothills and the high forestlands. Its mammal community, for instance, comprises some 80 different species, including creatures as small as the desert shrew (three inches in length), as large as the black bear (six feet in length), as storied as bats (some two dozen species in all), as common as the cottontail rabbit (a gourmet food source for the larger predators), and as unusual as the jaguar or the jaguarundi or the ocelot (rarely seen visitors from Mexico’s Sierra Madre). The range’s bird community consists of nearly 400 species—a national treasure trove. It includes those as bejeweled and small as small as the hummers, as majestic and large as the bald and golden eagles, as drab as the brown-headed cowbird, as brilliant as the summer tanager, as common as Mexican jays, and as rare as the eared trogon.

The range, in its biological diversity and richness, has also held a long attraction for man, including early nomadic bands, who carried stone-tipped spears and hunted the big game of the Ice Ages; far-ranging hunters and gatherers, who turned increasingly to plants for food as the Ice Ages ended and the big game species died out; village farmers, who raised corn, made pottery and adapted the bow and arrow; and, finally, the Chiricahua Apaches, who became the fiercest of guerilla raiders on the American frontier.

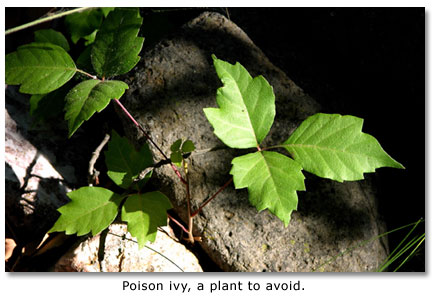

While the entire range ranks as a natural wonderland, it is Cave Creek Canyon that stands out as the crown jewel, primarily because of its running stream, an exceptional feature in the arid Southwest. Cave Creek nourishes an abundance of vegetation such as sycamore, cottonwood, oak, juniper, cypress, pine and grape. (It also supports fine stands of poison ivy, which can ruin your whole day if you’re allergic to the plant and you’re not careful to avoid contact with it.) The riparian environment, in turn, attracts an abundance of wildlife. Cave Creek Canyon offers so much, in fact, that the American Museum of Natural History’s Center for Biodiversity and Conservation has operated a research center for students, geologists, biologists and anthropologists in the North Fork for half a century.

Birds, Birds, Birds

The stones, plants, wildlife and archaeological remains attract students and scientists to come to Cave Creek Canyon to study in fields with exotic-sounding names such as arachnology, entomology, herpetology, ornithology, mammalogy, botany, geology, anthropology and ecology, but it is the bird population, in particular, that stands as an irresistible lure to an international cadre of knowledgeable enthusiasts.

According to Richard Cachor Taylor’s Location Checklist to the Birds of the Chiricahua Mountains, “...the Chiricahua checklist presently stands at 375 species, not including 13 species still considered hypothetical—about half of all the birds regularly occurring on this continent north of Mexico.” The desert scrub and grasslands provide homes for birds such as the Gambel’s quail, the cactus wren, the verdin and the curve-billed thrasher—residents of both the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts. The forested slopes serve up accommodations for species as diverse as the western screech-owl, the Virginia warbler, Scott’s oriole, the hairy woodpecker, the sulpher-bellied flycatcher, the zone-tailed hawk, the pygmy nuthatch and the greater pewee. The mountain crests call to the golden-crowned kinglet, the red crossbill and the golden eagle.

Cave Creek Canyon’s South Fork serves as the Chiricahua’s primary summer home for the species that many regard as the Holy Grail of birding—the elegant trogon, called “surpassingly beautiful,” by the GORP Internet Site. “It is, after all, a relative of the quetzal, the bird revered by Mayan priests.” The male elegant trogon, about 12 inches in length, sports an emerald green back and throat, a brilliant red breast and a yellow beak. The female has a brown body, a pink lower belly and a white eye ring. The trogons nest in cavities in trees, usually in dead or dying sycamores. They feed on insects and fruits in the forest canopy, especially among the sycamores. The elegant trogon issues a distinctively inelegant cry, which the GORP site describes as a combination of the “call of a hen turkey with both a pig’s grunt and a dog’s bark...”

Since only about two dozen of the birds appear in the canyon each summer, the elegant trogon can cause the enthusiast’s pulse to beat faster. Hearing the bird’s raspy call during a camping trip to Cave Creek Canyon, Christina Nealson said on her website, Mexico Notes: One & Two, “I grab my binoculars and take off running towards the croaky voice, crossing a dry arroyo towards a grove of...white-barked sycamore trees. Closer. Closer. He calls again. I stoop and crane my neck to see through branches. There he is! Scarlet and iridescent green... He calls and calls. I stand, mesmerized... We are a pair.”

We missed seeing the elegant trogon during our first visit to Cave Creek Canyon, but we’ll be going back, listening for a call that sounds like something issued by a surpassingly beautiful biological cross of a turkey, a pig and a dog.

Going There

You can visit Cave Creek Canyon any time of year, although you may run into snow in the higher elevations during the winter. You will find that late spring and early summer months have the highest populations of birds. Summer calls the wild flowers into bloom. Autumn summons the trees to change their colors.

To reach Cave Creek Canyon, you can turn south on U. S. Highway 80, off Interstate Highway 10, at the village of Roadforks, a few miles east of the New Mexico and Arizona border. After a drive of about 27 miles, you will come to the intersection with Portal Road, or State Road 533, which you will follow west for some seven miles to Portal and another mile or so to the Cave Creek Canyon Visitor Center, a good place to get oriented. It also has a display of snakes, including a particularly surly Mohave rattlesnake.

Map NFS

The U. S. Forest Service maintains several campsites within the canyon, including some with trailer spaces, restrooms, tables and drinking water. Call the Douglas, Arizona, Ranger District (1-520-364-3468) for additional information. The Center for Biodiversity and Conservation (1-520-558-2396), located in the canyon’s North Fork, makes a few of its rooms available to the public at certain times during the year.

Commercial lodging near the entrance to the canyon includes:

Cave Creek Ranch (1-520-558-2334)

Portal Peak Lodge and Store (1-520-558-2223)

Arizona Sky Village (1-520-558-1128)

RV accommodations, located in Rodeo, just a few miles from the entrance to the canyon include:

Green Acres RV Park (1-505-557-2235)

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms