Desert Seeds

Betting on the Future

by Damian Fagan

Seeds by the hundreds, thousands, millions litter the desert floor. One study in the Sonoran Desert estimated the density to be between 5,000 and 10,000 seeds per square meter. Many are the products of annuals—the short-lived plants that last from a few weeks to less than one year. Others are from perennials—the longer-lived forbs, shrubs and trees. Some seeds are as tiny as a pinhead. Some are encased in spiny capsules or fleshy fruits. How they are packaged, how they get dispersed, when they germinate – that is, plants’ strategies for reproduction and survival – are as varied as the seeds themselves. Plants expend a fair amount of energy to produce their self-contained “next generations” because seeds hold the futures of their species.

Seed Dispersal

Dispersal strategies are designed to increase the likelihood of survival.

Where I live, here on the Colorado Plateau, for example, both the native cottonwoods (Populus sp.) and the non-native tamarisk (Tamarisk chinensis) produce copious amounts of seeds, following the strategy that mass production improves the odds for future survival. The cottonwoods start to release their downy seeds around the peak of spring runoff, filling the air with “snow in summer.” The cottonwood seeds, like tamarisk seeds, that land on moist soil, preferably new sandbars, germinate quickly. The taproots follow the descending water table through the summer.

Another southwest tree, the pinyon pine (Pinus edulis), follows a different strategy to spread its seeds, with the seed “set” varying each year, depending on conditions. About every seven years, the trees are laden with cones. Flocks of pinyon jays or Clark’s nutcrackers descend upon the trees and pluck the seeds from the cones. The birds know, by weight and color, which shells contain ripened nuts. They quickly reject and drop lighter or two-toned shells. A bird stuffs its crop – the sack-like expansion of its lower throat – with ripened nuts. Once its crop is full, the bird flies away to cache the seeds for winter consumption. Though the jays and nutcrackers recover most of their caches, they miss or forget some. It is those caches that yield the seeds that germinate to start the cycle anew.

Shrubs like the cliffrose (Purshia mexicana) or mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus), both members of the rose family, produce hard seeds with long, feather-like tails. As the seeds break away from the calyx, they drop to the ground. The wind disperses the seeds, with some landing on the ground with their seed-side down and their curled tails up. The wind turns the long tails like a corkscrew, literally screwing the seeds into the soil.

Other shrubs like coyote bush (Forestiera pubescens, a member of the olive family) or holly grape (Mahonia fremontii, a member of the barberry family) produce edible berries that contain small, hard seeds. After birds and animals eat the berries, the droppings, loaded with seeds that pass through the digestive tract, serve as self-contained fertilizer pellets when they fall to the soil.

Species like common milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) or dandelions (Taxaracum officinale) have bristles attached to their seeds that act as parachutes to catch the wind and increase dispersal.

The seed-containing capsule of a cocklebur has tiny burs along the top. The capsules attach to the animals’ fur, hitching a ride to new locations.

Germination of the Seeds of Annuals

After their distinctive flower sizes, shapes and colors, nectar or pollen rewards and flowering periods have played out critical roles in the process of pollination, desert annuals follow tremendously varying germination strategies.

Each year, the annuals produce a staggering number of seeds, which become widely dispersed. Only a small percentage, however, find the right conditions for germination soon after dispersal, and those few that do germinate quickly are further reduced by disease, wildlife consumption and undeveloped embryos. The great majority of the annuals’ seeds enter dormancy, the period of time they lie within the soil awaiting favorable conditions for germination. This period may be several weeks for some annual grasses or years for some wildflowers. This “seed bank” is analogous to a bank account. A person may deposit his entire paycheck, but withdraw incremental amounts over time. So, too, with the seeds. Not all the seeds deposited in the soil germinate in the first year. Some remain, awaiting better conditions. Others may simply get buried too deep in the ground to germinate. These represent a balance in the seed bank account.

One feature that protects many desert seeds from desiccation or premature germination is a tough seed coat, which somehow has to be broken down enough to allow water and oxygen to penetrate and reach the embryonic plant and reinitiate growth. Except for those seeds that require fire to destroy their coats, a typical seed may not need a cataclysmic event to break down its seed coat. For instance, something as simple as grains of sand or pebbles in the soil can abrade a buried seed, breaking down its coat. Soil microorganisms may also cause the decomposition of the coat.

With the breakdown of the coat, water and oxygen have a conduit to the embryo, but sometimes, even then, other environmental conditions enter into the equation if the seed is to germinate. Exposure to periods of cold temperature ensures that some annual seeds will germinate in the spring instead of the fall. Exposure to light is another critical factor for certain seeds. If a seed buried too deeply in the soil did somehow start to germinate, the seedling shoot could be restricted in its ability to reach the surface and the sunlight needed to initiate photosynthesis. Weed seeds, like Russian thistle (Salsola pestifer) are light sensitive and will germinate when they are brought to the surface through actions like tilling.

embryo, but sometimes, even then, other environmental conditions enter into the equation if the seed is to germinate. Exposure to periods of cold temperature ensures that some annual seeds will germinate in the spring instead of the fall. Exposure to light is another critical factor for certain seeds. If a seed buried too deeply in the soil did somehow start to germinate, the seedling shoot could be restricted in its ability to reach the surface and the sunlight needed to initiate photosynthesis. Weed seeds, like Russian thistle (Salsola pestifer) are light sensitive and will germinate when they are brought to the surface through actions like tilling.

Still other species contain growth inhibitors, which restrict the embryo’s growth in the event the seed coat is broken down but conditions are still not favorable for germination. Typically this inhibitor can only be leached away by sufficient soil moisture (heavy rains or snowmelt) passing through the seed. This triggers the breakdown of the inhibitor and the seed “believes” there is enough soil moisture to germinate and to survive.

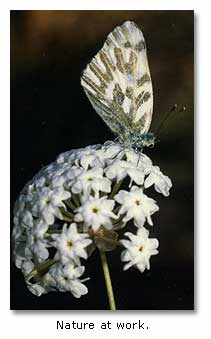

In the Sonoran Desert some desert annuals need a post-summer, pre-winter rainfall of greater than one inch to germinate. Others – the sand verbena (Abronia fragrans), for instance – have a better germination rate in the spring following winter rains or snowmelt. This interplay of temperature, moisture and light on seed germination varies greatly from species to species.

Researchers have discovered the pretreatment and germination conditions of temperature and light as well as soil chemistry and composition required for the germination of a number of different plant species. Their work helps arboretums, botanical gardens and university laboratories in developing reintroduction programs or management actions to help insure the preservation of species at risk.

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms