The Night Pat Garrett (Probably)

Shot Billy the Kid

Lincoln County

One of only two images acknowledged by experts to be Billy the Kid. This is a tintype believed to have been taken

in Ft. Sumner in 1879-80. A 3rd photo has been discovered, but not all experts have acknowledged it yet.

In the summer of 1881, Billy the Kid, hiding out around the hamlet of Fort Sumner in east-central New Mexico, should have known that Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett would try to hunt him down and kill him. The Kid had just broken out of jail in Lincoln, New Mexico, where he had been sent by a judge and jury in Mesilla, New Mexico, to hang for murder. He had shot two deputy sheriffs to death during his escape. He had learned that his notoriety had spread from coast to coast. He surely understood that Garrett would not just forget about him.

Billy the Outlaw

Although only 21, The Kid – also known as Henry McCarty, Henry Antrim or William Bonney, names reflecting the shards of his fractured family life – had already given a new dimension to the notion of “outlaw.” He had ridden with several gangs, hustled in the regional gaming halls, busted his companions out of imprisonment, stolen horses across the territory, rustled cows in New Mexico and Texas, fought in the infamous Lincoln County War, escaped from several jailhouses, gunned down at least four and possibly as many as ten men, and terrorized people from the Rio Grande to the Pecos River to the High Plains.

After his escape from jail in Lincoln, Billy the Kid had fled to Fort Sumner because he had friends there, including many among the Hispanic people, who – like their Spanish ancestors – admired a wild spirit and reckless audacity. Billy knew that he could count on them for a bunk and a meal in their adobe homes and sheep camps. He could rely on them to keep a secret. He thought that he could hang around the community until he could put some money in his pocket and head south for Mexico, beyond the reach of Pat Garrett, according to Robert M. Utley in his book Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life.

Meanwhile, from newspapers brought to him by his friends, Billy likely followed the media accounts of his breakout from the Lincoln jail. Undoubtedly, he realized that he had fired public interest. From New York to San Francisco, “people waited in fascinated suspense to learn whether the fearless young killer would remain at large,” according to Utley. Billy surely knew, too, that the governor of New Mexico had put a price on his head.

While criminal and murderous instincts lay at his core, Billy also had a certain raffish charisma, particularly among the Hispanics, whose language he spoke fluently. He had not only challenged the authorities, he had scorned danger, mocked death and charmed local daughters. He starred at village fandangos or bailes, where he danced to the polkas, waltzes and schottisches performed by the mariachis playing violins and the traditional convex-back guitars. He knew that many of the Hispanics thought of him as a folk hero.

Only the second photo ever authenticated of Billy the Kid, this photo is a tintype that was owned at one point by the estate of Pat Garrett. It came to light in Las Cruces, NM, and was verified as Billy the Kid (right) and his friend Dan Dedrick (left) in October of 2013. (You can read more about that here.)

A contemporary reporter, quoted by Utley, said that Billy, who stood about five feet and eight inches tall and weighed some 140 pounds, had “clear blue eyes, with a rougish [sic] snap about them; light hair and complexion. He is, in all, quite a handsome looking fellow, the only imperfection being two prominent front teeth slightly protruding like a squirrel’s teeth, and he has agreeable and winning ways.”

While he moved restlessly around Fort Sumner during that summer of 1881, Billy must have mused over the chronicle of events that brought him to a point where he had to think about leaving the country and heading south.

While he moved restlessly around Fort Sumner during that summer of 1881, Billy must have mused over the chronicle of events that brought him to a point where he had to think about leaving the country and heading south.

On a cold and snowy day six months earlier, Billy and his gang had been run to ground by Pat Garrett and a posse at a small rock cabin at Stinking Springs, a few miles east of Fort Sumner. Cal Polk, one of Garrett’s posse, remembered that “...Billy cride [sic] out is that you Pat out there. Pat says yes, then Billy says Pat why don’t you come up like a man and give us a fair fite [sic]. Pat said I don’t aim to. Billy says that is what I thought of you, you old long legged son of a bitch...” (The quote appeared in the Angelfire Internet site’s article “Billy the Kid’s Capture at Stinking Springs.) Billy and his gang soon starved out. They surrendered.

Under guard by Garrett and his men, Billy and the other prisoners rode by wagon to Las Vegas, New Mexico, where they were met by a boisterous mob. Billy smiled and waved to the crowd, enjoying the attention. In jail, Billy was “cheerful and upbeat,” said a reporter for the Las Vegas Optic, according to the Internet site “Chronology of the Life of Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War, Part 9.”

On December 27, still under guard by Garrett and his men, Billy and the other prisoners boarded a train. It took them to Santa Fe, where they spent three months in jail. While he wrote letters from his cell to the governor of New Mexico, pleading for a pardon, Billy and his fellow gang members did their best to dig a tunnel to freedom. After officials discovered the escape attempt, Billy found himself in solitary, shackled to the floor of a cell as dark as a cave.

Near the end of March, Billy and one other gang member, guarded by three deputy U. S. Marshals, including an old enemy, Bob Olinger, boarded a train southward for Mesilla, where they would face trial. Billy endured tormenting by Olinger throughout the trip.

On April 9, in a one-story adobe building on the southeast corner of Mesilla’s plaza, Billy stood before the bench, the jury having found him guilty of gunning down Sheriff William Brady in a revenge killing in Lincoln three years earlier. On April 13, Billy heard his sentence: He would be sent to Lincoln, where he would be hanged.

On April 16, Billy began the trip, by wagon, to Lincoln, under a seven-man guard, including, again, the hateful Bob Olinger. For the whole five-day trip, Billy, shackled to the floor of his wagon, ignored Olinger’s taunts. Once in Lincoln, Billy came once more under the custody of Pat Garrett, who had him shackled to the floor of his courthouse cell and placed under the guard of Olinger and Deputy James W. Bell.

Late in the afternoon 12 days later, Billy watched as Olinger left the jail with five other prisoners, heading to the hotel across the street for dinner. Billy asked Bell to take him outside to the privy. On the way back into the courthouse and his cell, Billy, although shackled with hand and leg cuffs, bludgeoned Bell with the chains. He seized the deputy’s pistol, according to Utley. Billy shot the deputy, leaving him to stagger outside and collapse, dying almost immediately in the arms of a passerby named Godfrey Gauss. Though impeded by his shackles, Billy quickly made his way upstairs. He raided the armory, taking Olinger’s prized double-barrel shotgun, a brand new firearm. Billy stood at an open second-story window like a wolf spider waiting for prey. Within moments, as he anticipated, he saw Olinger pass on the ground below, rushing back from the hotel to the courthouse to investigate the gunfire. Godfrey Gauss shouted, “Bob, the Kid has killed Bell.” Billy looks down on Olinger and said, mockingly, “Hello, Bob.” Startled, Olinger looked up and saw Billy in the window above. He said, “Yes, and he’s killed me, too.” And Billy did. He fired both barrels full into the face and chest of his tormentor, killing him instantly.

With the help of friends, Billy freed himself from his shackles. He “borrowed” horses. Over the next two weeks, he drifted south along the drainage of the Pecos River, northeast across the High Plains of Texas, then back southwest to his old haunts around Fort Sumner. Now, he looked south toward Mexico. He thought about freedom from Sheriff Pat Garrett’s pursuit.

Tracking Down Billy the Kid

Garret, who would become a legend in his own right, thought that Billy would surely head south immediately, into Mexico, beyond the reach of the law. Without knowing Billy’s whereabouts, Garrett waited, biding his time. He began to read newspaper accounts and hear rumors of Billy the Kid “sightings” from Mexico to Tombstone, Arizona, to Denver, Colorado, to Austin, Texas. Still Garrett waited, through May, through June, into July.

Garret, who would become a legend in his own right, thought that Billy would surely head south immediately, into Mexico, beyond the reach of the law. Without knowing Billy’s whereabouts, Garrett waited, biding his time. He began to read newspaper accounts and hear rumors of Billy the Kid “sightings” from Mexico to Tombstone, Arizona, to Denver, Colorado, to Austin, Texas. Still Garrett waited, through May, through June, into July.

Garrett, an ex-buffalo hunter, had drifted into east central New Mexico in 1878, according to Utley. A lanky young man well over six feet tall, Garrett had swiftly established a reputation as “a tough, resolute fellow, quiet and soft-spoken but not to be trifled with. ‘Coolness, courage, and determination were written on his face,’ noted one who knew him.” Called “Juan Largo,” or “Big John,” by the Hispanics, he, like Billy, danced at local fandangos to the music of the mariachis. He married an Hispanic woman, and after her premature death, he married another Hispanic woman. Garrett had friends of his own in the region. He won his office on a “law and order” platform in the lawless and disorderly Lincoln County.

Near mid-July, Garrett finally got reliable intelligence on Billy’s location. His quarry, he learned, had not run immediately for Mexico, but had holed up somewhere around Fort Sumner. Garrett got ready to pounce. He enlisted two deputies, John W. Poe and Tom “Kip” McKinney. They headed for Fort Sumner.

Showdown Time

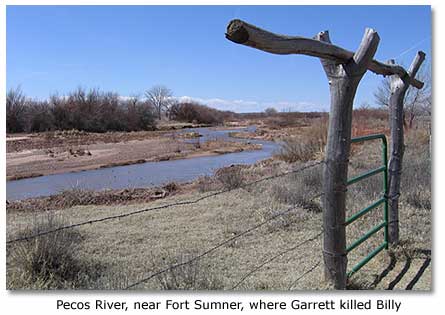

As both The Kid and Garrett certainly knew, Fort Sumner had been the setting for memorable chapters in the history of the Southwestern frontier. During the Civil War, it had served as a concentration camp for the Navajos and Mescalero Apaches, who lost many of their people in the insect-infested fields and fetid waters of the Pecos River valley. It had become the northernmost point on the Pecos River leg of the Goodnight-Loving Trail, which Texas cowmen used to drive tens of thousands of longhorn cattle to markets as far north as Wyoming. After abandonment by the Army in 1868, the fort – the heart of the community – fell into the hands of Lucien B. Maxwell, a cattle baron, and at one time, the largest private landowner in the United States. The former officers’ quarters had been recast as a large and lavish home for the family and servants, much like a Mexican hacienda. The compound passed into the hands of son Pete Maxwell when Lucien died in 1875.

Both Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett knew the Maxwell family well. Neither knew, however, that, by sheer coincidence, they would converge at the Maxwell place on the warm moonlit night of July 14, 1881.

Around 9:00 p.m., said Utley, Billy lounged on the ground with friends in a nearby peach orchard, chatting in Spanish. He wore his customary sombrero, boots, and a dark vest and pants. He rose from the ground, walked out of the orchard, lept over a fence, and disappeared into the Maxwell compound. He either went to the room of a friend (or, possibly, to the room of Celsa Gutierrez, Pat Garrett’s sister-in-law) along the old officers’ row.

Around 9:00 p. m., Garrett, with Poe and McKinney, appeared in the peach orchard, planning to talk in secret with Pete Maxwell, hoping he might know something current about Billy. Garrett and his men kept to the shadows. They saw men sitting on the ground. They heard them speaking in Spanish. As they watched quietly, they saw in the moonlight someone, who wore a sombrero, boots and dark vest, rise from the ground, walk out of the orchard, leap over a fence and disappear into the compound.

Near midnight, they moved silently to the southeast corner of the Maxwell house, just outside Pete’s bedroom. Garrett left Poe and McKinney on the porch. He entered quietly through the open door into the darkened bedroom to awaken Pete and question him.

Near midnight, Billy, having taken off his hat, vest and boots, decided that he wanted something to eat. He built a cook fire. He took his knife – and, apparently as a precaution, his Colt pistol – and he walked, in his socks, across the compound to cut a piece of meat from the carcass of a freshly killed yearling steer hanging from a rafter above the porch outside Maxwell’s bedroom.

Simultaneously, inside the bedroom, Garrett started to question Maxwell, who was aggravated about having been awakened.

Just outside the bedroom, on the porch, Billy discovered the shadowy figures of Poe and McKinney. “Quien es?” Billy demanded, leveling his pistol on Poe. “Who are you?” He moved toward the door to Maxwell’s bedroom, probably thinking instinctively that it would serve as a sanctuary.

Garrett and Maxwell heard the anxious voices on the porch. They fell silent.

Billy entered the room, his pistol ready. “Who are those fellows outside, Pete?” he asked Maxwell, according to Utley.

“That’s him!” Maxwell said to Garrett.

Billy, startled, saw the dark form of Garrett. “Quien es?”

“...I jerked my gun and fired,” Garrett would say later, quoted by Utley.

Afraid that Garrett may have wounded a lion in the darkness, Garrett and Maxwell scrambled out of the room, which fell silent.

Garrett said, “...I think I have got him.” They heard nothing.

Garrett watched as Maxwell lit a candle and placed it in the window of the bedroom to light the interior. Garrett, Poe and McKinney peered through the window, and in the flickering light, they could see a figure sprawled on the floor, motionless.

Billy the Kid, with Pat Garret’s bullet lodged in his chest, just above the heart, lay dead. Bereaved Hispanic women gathered at the sound of the gunfire. They carried The Kid’s body to a nearby room, laying his body on a bench. They placed “...lighted candles around it according to their ideas of properly conducting a ‘wake’ for the dead,” said Deputy Poe, as quoted by Utley. The afternoon of the next day, the community buried Billy the Kid in the Fort Sumner cemetery, next to two old friends and gang members.

Or was it really Billy the Kid they buried that hot July afternoon?

Now Comes Brushy Bill

In 1949, an aging man called Ollie L. “Brushy Bill” Roberts, who lived in Hamilton County, Texas, about 100 miles southwest of the Dallas/Fort Worth area, declared that Pat Garrett had not killed Billy the Kid that night in Fort Sumner, according to the Angelfire Internet site. Rather, Brush Bill contended, Garrett had killed another man, whose name was Billy Barlow. Brushy Bill claimed that he was the real Billy the Kid. He said that he, in fact, had escaped and fled Fort Sumner. He said he had lived in Mexico with the Yaqui Indians until things in the U. S. cooled down, then he returned to work, he claimed, as a Wild West performer, a law enforcer, and a mercenary, living under a dozen different aliases. He said that he served with Pancho Villa in the Mexican Revolution. He married four times.

Undeniably, Brushy Bill bore certain physical resemblances to Billy the Kid. He appeared to know an exceptional amount about Lincoln in 1881, The Kid’s escape from the Lincoln jail, and events in Fort Sumner. He had old acquaintances who vouched for him.

On the other hand, Brushy Bill never seemed to have explained why so many people who knew and revered Billy the Kid grieved at the funeral on July 15, 1881. Brushy Bill’s version of the killing finds no support in any other contemporary account. His story sometimes appears to run contrary to known history. Photographs of Brushy Bill as a young boy do not seem to match up precisely with the one known photograph of Billy the Kid.

Unfortunately, before anyone could resolve the contradictions in the story, Ollie L. “Brushy Bill” Roberts collapsed and died of a heart attack in Hico, Texas, on December 27, 1950. The question of whether Pat Garrett really shot Billy the Kid that night in Pete Maxwell’s bedroom remains unanswered to this day.

Tracking Down Billy the Kid

You can track Billy the Kid – as a child – from New York City to Indianapolis, to Wichita, to Denver, to Santa Fe, to southwestern New Mexico’s Silver City. You can track him – as an outlaw – from eastern Arizona across New Mexico to the Texas Panhandle.

You will find that Lincoln, essentially a museum frontier village located in the Bonita River canyon between eastern New Mexico’s Sacramento and Capitan Mountains, is a good place to start your quest. A number of the historic sites and buildings from the Billy the Kid era have been preserved. They are open to visitors. For additional information, contact:

Visitors Center

Highway 380

Lincoln, New Mexico 88338

Phone: 1-505-653-4025

Fort Sumner, located on the Pecos River about an hour and a half drive north of Roswell, is a good second stop. At the old military fort, you will find a marker, showing the location of the Maxwell house, where Garrett shot Billy the Kid, and you can visit The Kid’s grave, just south of the Old Fort Sumner Museum. For additional information, contact:

Fort Sumner Chamber of Commerce

707 North 4th Street

P.O. Box 28

Fort Sumner, New Mexico 88119

Phone: 1-505-355-7705

Fax: 1-505-355-2850

E-mail: info@ftsumnerchamber.com

There are a number of other places where The Kid left his fingerprints. For instance, he sold stolen cattle, charmed the girls and played cards in the mining community of White Oak, now an interesting ghost town with an intriguing cemetery located about a 45-minute drive from Lincoln, in the western end of the Capitan Mountain range. The Kid hung out around the old mill on the main street through Ruidoso, about an hour’s drive up into the Sacramento Mountains from Lincoln. He got involved in a shootout at Blazer’s Mill near Mescalero, about a 20-minute drive southwest of Lincoln, on Highway 70. He faced trial, conviction and sentencing in a building still standing in Mesilla, in the Rio Grande Valley just west of Las Cruces in south-central New Mexico. He purportedly busted one of his buddies out of jail in a building still standing in San Elizario, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley about 20 miles downstream from El Paso.

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Your GPS Navigation Systems

May Get You Killed

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Desert Survival Skills

- Successful Search & Rescue Missions with Happy Endings

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert

Survival Tips for Horse and Rider

- Preparing

an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms