Marshal South

The Years Before Yaquitepec

by Diana Lindsay

author The Ghost Mountain Chronicles

Ghost Mountain was named by Tanya and Marshal South in 1930 when they began their “great experiment” in primitive living, which was later chronicled in the pages of Desert Magazine. Nowhere in the pages of the magazine can a reader find background on the Souths. Their life, as far as the magazine was concerned, began when they commenced building their home, called Yaquitepec, on the waterless ridge of Ghost Mountain in Blair Valley.

Before the magazine, before Ghost Mountain, and before Tanya, there was Margaret, the Army, and Arizona.

Margaret Frieda Schweichler was 21 years old when she met Marshal while working as a civilian secretary with the Army Quartermaster Company where Marshal worked as a clerk. Two years later they were married on January 9, 1918, in Bisbee, Arizona, when Marshal was 29 years old.

Margaret Frieda Schweichler was 21 years old when she met Marshal while working as a civilian secretary with the Army Quartermaster Company where Marshal worked as a clerk. Two years later they were married on January 9, 1918, in Bisbee, Arizona, when Marshal was 29 years old.

Margaret was an artist who painted in oils. Marshal called her “Pusstat” because she loved cats. They had a small home in Douglas near Camp Henry J. Jones where Marshal worked. Almost a year after their marriage Marshal Jr. was born on December 5, 1919. Sometime before that date, Marshal was discharged from the Army (the exact date is unknown because his military records were destroyed in a fire in 1973), and in June 1920, Margaret asked Marshal to leave.

Marshal was distraught and spent nights sleeping out in the open desert “sinking into hopeless degradation; sleeping on boxes and out in the desert in an overcoat; chased off by the police,” as he recounted in a letter written in December 1922. He had hoped Margaret would take him back, and he repeatedly tried to return to her only to be rebuffed.

He eventually drifted back to Oceanside, California, where his mother lived and found a job as a carpenter at the Rosicrucian Fellowship in Oceanside. He wrote regularly to Margaret, sending money and gifts, and Margaret wrote back, sometimes including drawings by “Ratzin” (Marshal Jr.). The fact was that Margaret always loved Marshal, but could not live with him. She was ambitious and wanted a good provider. Marshal admitted that he could never be “a successful provider” because “earthly prosperity and comfort” meant “nothing or next to nothing; it is toward the world of ideals and thought and philosophy that my steps lead,” he explained in a letter.

Marshal felt they had inflicted real pain on each other, and he acknowledged that he had “brought trouble and financial disaster, disillusionment, and shattered dreams” to Margaret, but she had “brought the unspeakable torture and agony of useless and rejected love and the tearing separation from the love of my boy.” Marshal sunk into depression and considered suicide.

Then he met Tanya who worked in the healing department of the Rosicrucian Fellowship. He later credited Tanya with saving his life by binding up his “broken heart” and bringing “the rest of peace to a tortured soul.” He told Margaret in a letter to her that where she had opened the door of life to him, Tanya had opened the door which leads beyond life.

Tanya had worked at the Fellowship since 1920 when she had moved to Oceanside from New York City. She was born on November 4, 1897, in Zhmerinka, Podolsk, near Brahilov in the Russian Ukraine near the Romanian border. Her orthodox Jewish family emigrated to the United States in 1906 when Tanya was eight years old. She was educated in New York City schools and after graduation, she worked as a secretary on Wall Street. Her interest in the occult and spiritual pursuits led her to the Rosicrucian Fellowship.

Tanya was also a writer and poet who submitted articles and poems to the Rosicrucian Fellowship Magazine, Rays from the Rose Cross, that were published regularly beginning in May 1920. She was a small woman—five feet, three inches tall—with blue eyes and light brown hair (Marshal was five feet, eleven inches tall, weighted under 140 pounds, and had brown eyes and brown hair).

In December 1922 Marshal asked Margaret for a divorce, stating that “it is not fair of you to keep me tied to you and at the same time refuse to be a companion to me….for two years you have pushed me from you and urged me to seek someone else. And I could not do it. I clung to the hope of you. And finally Fate has intervened.”

He told Margaret that if Tanya loved him she “would go with me to the end of the earth.” He said that Tanya had “risen far above money. For she does not want it nor value it. She lives simply and dresses simply. She is not afraid of poverty and it is the higher things of life that she desires—not the material.”

Before a legal divorce was obtained, Marshal and Tanya married on March 8, 1923, in Santa Ana, California. On the wedding document Marshal claimed it was his first marriage. Marshal and Tanya were later remarried on September 19, 1938, in San Diego. Their honeymoon was spent tent camping on a beach in Oceanside.

After they were married they moved to Los Angeles where Tanya took a job with an oil company and Marshal began working for an “office building concern.” Soon thereafter, Marshal moved back to Oceanside to take care of his ill mother while Tanya continued working in Los Angeles. His mother, Annie Richards, died on August 1, 1924. After her death, he moved back to Los Angeles.

In the following years they both pursued their interest in writing. Marshal was no longer writing poetry, perhaps not to compete with Tanya. He wrote short stories and worked on novels. He had success finding publishers for his short stories, but it was not until 1936 that he was successful in finding a publisher for his novels.

In 1925 or 1926 Marshal and Tanya began taking camping trips to the desert, exploring sites along San Diego County’s unpaved Highway S-2. They stayed often at the Vallecito Stage Station (before it was restored), until Tanya was frightened by an apparition of a white horse she claimed to have seen.

In 1928 the Souths moved back to Oceanside from Los Angeles. Their decision to move to the desert permanently in 1930 was probably driven by many factors. The Depression clearly limited Marshal’s income as a writer and made it difficult to make ends meet. He later explained in an article he wrote for the Saturday Evening Post that they did not want to be slaves to making money. They wanted to pursue more creative and spiritual endeavors. They wanted peace and solitude, and they wanted to experience a total sense of freedom—mentally and physically. He said they “were tired” and “out of step….temperamental misfits and innate barbarians…not equal to the job of coping with modern high-power civilization.”

In all likelihood, South was also influenced by writers who wrote about a return to nature—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Hermann Hesse. He also may have been influenced by the German natural-living movements that were spreading to the United States. Interestingly, a similar return to nature experiment was being conducted at the same time in Palm Springs, centering in Tahquitz Canyon, unbeknownst to South.

Against the advice of South’s brother and friends, Tanya and Marshal packed their Model T in February 1930 and drove to the desert, stopping in Blair Valley. To Marshal, it may have seemed like returning to his boyhood home in Australia, similar in landscape and isolation. To Tanya, the city girl, it was an adventure that would allow her to focus on her spiritual interests. It would be difficult and it would call for a certain amount of suffering, which she viewed as necessary for spiritual evolvement.

By the time that Rider Del Sol South was born on January 22, 1934, they had established a comfortable home on the waterless ridge of Ghost Mountain.

The Great Experiment Comes to an End

Visitors to the ruins found on Ghost Mountain in Blair Valley, on the western edge of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, may find it hard to believe that there was once a comfortable home found there that was originally built beginning in 1930. The builders wanted a home that was isolated yet inspiring that would allow them the freedom to pursue their own interests, totally unfettered by the demands of civilization.

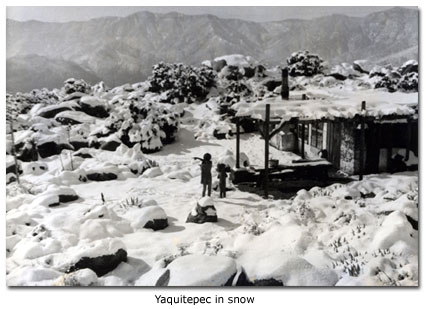

The adobe home belonged to Marshal and Tanya South, and it was built over several years as they were dependent on water to make the adobe home and cement cisterns. At first they carried the water up the one-mile steep trail, 12 gallons per trip, until the new cisterns were able to catch and store rainwater. All building materials, including bags of heavy cement, and supplies were carried up a trail they also had to construct. At the end of several years they had a very livable home, which they called Yaquitepec (YAKeete-PECK), naming it after the freedom-loving Yaqui Indians of Sonora, Mexico, and “tepec” because it was on a hill.

The home faced magnetic east to catch the rays of the morning sun. In its final form in the l940s, the interior of the house measured 15 feet by almost 40 feet. It looked larger because the adobe walls were from 1-2 feet thick. There were basically two rooms. The northern room was the front room with the entrance and large windows. The west side of this room was screened and mouse-proof and was used to store food. The central part of the south room had a large adobe stove, a fireplace, a dining table, and two food coolers. A bed area was next to the southern wall.

A circular 12-foot deep storage cellar with an 8-foot diameter was located behind the house. The Souths had begun work on a third room to the north, but only the wall was completed before they left Yaquitepec. The Souths used a large shaded ramada outside as an additional room, and during summer, they slept under the ramada.

They wanted to live as naturally as possible, emulating the Native Americans whenever they could. They collected some native foods that supplemented what they purchased. Primarily they harvested mescal or agave each year as well as cactus fruit and chia seeds. They were dependent on whole grains, which they purchased in town and ground in a hand mill. They attempted to grind the whole grains Indian fashion on granitic rock, but learned very quickly that they could not separate the gravel from the ground grain. They also purchased potatoes, beans, and fruit in season. Later when they had children, they purchased condensed milk in cans until they bought two goats that provided milk and cheese. They had honey from beehives they kept at the foot of Ghost Mountain. Marshal had a rifle and would hunt for rabbits.

All of their dishes and storage pots were made from local clay on Ghost Mountain and fired in a kiln near the house. Yucca leaves were used for webbing for chairs and to make sandals and rope. They had a small hand loom to weave cloth and blankets, and they made their own candles and soap.

Everything else they needed was purchased in town from income received from Marshal’s writings. During the 1930s, that was from the sale of short stories and novels.

The dynamics of Marshal’s and Tanya’s relationship on Ghost Mountain changed dramatically when the children were born. Tanya was city bred and never felt comfortable raising children on an isolated mountaintop. She was constantly worried about their safety and their future. Marshal had been raised in the Australian outback. He felt very safe and comfortable living in isolation. With the children came the beginning of many arguments and disagreements about raising children.

Each of the three children was born in Oceanside. Tanya moved there each time during her last month of pregnancy. Rider Del Sol South was born in 1934. He was named for H. Rider Haggard, who wrote King Solomon’s Mines and other novels. Rudyard Del Sol South was born in 1937. He was named for Marshal’s favorite writer, Rudyard Kipling. Victoria Del Sol South was born in 1940. She was named for Queen Victoria and for the Spirit of Victory during the dark days of war torn Europe.

The story of the Souths would have been that of any other desert homestead family except for the fact that they became a family everyone knew because of the monthly columns written for Desert Magazine, beginning in December 1939. South received the one-year contract to write a series of 12 articles after “Desert Refuge” appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in March 1939. In that article, he described his successful experiment in primitive living and his family’s Robinson Crusoe existence on Ghost Mountain.

The popularity of his series called “Desert Diary” led to a permanent monthly column that ran continuously until Tanya filed for divorce in the fall of 1946. After the separation, South wrote a series for Desert Magazine entitled “Desert Trails” until he died in October 1948.

First and foremost, South was a good writer who knew his audience. He wrote with a lyrical quality and painted vivid word pictures. He wrote about the desert with passion. “Either you will love it or you will hate it. If you hate it you will fly from it and never wish to see its face again. If you love it, it will hold you and draw you as will no other land on earth.”

Desert Magazine readers adopted his family, sending so many Christmas presents yearly that it took literally two weeks to open all of them. The children did not lack for toys or books. The Souths had an extensive correspondence with readers that led to about 50 guests a year visiting Yaquitepec. They began enforcing their “no clothes” rule to control the number of guests visiting. Guests included representatives from the Peruvian Consulate, the Missouri Botanical Garden, and James L. Kraft who was seeking advice about raising cactus. For years afterwards, the Souths received a large box of Kraft cheese for Christmas.

South wrote not only about his family’s adventures and the desert, but also about his unconventional philosophy of life. The naysayers, his supporters, and even his guests never knew that things were not going well on the personal side. He took care to only write about the positive aspects of life on Ghost Mountain. He made life there sound so interesting. From Tanya’s perspective, however, it was a very difficult life with no future. It was even more difficult for her because of Marshal’s steadfastness to his own personal beliefs and his inability to compromise and meet Tanya part way.

Personal tension continued to mount as they both voiced different opinions over how the children should be raised. The two moves away from Yaquitepec in the mid 1940s set the stage for the divorce and final move.

Because water was such a problem with a growing family that now consisted of three children, two goats, and two burros, the Souths decided to move in the fall of 1942. They sealed up Yaquitepec, packed their Model A Ford and trailer, and went in search of a new home in Utah or Arizona. But with no money to buy land with the needed isolation to live their chosen lifestyle, the Souths returned to Yaquitepec a year later with determination to improve and enlarge their cisterns. Before their plans could be completed, the U.S. Navy asked them to move as Ghost Mountain was in the flight path for an artillery range.

Neighbors Everett and Lena Campbell came to the rescue and offered them the use of a comfortable stone lined shack in Storm Canyon from July or August 1945 to June 1946. In June the Navy moved the family and all of their belongings back to the foot of Ghost Mountain. Marshal would not allow the Navy to carry their household goods to Yaquitepec because the officer in charge insisted on using a caterpillar tractor that would have left a tremendous scar on the mountainside. So the Navy left them to carry their own goods back up the hill.

Unbeknown to anyone outside of the immediate family was the increased tension between Marshal and Tanya. It finally came to a head a few months later when Tanya summoned up the courage to file for divorce. As divorce could only be granted for cause, Tanya exaggerated the charges.

Marshal did not contest the divorce because he felt the children would be better off with their mother. He wrote the judge and told him to give everything to Tanya. He only requested that the land not be sold until the youngest child was of age. He wanted to make sure that if Tanya could not survive in the city that she would have a home she could return to.

Tanya’s attorney briefed Rider on what to say at the divorce proceedings in January 1947. As instructed, he said that his father had beaten and threatened his mother. The fact was that he had not. But he stated that to prove cause, and a judgment favorable to Tanya was granted.

Marshal never recovered from the divorce. His whole world was shattered. The experiment in primitive living had failed. He died in October 1948, and he was buried in an unmarked grave, paid for by Myrtle and Louis Botts and Marshal Jr. and his mother Margaret. Tanya and the children did not attend the service, but they visited the funeral home in El Cajon before the body was taken to Julian.

Marshal never recovered from the divorce. His whole world was shattered. The experiment in primitive living had failed. He died in October 1948, and he was buried in an unmarked grave, paid for by Myrtle and Louis Botts and Marshal Jr. and his mother Margaret. Tanya and the children did not attend the service, but they visited the funeral home in El Cajon before the body was taken to Julian.

Years later the location of South’s grave was lost because the cemetery records were burned in a fire. The discovery of a letter written by Myrtle Botts to Marshal Jr. while doing research for the South book has established the location of the grave. The letter gives detailed instructions on how to find the gravesite. In January 2005, the South children placed a headstone on their father’s grave.

Tanya lived to be a few months short of 100 years. She died in 1997. She remained bitter about Marshal and her life on Ghost Mountain to the end. In retrospect, her plan for the children seems to have been best for them. All have had very successful lives, and each has had their own happy and bright children.

More about Marshal South and the Ghost Mountain Chronicles book.

Related DesertUSA Pages

- Anza-Borrego Desert State Park

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Your GPS Navigation Systems

May Get You Killed

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Desert Survival Skills

- Successful Search & Rescue Missions with Happy Endings

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert

Survival Tips for Horse and Rider

- Preparing

an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms

Click here to see current desert temperatures!