Pancho Villa

Raid of Columbus, NM

by Jay W. Sharp

Jack Thomas, deputy sheriff, and other officials sensed “something in the air,” said Bill Rakocy, Villa Raids Columbus, N. Mex. Mar. 9, 1916. “They had noticed strange Mexicans in town—many ‘friendly Mexicans’ became silent and some left town.” Juan Favela, a local ranch foreman, complained that “the air was bad.”

In spite of the omens, however, the 400 citizens of Columbus, New Mexico, three miles north of the border town of Palomas, Chihuahua, believed themselves generally secure in those pre-dawn hours of March 1916. They had followed, of course, the violent conflict in their neighboring country, where revolt against dictatorship and the federales (government troops) and land monopolies and the subsequent struggle for national power would claim nearly a million lives, some six percent of Mexico’s total population at the time. They knew, too, that Pancho Villa’s marauders had pillaged along Mexico’s northern border, raising the specter of attack at Columbus. Still, the citizens felt secure because they thought the U. S. 13th Cavalry Regiment, dispatched by Commanding Officer General John “Black Jack” Pershing from Fort Bliss, El Paso, Texas, to the nearby Camp Furlong, would protect them. They felt safe because they could scarcely believe that Pancho Villa would take the risk of crossing the border to challenge a U. S. community and military encampment. What they may not have realized was that there were few risks that Pancho Villa would not take.

Pancho Villa

Villa, “…a man born of Porfirian [after the Mexican despot, Porfirio Díaz] illegality, entirely primitive, entirely uncultured and devoid of schooling, entirely illiterate…,” according to Martín Luis Guzmán in his preface to Memoirs of Pancho Villa, had two qualities that cannot be taught: charisma and daring. Those characteristics endeared him to the impoverished people he inspired in revolution and led in victorious battles.

Both a Robin Hood and a warlord in Mexico’s northern Chihuahuan Desert, Villa broke up the hated land monopolies and distributed the parcels to widows and orphans. He stole tens of thousands of pesos and gave the money to the poor. He stole cattle from the hacendados, the great landowners, and sold the stock north of the border, using the money to buy arms. He stabilized the Chihuahuan economy by printing his own currency and threatening to shoot or jail anyone who refused to accept it. He danced with the women all night at the local fiestas, although he refused to drink. He married officially, according to one report, 26 times.

He would also kill you on a whim.

“Villa was hated by thousands, but beloved by millions,” they said in Mexico, according to Robert Ryal Miller, Mexico: A History.

Get ready now, federales,

Be prepared for very hard rides,

For Villa and his soldiers

Will soon take off your hides!

From a mariachi corrido (narrative folk song), according to Miller.

Villa became known as El León del Norte, the Lion of the North.

Although no one knows his motivations for sure, El León apparently looked across the border, at the village of Columbus, and saw a possibility for taking revenge on the United States for recognizing one of his political enemies. He saw a chance to pay back a Columbus merchant, Sam Ravel, who had purportedly cheated him. Probably most importantly, he saw the potential for capturing needed supplies and armaments – especially machine guns – for his forces, known in Chihuahua as Villistas. Besides all that, his spies had assured him that the U. S. Army’s 13th Cavalry posed a minimal threat.

In his October 1916 Manifesto to the Nation, said scholar Haldeen Braddy, in his monograph Pancho Villa at Columbus: The Raid of 1916 Restudied, Villa showed his venom. He would call the Americans “Our eternal enemies…and…the barbarians of the North.”

Columbus

Columbus, overlooked from the west by a small peak called Cootes Hill, lies in a Mesquite- and cacti-filled basin of the Chihuahuan Desert, along the historic track of El Paso & Southwest Railroad. The community, a desert outpost only a few years old at the time, served as rail watering stop and as a border crossing station. In 1916, residents and troopers could take the train east, about 60 miles, to El Paso, Texas, or west, about 130 miles, to Douglas, Arizona. They could travel by Model T Ford, wagon or horse north, about 35 miles, to Deming. “The straggling town…” said Braddy, “consisted of a cluster of adobe houses, some frame buildings, a railroad station, two hotels, a few other business establishments, and an army camp.”

Columbus’ commercial center, serving both the residents and the troopers, lay immediately north of the railroad station, which did a brisk trade in passenger travel. The businesses included, said Braddy, a drug store, a grocery store, a hardware store, a bank, a post office, a movie theater, an embalmer and undertaker, and two hotels. Sam Ravel owned one of the stores and the frame, two-story Commercial Hotel.

As you can see in historic photos in Rakocy’s book, the businesses promoted their wares on signs and posters. The drugstore, for instance, advertised cigars, prescriptions, candy, stationery and Kodaks. The grocery store offered two dozen Sunkist oranges for 15 cents, three pounds of New Red Potatoes for 10 cents, and a pound of rice for a nickel. The bank encouraged “every young man or woman” to open an account, touting the institution’s “capital and surplus” of $50,000. Model T Fords, military trucks and horse-drawn carriages and wagons parked along the village’s dirt streets.

Camp Furlong officers took quarters around the perimeter of the commercial center, and its enlisted men, in barracks south of the rail station. The troopers stabled their horses in open shed stables just east of the barracks. Commanding officers set up their headquarters between the rail station and the barracks.

As darkness gathered over Columbus and Camp Furlong on Wednesday night, March 8, 1916, the community grew still. Merchants turned off their lights and locked their doors. Residents fed their livestock. Families gathered for dinner, some under the soft yellow glow of kerosene lanterns, then turned back their beds for the evening. Commander Colonel Herbert Slocum and several other officers had motored north, up to Deming, for a polo match. Sentries had taken up their posts. Columbus felt at peace with the night.

Pancho Villa Comes

About one o’clock in the morning, March 9, 1916, Pancho Villa’s raiders – some 485 men – cut the border fence about two and a half miles west of the crossing to Palomas. Wearing their traditional crossed bandoliers and high crowned sombreros, the Villistas streamed, on their horses, through the opening, and in the darkness, they headed “slowly and quietly,” said Braddy, across the desert floor to the north and Columbus. Less than a mile from the community, Villa gathered his column and called a dismount. He issued orders to his officers, Dorados (Golden Ones), tested and faithful comrades-in-arms from the early days of the Mexican conflict. They would lead their men to strategic positions. From there, they would ignite the attack and converge on Columbus’ businesses and on Camp Furlong. Villa would wait with reserves near Cootes Hill. Some of his men remounted. Others prepared to move forward on foot. In the pre-dawn darkness, a little after 4:00 am, he said, “Váyanse adelante, muchachos!” (in effect, “Go get ‘em, boys!”), setting the stage for battle.

Gunfire and Chaos

According to Braddy and Rakocy, Private Fred Griffin, sentinel at regimental headquarters, immediately south of the rail station, saw Villa’s raiders first, shadows in the darkness. He challenged them. He received a hail of rifle bullets in answer, suffering mortal wounds, but he exacted a price, killing three of the Villistas before he died.

Columbus’ civilians, startled awake by the crack of gunfire, rapidly became engulfed by rifles firing, windows shattering, doors splintering, the raiders’ yells—Viva Villa! They saw men riding and running, swarming and plundering through the streets like killer bees. They soon saw flames enveloping buildings, including Sam Ravel’s Commercial Hotel. Some panicked, fleeing through the cold night to the sturdiest buildings or into the desert, where they hoped to find shelter. Others took up arms, fighting to save their homes and businesses. Women and children screamed.

Railroad pumper Milton James tried to rush his pregnant wife from their home to the Hoover Hotel, which offered the protection of thick adobe walls. She took a bullet that killed both her and her unborn child.

Mrs. Parks, a telephone switchboard operator, stuck by her post and notified the world that Columbus had come under attack. She suffered cuts from shattering glass, but survived.

Mrs. Frost loaded her three-month-old baby and dragged her wounded husband into their car, and she drove her family north, out of the range of the gunfire, toward Deming and safety.

Mrs. Smyser, wife of one of the 13th Cavalry’s officers, and two children climbed out a window of her home to the sound of pounding on her front door, and they hid first in an outhouse then raced through cacti thorns and nettles and into the desert.

Mrs. Riggs, frantic, hiding in her house, almost smothered her five-month-old baby by stuffing a pillowcase into its mouth to keep it silent as the raiders searched nearby. With the searchers moving on and her baby growing limp, she removed the pillowcase, and the child caught its breath, surviving near suffocation.

Three men and a woman, patrons of the Commercial Hotel, fell captive, dragged from their rooms. The three men died before Villista rifles. The woman shouted “Viva Mexico!” and won her freedom. Unarmed John Walton Walker, dragged from the arms of his new bride, fell to Villista bullets on the hotel stairs. Another patron, Steve Birchfield, blithely wrote personal checks to his each of captors to win his freedom.

Arthur Ravel, Sam’s 14-year-old son, fell captive to the raiders, who dragged him from his home and hauled him to his father’s Commercial Hotel. He broke free when two of his captors fell to gunfire, and he ran, in his underwear, three miles through the cold night into the desert.

Sam Ravel, ironically, missed the whole thing. He had gone to El Paso for minor surgery.

Meanwhile, the troopers of the 13th Cavalry, although lacking a unified command since Colonel Slocum had not yet returned from Deming, responded immediately to the attack. Soldiers swiftly smashed locks to break into the guardhouse, where their weapons had been stored in accordance with post regulations. The Machine Gun Troop scrambled to put their sophisticated but unreliable Benet-Mercier machine guns into operation.

Lieutenant James P. Castleman, Officer of the Day, left his quarters, narrowly avoided getting shot, shot his assailant, organized troops, and orchestrated a counterattack. He mobilized his own unit, Troop F, which had already been turned out and armed by his sergeant. He took command of other troopers whose commanders had not yet reached the battle scene. His force soon turned back the Villistas’ right flank, and he recaptured the Regimental Headquarters. He moved his force into Columbus, driving raiders from residential and business areas. He soon took command of the town’s main thoroughfare.

Another lieutenant, John Lucas, rushed from his bed and quarters barefoot because he could not find his boots in the darkness and bedlam. He mobilized his unit, the Machine Gun Troop. His managed to put their stubborn weapons into action. He sent another lieutenant, Horace Longfellow, with several troopers to protect the left flank. Lucas, still barefoot, turned command over to Captain Jens E. Stedje, who had just arrived. Lucas moved a force into the business district, where his troopers found the Villistas silhouetted against the flames of burning buildings. Castleman and Lucas had now caught the Villistas in a crossfire.

The post kitchen detail, already preparing the morning breakfast, counterattacked with boiling water, an ax and shotguns. The stable detail counterattacked with whatever weapons came to hand, with one trooper using a baseball bat to kill a raider.

More than an hour after the attack began, Colonel Slocum showed up, having returned from Deming. He took command. With the attack collapsing, the raiders withdrawing and El León cursing their retreat (and probably his unreliable spies), the Mexican bugler sounded “Recall,” triggering a full retreat, said Rakocy. Slocum posted troopers on Cootes Hill to fire on the fleeing raiders. With Slocum’s approval, Major Frank Tompkins led a force of troopers in pursuit of the Villistas across the border into Mexico, continuing to pick off Villistas. He called off the effort and returned to Columbus only after his men exhausted their ammunition, food and water.

During the battle, both sides paid a heavy toll.

The Aftermath

“Villa effected a successful escape,” said Braddy, “but at a relatively high price. He escaped personally untouched; well over a hundred of his muchachos, however, lay dead. He lost a good deal of the material and food he had pillaged at Columbus, as well as two prized machine guns and a substantial amount of small arms and ammunition. He also lost to his pursuers an uncounted number of horses…”

With bodies in the streets and buildings in smoldering ruins, Columbus and Camp Furlong surveyed their losses. Ten civilians and eight soldiers lay dead. Two civilians, four enlisted men and two officers suffered wounds. (The number of casualties varies depending on the account.) The heart of Columbus had been turned into blackened rubble.

The troopers found 67 dead Villistas “in the camp and town and burned the bodies [along with dead horses] the following day,” said Lieutenant Lucas in a quote from Rakocy’s book. “It is impossible to say what the Mexican casualties were, but they must have been heavy because the mesquite was full of them. Few of their wounded could have survived.” The 13th Cavalry also seized several prisoners, hanging them from the gallows.

The soldiers also discovered that many of the Villistas could scarcely be counted as hardened veterans of the Mexican conflict; they were 14- to 16-year-old kids.

Retribution

In retaliation for the attack, Black Jack Pershing marshaled the Pancho Villa Expedition, an armed force of 10,000 men, marching them 350 miles into Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa, intending to put a permanent stop to the raiding. For the first time in U. S. military history, Pershing capitalized on the emerging technology of aircraft and motorized vehicles. He set up the first U. S. military airfield just north of Columbus. According to the Air & Space Power Journal (Winter, 2002) he supplemented his expedition with eight aircraft, 10 trucks, an automobile and six motorcycles. He used Columbus and Camp Furlong as one of the major staging areas.

In a campaign that lasted for nearly a year, Pershing failed in his bid to capture Villa, El León, who took refuge in old and familiar sanctuaries in the rugged mountain ranges of northern Chihuahua. The military aircraft, with canvas-covered fuselages and wings and wooden propellers, failed in the hot desert environment and 10,000-foot sierras. The motorized vehicles largely failed on the rocky roads and horse trails of the region.

If his expedition fell short in Chihuahua, Pershing took home valuable lessons in the art of the new warfare. American mechanized warfare had its birth in Columbus, New Mexico, this isolated desert hamlet of 400 people.

Columbus Today

You can reach Columbus, now a National Historic Site, by driving south from Deming for 35 miles on State Highway 11, or by driving west from El Paso for 60 miles along the border on State Highway 9. On the El Paso-to-Columbus route, you will parallel the old EP&SW railroad bed, the identical route Pershing and U. S. troopers traveled between Fort Bliss and Camp Furlong.

At Columbus, you will find the Pancho Villa State Park, once the site of Camp Furlong, the post headquarters and Cootes Hill. It contains, as the New Mexico State Tourism Department says, “extensive historical exhibits which depict [the] raid…” It also has rambling Chihuahuan Desert botanical gardens, which produce spectacular spring wildflower displays in those seasons with favorable conditions. It has full-grown sycamore trees that sprang from seedlings donated by Mexico’s state of Chihuahua in a expression of friendship 50 years after the Pancho Villa raid. It has campsites for both tents and recreational vehicles. A recently-opened museum “contains a full-size replica Curtiss JN-3 ‘Jenny’ airplane used by the 1st Aero Squadron; a 1916 Dodge touring car, the type used by Pershing for a field office; historic artifacts; military weapons and ribbons. An armored tank stands as a sentinel outside the facility,” according to the Pancho Villa State Park Internet site. For additional information, contact the Pancho Villa State Park, visit the park’s Internet site

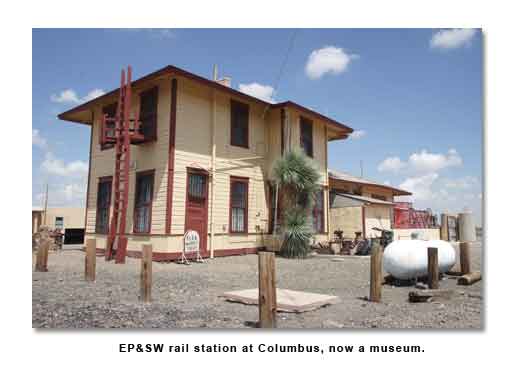

You will also find in Columbus the EP&SW railroad depot, now a museum that houses numerous period artifacts and an authentic Pancho Villa death mask, and you can still see several of the buildings that date from fearful night in March of 1916.

For additional information, contact:

The Pancho Villa State Park

P. O. Box 450

Columbus, New Mexico 88029

Phone 1-575-531-2711

Chamber of Commerce

Columbus, New Mexico 88029

Phone 1-575-531-2479

You should also make the three-mile drive south from Columbus to the border crossing, where you can park in a dirt parking lot and make the short walk over to Palomas, Chihuahua. (Check with the U. S. officials at the border before you cross to make certain you have the proper documentation for returning to the United States.) In Palomas, you will find a border treasure—La Tienda Roja, or The Pink Store, which has a tacky exterior, but inside, you can shop through a stunning array of the finest in arts and crafts from throughout Mexico, and you will discover a fine Mexican-food restaurant—charming, bright, cheerful, seasoned with live regional music.

Across the street, in a small community plaza, you will see a large statue of a dashing Pancho Villa, still a legendary figure celebrated in corridos and at fiestas. Immediately east of Tienda Roja, in a commercial plaza, you will see a life-size sculpture of Pancho Villa and Black Jack Pershing shaking hands, symbolizing a period of more peaceful times between our two nations.

![]()

El Paso's Mission Trail, and Then Some.

The Night Pat Garrett Shot Billy The Kid

Ghosts Of Old Mesilla

Ghost Towns and Desert Dreams

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms