Davis Mountains - Texas

Forts, Antelopes, and One Million Stars

Text and photos by George Oxford Miller

The old Sons of the Pioneers song, "Ghost Riders in the Sky," runs through my mind as we walk through the deserted rooms of the reconstructed Fort Davis. Behind the barracks, the volcanic slopes of the Davis Mountains rise precipitously from the parched desert floor. Lizards scamper over the broken rock walls, and sand burs sprout in the old parade grounds. Yet the rooms appear as though the soldiers just left on patrol.

Government issue wool blankets lie folded neatly on the bunks and empty wash basins sit on the tables. Along with the hazy light filtering through the narrow windows come the sounds of bugles and hoof beats and the clank and jangle of mounted troops. But no soldiers march past. Only the empty rooms and recorded sounds simulating the past remain.

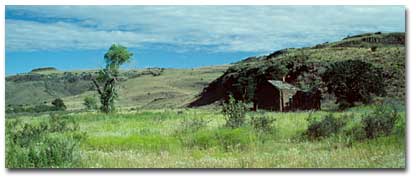

Besides a glimpse into yesteryear, the Davis Mountains of west Texas offer unexpected opportunities to experience both the natural beauty of the desert high plains and the cutting-edge of modern science. Hikers, bikers and wildlife watchers enjoy the mountain trails of Davis Mountain State Park and the scenic mountain loop drive. After seeing the beauties of the earth by day, visitors can catch a glimpse of the heavens by night at McDonald Observatory.

In the mid-1800s, an untamed wilderness stretched 600 miles west from San Antonio to El Paso. Mescalero Apaches lived near the present town of Fort Davis and irrigated their fields with water from the perennial streams of the mountains.

As settlers migrated from the heartland to California, wagon roads and stage routes penetrated the harsh desert. The hazardous trip through Texas took weeks by horseback through land ruled by some of the fiercest warriors to ever ride the Plains, the Apaches, who resisted the encroachment in a guerrilla warfare that gave no quarter.

To protect pioneers from the hostile inhabitants of the untamed territory, the military established a series of frontier forts. The first was Fort Davis, named after Jefferson Davis, the U. S. secretary of war and later president of the Confederacy. During the Civil War, the forts were abandoned and fell to ruins. After Appomattox, they were recommissioned and manned with buffalo soldiers, former slaves from the defeated South. Fort Davis stood at the strategic junction of heavily traveled passenger and freight trails across the desert.

In a winner-take-all war, the Federal troops defeated the Native Americans and by late in the nineteenth century, had driven them onto reservations. Today, Fort Davis is the finest example of the frontier forts that stretched across the West during that epic, nation-building era. Eighteen residences on officer's row, two troop barracks, a warehouse, and the hospital now stand as they originally did.

Hearing the real steps of a horse, I stepped out of the dim barracks into the bright sunlight and came face to face with a mounted cavalry officer in full battle regatta. But it wasn’t a trip into the Twilight Zone, just a costumed ranger adding to the feeling that somehow time has stopped in this still remote frontier settlement.

A trail behind the fort leads into a wooded canyon, up a steep hill, and into the 2,700-acre Davis Mountains State Park. The hiking trail meanders along ridge tops with vistas that stretch miles across desert grasslands to the distant mountains. The path follows Skyline Drive and leads into Keesey Canyon, in the heart of the park. The park encompasses both the desert grasslands (which attracted cattlemen to the area) and mountain slopes and jagged peaks. Woodpeckers nest in the blooming stalks of century plants, and barn swallows flit back and forth from their mud nests beneath the eaves of the local hotel. In the shaded, moist canyons, biologists have discovered rare plants and animals that would perish in the arid lower elevations. The endangered black hawk soars over the streams searching for its primary food, frogs. The Montezuma quail takes dust baths in the dirt roads of the campgrounds.

The Davis Mountains, with summits reaching 8,381 feet, are the most extensive mountain range wholly in Texas. One of the most scenic drives in Texas loops 74 miles through the mountains. The ranch land along the loop is the easiest place in the state to see the graceful pronghorn antelope. Herds of this once-abundant animal regularly graze within camera range of the highway. When alarmed, pronghorns, one of the fastest creatures in the world, can race away at speeds of 55 m.p.h.

The loop winds through wooded Madera Canyon and Limpia Creek, crosses grasslands, and passes the University of Texas McDonald Observatory, nestled atop the 6,791-foot Mount Locke. Built in 1932 with an 82-inch telescope, the observatory now probes the night skies with 107-inch reflector and 433-inch composite mirror telescopes as well.

The pure desert air, cloudless nights, and the absence of city lights make the Davis Mountains one of the darkest and most reliable viewing areas in North America. The observatory visitor center presents slide programs from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily, and it offers solar viewing in the mornings and afternoons and guided tours at 2:00 p.m. The gallery of the larger observation dome is open to the public for self-guided tours.

Those who want to peer into the heavens get the opportunity every Tuesday, Friday and Saturday at public "star parties." Telescopes set up at the visitor center focus on planets and stars. Visitors who make reservations, often necessary six months in advance, can attend once-a-month parties to gaze at celestial objects through one of the large telescopes.

The historic town of Fort Davis preserves the past, not to attract tourists, but because it has never had any reason to change. The Limpia Hotel, built in 1912, still has its turn-of-the-century oak furnishings, and the local drug store still serves old-time sundaes and malted-milk shakes. But one new addition attracts those interested in the beauty and ecology of the surrounding desert. The botanical gardens and nature trails of the 500-acre Chihuahuan Desert Visitor Center are the perfect place to see the blooming cactus and the unique plants and shrubs adapted to the arid climate.

Fort Davis is located 30 miles northwest of Alpine on TX 118. For more information, contact:

- Fort Davis Chamber of Commerce – 1-800-524-3015 or www.fortdavis.com.

- Fort Davis State Park – 1-915-426-3337

- Indian Lodge – 1-915-426-3254

- for all state park reservations – 1-512-389-8900

- Fort Davis National Historical Site – 1-915-426-3224.

- McDonald Observatory visiting times and star parties – 1-915-426-3640

There are resorts, hotels and motels in Van Horn, and nearby Alpine, TX with something for every taste and price range.

Related DesertUSA Pages

Other Places to Go in Texas

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms

SEARCH THIS SITE

View Video about The Black Widow Spider. The female black widow spider is the most venomous spider in North America, but it seldom causes death to humans, because it only injects a very small amount of poison when it bites. Click here to view video.

View Video about The Black Widow Spider. The female black widow spider is the most venomous spider in North America, but it seldom causes death to humans, because it only injects a very small amount of poison when it bites. Click here to view video.

The

Bobcat![]()

Despite its pussycat appearance when seen in repose, the bobcat is quite fierce

and is equipped to kill animals as large as deer. However, food habit studies

have shown bobcats subsist on a diet of rabbits, ground squirrels, mice, pocket

gophers and wood rats. Join us as we watch this sleepy bobcat show his teeth.

The Mountain

Lion

The Mountain Lion, also known as the Cougar, Panther or Puma, is the most widely

distributed cat in the Americas. It is unspotted -- tawny-colored above overlaid

with buff below. It has a small head and small, rounded, black-tipped ears. Watch

one in this video.

___________________________________

Take a look at our Animals index page to find information about all kinds of birds, snakes, mammals, spiders and more!

Click

here to see current

desert temperatures!