The Anza Trail

Juan Bautista De Anza

By Jay W. Sharp

On Monday morning, October 23, 1775, at the Royal Presidio of San Ignacio de Tubac, in what is today south central Arizona, Lieutenant Colonel Juan Bautista de Anza gave the command, "Everybody mount!" and his column of soldiers, vaqueros, muleteers, aids, servants and pioneers took to the saddle, ready to commence Spain’s first major expedition to settle California.

"…Mass having been chanted with all the solemnity possible on the Sunday preceding for the purpose of invoking the divine aid in this expedition, all its members being present; and the Most Holy Virgin of Guadalupe, under the advocation of her Immaculate Conception, the Prince Senor San Miguel, and San Francisco de Assis having been named as its protectors, at eleven today the march was begun…" Anza reported in his diary of the journey.

Anza would lead his column for 1200 miles and five and one-half months across the deserts of southwestern Arizona and southern California and up the coast of the Pacific Ocean through Alta, or Upper, California. He had been charged by Baylio Frey Don Antonio Maria Bucareli y Ursa – the viceroy, governor and captain-general of New Spain – to "better explore the country, and especially to conduct thirty families of married soldiers to the port of Monterey, in order by means of them to settle and hold the famous port of San Francisco," as Father Preacher Fray Pedro Font, the Franciscan chaplain of the expedition, explained in his diary.

The Trail Route

During the summer of 1775, Anza had recruited the pioneering families from desperately impoverished mixed-race settlements, mining camps, haciendas and presidios in the Spanish provinces of northwestern Mexico. As authorized and funded by the Spanish Crown, Anza promised the colonists two years salary, five years rations, camp gear, clothing, livestock and weapons, according to Virginia Marie Bouvier in her book Women and the Conquest of California, 1542-1840. From the final staging area, at the Tubac presidio, he would lead the column of 240, with approximately 1000 head of livestock, over a trail he had staked out earlier, in an exploratory expedition in 1774. Anza and the settlers began their journey to California with Fray Font’s alabado – a hymn in praise of God – ringing in their ears.

From Tubac, the trail led northward, following the Santa Cruz River to the Mission San Xavier del Bac, near the site where famed Jesuit Father Eusebio Kino undertook the Christianization of the Pima Indians in 1692. It turned northwest, continuing to follow the Santa Cruz River to its juncture with the Gila River. It headed westward, paralleling the Gila through the forbidding Sonoran Desert, to the juncture with the Colorado River and a ford near today’s Yuma, Arizona. After crossing the Colorado River, the trail continued toward the Pacific, dipping into Mexico’s state of Baja California. It turned northwest, across the farthest edge of the Sonoran Desert and through the southern reaches of California’s coastal mountain ranges. It then paralleled the Pacific shoreline and the coastal ranges north northwestward to the Royal Presidio of Monterey, passing the missions of San Gabriel Arcangel, San Luis Obispo de Tolosa and San Antonio de Padua, all founded by the Franciscans in the early 1770’s. The Monterey presidio would serve as the springboard for exploring both sides of San Francisco Bay and founding the city of San Francisco.

A Strategic Link

The Crown viewed Anza’s new trail as a strategic link to the northwest frontier of Spain’s American empire. The Spanish king, Carlos III, and Viceroy Bucareli hoped that the Anza Trail would serve as a reliable highway for conveying future pioneers and new supplies from communities in the northwestern provinces through Tubac to settlements and missions in Alta California. They knew that the alternative – resupply voyages by small sailing vessels through coastal waters from the provinces to California – came burdened with limited cargo and passenger capacities, dangerous winds and treacherous currents.

The Crown felt compelled to found and nourish California communities for several strategic reasons. Most immediately, settlements and missions would validate Spain’s claim to California’s west coast harbors, where Spanish galleons, laden with treasures from the Orient – an economic lifeline for the Crown – could find refuge after long and arduous voyages from the trading center of Manila, in the Philippines. The new communities would represent Spain’s response to the expansionist notions of Russia from the north and to the threats by French and English buccaneers from the open sea. They would position Spain to assert control over the fabled Northwest Passage, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, should such a watercourse ever be discovered. They would provide a base for pursuing the perpetual Spanish goal of enlisting the Indian peoples into allegiance with the Crown and the faith of Christianity.

The Pioneers

If King Carlos III and Viceroy Bucareli viewed new settlements in Alta California as instruments for projecting empire and religion, the pioneers themselves thought of the enterprise as an opportunity to improve their lives. Facing the anxieties of separation forever from their birthplaces and their parental kin, a long and punishing trek through an unknown land, and possible attacks by the Apaches, they followed Anza over his trail in pursuit of a common dream.

The 39-year-old Juan Bautista de Anza came well qualified for command. Born in Mexico into a Basque family with roots in north-central Spain, he had grown up on the northern frontier. Educated and trained, probably in Mexico City, he had dedicated his adult life to military service. He had fought against the Apache and Seri Indians. He had led an exploratory expedition of the western Sonoran Desert. He had helped the Franciscans found new missions among the desert tribes. He had won the respect of the Crown.

The seasoned Anza led a diverse party, including – according to his diary – expedition chaplain Pedro Font, Franciscan missionaries Francisco Garces and Thomas Eixarch, Lieutenant Don Joseph Joachin Moraga, Sergeant Juan Pablo Grijalva, 10 escort soldiers, 28 soldier/settlers, 29 soldiers’ wives (at least five of them pregnant when they left Tubac), 136 family members and volunteer settlers, 15 muleteers, 3 vaqueros, 5 interpreters, 4 personal servants, 3 missionary servants, and a commissary. Anza and a few soldiers had the pure blood of Spain flowing in their veins, but the rest of the party descended from Spanish and Indian, Spanish and African, or pure Indian parentage. Children, most of them 12 and under, made up well over half of the emigrants.

The expedition marched out of Tubac, Anza in the lead, with a flourish. The soldiers wore red government-issue military coats and carried festooned lances. The friars wore their order’s blue habits and leather sandals. The colonists, their children shouting in excitement, felt anticipation about their futures in California and, in the beginning, uncertainty about their places in the column. After a few days on the trail, the expedition would assume the characteristics of a movable village, with men, women, children and even livestock taking up customary places in the order of march and seeking out familiar neighbors in the nights of encampment.

"I may note," said Font, "that the order observed on the march during the whole journey was as follows: At a suitable hour an order was given to drive in the cavallada [the livestock], and that each one should proceed to catch his animals, the muleteers the mules, the soldiers and servants the horses for themselves and their wives and the rest. While they were being bridled and saddled it was my custom to say Mass, for which there was plenty of time. As soon as the pack trains were ready to start the commander would say, ‘Everybody mount.’ Thereupon we all mounted our horses and at once the march began, forming a train in this fashion: Ahead went four soldiers, as scouts to show the road. Leading the vanguard went the commander, and then I came. Behind me followed the people, men, women, and children, and the soldiers who went escorting and caring for their families. The lieutenant with the rear guard concluded the train. Behind him the pack mules usually followed; after them came the loose riding animals; and finally all the cattle, so that altogether they made up a very long procession." On the trail, the column typically traveled about one league, or roughly 2.6 miles, per hour.

According to his diary, Anza brought 220 horses and mules as mounts for the expedition; colonists brought another 120 mounts. Anza furnished 140 pack mules to transport camp gear, baggage, supplies, provisions, munitions and gifts (for the Indians); the colonists brought another 25 pack mules. Anza’s vaqueros drove 302 beef cattle, some to serve as provisions for the expedition, others, as seed stock for the new settlements. According to the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail Website!, Anza supplied 12 tents, including one for himself and his four servants, one for the three friars and their servants, and ten for soldiers, families and others. (In good weather, soldiers slept outside.) Anza gave the colonists clothing, probably more than many of them had ever seen. He brought six tons of food, including flour, beans, cornmeal, sugar and chocolate. The muleteers loaded the pack mules every day before the expedition took to the trail; they unloaded the animals every night.

If Anza took care of the pioneers’ material requirements, Friar Pedro Font took care of their spiritual needs. "I exhorted everybody to show perseverance and patience in the trials of so long a journey," he said in his diary, "saying they ought to consider themselves happy and fortunate that God had chosen them for such an enterprise… …I assured them the help of God and of our patroness, the Most Holy Virgin of Guadalupe, the host which would protect us during the whole journey if we conducted ourselves as good Christians."

Across the Desert

On October 23, 1775 the first night on the trail out of Tubac, Manuela Pincuelar, wife of 34-year-old soldier Jose Vicente Felix and mother of seven children, went into labor. "We aided her immediately with the shelter of a field tent and other things useful in the case and obtainable on the road, and she successfully gave birth to a very lusty boy at nine o’clock at night…" said Anza. Unfortunately, "the delivery was so irregular that the child was born feet first," said Font. "As a result," said Anza, "she was taken with paroxysms of death, and after the sacraments of penance and extreme unction had been administered to her, with the aid of the fathers who accompany us she rendered up her spirit at a quarter to four." Manuela’s death, coming at the outset, cast a gloomy skein across the expedition, but she would be the only one of the colonists to forfeit her life during the entire journey. Friar Garces escorted Manuela’s body to the Mission San Xavier del Bac, where he saw to her burial. Sorrowing, Jose Vicente Felix forged on with eight children, including his newborn infant, to begin a new life in California, without his wife.

On October 26, south of Tucson, Font commented in his diary that "It is a surprising thing that, although all this road traveled as far as here is very dangerous from the Apaches, they did not come out to attack us, nor did we see them during the whole journey," said Font. "This favor we ought to attribute to our patroness, the Most Holy Virgin of Guadalupe, because if the Apaches had sallied forth no doubt we should have suffered disasters, for the troops were few and green, and as they traveled they were so occupied with their little children that some of the soldiers carried two to three youngsters [with them on their saddle horses or mules] at a time, and most of them carried at least one little one…"

On October 31, southeast of the juncture of the Santa Cruz and Gila rivers, Anza declared a day of rest for his caravan. He and Fray Font, with a small party, including several Pima Indians, used the time to visit the remarkable prehistoric Puebloan ruin called Casa Grande de Moctezuma (Big House of Montezuma), which lay seven or eight miles to the southeast. "I decided to go see it for the purpose of making an observation of its latitude, as a notable site…" said Anza. "The house is rectangular," said Font, "and is perfectly oriented to the four cardinal points, east, west, north, and south. Round about there are some ruins which indicate some sort of fence or wall which enclosed the house and the other buildings, especially at the corners, where it appears that there was some sort of a structure like an interior castle or watch tower… The interior of the house consists of five rooms, three of the same size in the middle, and a larger one at each end… The thickness of the inner walls is four feet, and they are well plastered. The thickness of the outer walls is six feet…

"Judging from what can be seen the timbers were of pine, although the nearest mountain which has pines is distant some twenty-five leagues [approximately 65 miles]. There is also some mesquite. The whole edifice is built of earth..."

On the Gila River, at two in the morning of November 19, Ana Maria de Osuna, wife of soldier Ignacio Maria Gutierrez, and mother of two children under 12, went into labor. "I got up immediately to arrange that she be given assistance," said Anza, "wherewith she successfully gave birth to a boy, for which reason I suspended the march for today." Fort reported that, "After Mass I solemnly baptized the new born infant and named him Diego Pasqual, because it was the octave of the San Diego [the eighth day after the San Diego Feast Day] and because the place where we were was called San Pasqual…"

On November 30, at the Colorado River ford, near the Gila River junction, Anza, with the help of Yuma Indians who lived in nearby villages, prepared his expedition to ford the Colorado River at a location where the stream had divided into three branches. "…we began to cross the first branch of the river on the largest and strongest horses, leading by the bridles those on which the women and children were riding; and as a precaution, in case any one should fall, I stationed in front ten men on the downstream side," said Anza. "…the water reached nearly to the backs of the horses," said Font, "and even though they were tall, as mine was, nevertheless I got wet clear up to my knees." Anza said, "…we had no other mishap than the falling of a man who was carrying a child, but he was rescued immediately." Font said, "Father Garces was carried over on the shoulders of three Yumas, two at his head and one at his feet, he lying stretched out face up as though he were dead."

Yuha Desert from the De Anza Overlook

Anza held the column on the west side of the Colorado River for several days, building a shelter for the missionaries, Francisco Garces and Thomas Eixarch, who would remain in the area to minister to the Yumas. Meanwhile, several of the colonists had fallen so ill that a friar, presumably Font, administered the sacrament of penance to them. Fortunately, all would recover. On December 4, Anza continued the march, now approaching the most punishing passage of the entire journey, a route which would take the column away from the Colorado River through the desert sands of southern California to the westernmost edge of the Sonoran Desert.

On the route between the Colorado River and the Santa Rosa Mountains, just west of the Salton Sea and just east of today’s Anza Borrego Desert State Park, Anza knew, from his earlier exploration, that his soldiers would have to coax water from the desert by digging seep holes into dry stream beds. He knew that the holes would fill too slowly to meet the needs for the entire column on the same day. As he indicated in his diary, he knew that he would have to "make the march in [three] divisions on different days, in order to get enough water for all… The cattle, likewise, will have to make two marches without water…"

On December 9, the divisions began their treks, on succeeding days, just as the weather turned fiercely cold (a phenomenon of the "Little Ice Age," which lasted from the mid 15th century through the mid 19th century.) "…the sierras through which we had to travel were more deeply covered with snow than we had ever imagined would be the case," said Anza. The weather "had been very hard on our people, especially the women and children…" He fretted as the second and third divisions met delays on account of the storm. "…several persons were frozen, one of them so badly that in order to save his life it was necessary to bundle him up for two hours between four fires," he said. "…several persons were frozen to the point of being in danger of death."

Finally, on December 17, the divisions rejoined at a campsite on San Felipe Creek, between the southern Salton Sea and the Anza Borrego Desert State Park. Although the expedition lost numerous livestock to exhaustion, starvation and thirst, not a single person forfeited his life. Indeed, several who had been ill recovered during the march. "…may God be thanked," said Font. That night at the campsite on San Felipe Creek "with the joy at the arrival of all the people, they held a fandango [a jubilant Andalusian-style dance and feast]," said Font. To the exasperation of the friar, who was sick and ill tempered for most of the journey, the colonists celebrated the bawdy sings of Maria Feliciana Arballo, a spirited woman, recently widowed, who came on the expedition with her six- and eight-year-old girls to find new opportunity in California. The fandango, said Font, "was somewhat discordant, and a very bold widow who came with the expedition sang some verses which were not at all nice, applauded and cheered by all the crowd." At his next Mass, Font scolded the colonists for their behavior.

The next morning, Anza ordered his expedition back to the trail, heading generally northwest, across the heart of today’s Anza Borrego Desert State Park. For a week, his colonists, their morale sinking, would continue to suffer from intense cold. The livestock, failing rapidly as a result of exhaustion, hunger, thirst and the frigid weather, continued to collapse and die.

Christmas Eve found the colonists toiling up a fissure called Coyote Canyon toward a mountain pass. They came to the location of the villages of Indians known as "Los Danzantes" (The Dancers), northwest of the Anza Borrego Desert State Park. They must have felt that they had entered a surrealistic landscape.

"…all the country is sandy and stony," said Font. "The hills which form the canyon come to be like mountains of rocks, or boulders of all sizes, like stones which are found in the rivers, with some sand or dry earth, and so no one sees in them either trees or anything of value."

"Although from seven o’clock in the morning until two in the afternoon it had been cloudy, with a fog so dense that one could hardly see anything twelve yards away," said Anza, "several heathen…allowed themselves to be seen by us on the march."

"Near a spring, said Font, "we saw a village of Indians perched in the crags, from which they watched us pass…"

Near another spring, where the column would encamp, "…we saw another village whose houses were some half subterranean grottoes formed among the rocks and partly covered with branches and earth, like rabbit warrens. The Indians came out of their grottoes as if they were angry, motioning to us with the hand that we must not go forward, talking in jargon with great rapidity, slapping their thighs, jumping like wild goats and with similar movements, for which reason since [Anza’s 1774 exploratory expedition] they have been called The Dancers."

Entrance to Coyote Canyon in Anza Borrego Desert State Park

At this point, Anza felt compelled to call a halt to the march. A woman named Maria Gertrudis Rivas "was taken with childbirth pains." She could go no farther. Concerned about her condition, her husband, Ignacio Linares, or friends, summoned Font to confess Maria. "She was very fearful of dying," Font said, "but having consoled her and encouraged her as best I could I returned to my tent, and at half past eleven at night she very happily and quickly gave birth to a boy," who was named Salvador Ignacio Linares, the third child born since the expedition left Tubac. (Two women suffered miscarriages.) Salvador would join four siblings, one through seven, on the trail, and he would become known as "The Christmas Babe."

Meanwhile, in a soldier’s celebration of the season and a commander’s solution to fading morale, Anza produced a keg of brandy for the colonists, much to the dismay of Friar Font.

"Sir," Font said to Anza, "although my opinion is of no value and I do not cut any figure here, I can do no less than to tell you that I have learned that there is drinking today."

"Yes, there is," Anza replied, according to his diary.

"Well, Sir, I wish to say that does not seem to me right that we should celebrate the birth of the Infant Jesus with drunkenness."

"Father, I do not give it to them in order that they may get drunk."

"Clearly this would be the case because then the sin would be even greater, but if you know that they are sure to get drunk you should not give it to them."

"The king sends it for me and they deliver it to me in order that I may give it to the soldiers."

"This would be all right at the proper time. But I understand that to be in case of necessity."

"Well, Father, it is better that they should get drunk that to do some other things."

"But, Sir, drunkenness is a sin, and one who cooperates also sins, and so if you know that a person will get drunk on so much you should give him less, or none at all."

Font, in a huff, retired to his tent. At his next Mass, he scolded the colonists for their behavior.

The Promise of California

The day after Christmas, Anza ordered his column back to the trail. The new mother, Maria Gertrudis Rivas, he said, "was better and had the pluck to march…" He led the colonists up Coyote Canyon to the mountain pass called Puerto de San Carlos. With a light rain falling, he called a halt for the day. As darkness descended on the encampment, "distant thunder was heard," said Anza, "and this was followed by an earthquake which lasted four minutes"—a reminder, perhaps, of the tortuous desert passage which now lay behind the expedition.

The following day, Anza led the colonists down from the mountain pass, westward, where they began, at last, to see the promise of California. He said, "…we came out to level country with an abundance of the best pasturage, trees, and grass that we have seen thus far." He brought his column into the mission San Gabriel Arcangel, in the eastern part of today’s Los Angeles, on Thursday, January 4, 1776.

Over the next seven weeks, while the colonists rested and recuperated from the journey from Tubac, the tireless Anza, with several of his soldiers, helped put down an Indian rebellion at the San Diego de Pala mission, more than 100 miles to the south. He assigned a detachment to pursue and arrest several deserters, who stole more than two dozen mission and expedition saddle animals and fled east. He delegated several soldiers, with their families, to remain at San Gabriel Arcangel to bolster the mission. Finally, on February 21, he reassembled his movable village, now reduced to 17 soldier/settlers and their families, to take the trail northwestward, up the coast. It would become a late winter march over a muddy trail through almost continual rain and fog.

"I pronounced the blessing with ashes and said Mass, and in it spoke a few words to the people who were remaining and to those who were going, for some of them wept…" said Font. "We set out from the mission of San Gabriel at half past eleven in the morning," said Font, "and at half past four in the afternoon we halted… The land was very green and flower-strewn."

Anza led the column steadily northwestward, through California’s spectacular mountain sierra country, pausing at the missions of San Luis Obispo de Tolosa and San Antonio de Padua. "The welcome which they gave us [at San Luis Obispo]," said Anza "corresponded to their pleasure, and was such as may be imagined with people who spend all the days of their years without seeing any other faces than the twelve or thirteen to which most of these establishments are reduced…"

Anza led his caravan, wet from a downpour, into the area of the Royal Presidio of Monterey – the destination of the expedition – at four o’clock in the afternoon of March 10, 1776. "In all these days of travel," he said, "we have had no losses among the people whom I have conducted except the woman mentioned as having died of childbirth on the first night after we set forth from Tubac. Other adversities experienced and related herein are those common to roads less extended and more open…" Font said, "When we arrived at the presidio everybody was overjoyed, in spite of the fact that we were so wet, for we did not have a dry garment. We were welcomed by three volleys of the artillery, consisting of some small cannons that are there, and the firing of muskets by the soldiers." Soon four friars from the nearby Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo at Monterey came to welcome Anza and the colonists.

The Site of San Francisco

Having led the colonists to Monterey, Anza now began preparations for exploring the land around the Bay Area and choosing a site for San Francisco, but on March 13, during a visit to the Monterey mission, he collapsed with a sudden illness, which rendered him bedfast, feverish, scarcely able to move, for more than a week. He had been "attacked by some very severe and sharp pains in the groin, the hip, the knee, and the left thigh, which had been so violent that I could not breathe and I have thought I should be suffocated and die," he said.

Finally, on March 23, a recuperating Anza, with Lieutenant Moraga, Friar Font and 11 soldiers, embarked on their mission of exploration. He marched up the east side of San Francisco Bay to the location of today’s Fort Point, near the south end of the Golden Gate Bridge. "I beheld," said Font, "a prodigy of nature, which is not easy to describe… We saw the spouting of young whales, a line of dolphins or tunas, besides seals and otters… This place and its surrounding country afforded much pasturage, sufficient firewood, and good water, favorable conditions for establishing the presidio or fort contemplated…"

"There I set up a cross," said Anza, "and at its foot I buried under the ground a notice of what I have seen."

"…the cross was erected on a place high enough so that it could be seen from all the entry of the port and from a long distance away…" said Font.

"…I think that if it could be well settled like Europe there would not be anything more beautiful in all the world, for it has the best advantages for founding it in a most beautiful city…"

Anza had chosen the site for the future city of San Francisco. It was March 28, 1776.

The End of the March

Over the next several days, Anza and his party explored the east side of San Francisco Bay then returned to the presidio at Monterey. He had completed his work. He knew the time had come for him to go home. "Senor Anza finished arranging matters relating to the delivery and the accounts of his expedition and after dinner most of the people whom we had brought came to say goodbye, with not a few tears on account of the love which they had come to feel for us." Friendships forged during the shared hardships of the trail were receding into memory. "I began my return," on April 14, 1776, said Anza, "with Father Fray Pedro Font, seven soldiers of my command…; the commissary who came with the expedition; six muleteers…; two of the three cowboys who came…; and four of my servants."

"The pack train consisted of nineteen loads," said Font, "three of which were for the mission of San Antonio. And in a cage we carried… four cats, two for San Gabriel and two for San Diego, at the request of the fathers, who urgently asked us for them, since they are very welcome there on account of the great abundance of mice..."

The Anza Trail would answer its purpose as a highway for conveying pioneers and supplies from communities in the northwestern provinces through Tubac to settlements and missions in Alta California for five years, long enough for the Spanish to establish firm roots, then the Yuma Indians revolted, shutting down the trail for the remainder of the colonial period.

Whatever Happened to…?

We have a fair amount of information about what happened to Juan Bautista de Anza after his return from Alta California. We know far less about what happened to Father Fray Pedro Font.

Thanks to Zoeth Skinner Eldredge and his work, The Beginning of San Francisco, published in 1912 and now available through the internet, we have at least broad outlines about some of the settlers who followed Anza up the trail from Tubac to California. They all left their signature on the history of the state. Some highlights are as follows:

Juan Bautista de Anza – After his return from the long trek, Anza served as governor of New Mexico, led new expeditions in the northern frontier, commanded campaigns against the Comanches, negotiated enduring treaties with the Comanches and other tribes, and served in command posts in Sonora.

Father Fray Pedro Font – At loose ends after his return, a restless Fray Font settled at the mission at Tubutama, in northern Sonora, "without any special occupation or destination," he said, and he turned to the work of expanding his chronicle of the expedition.

Jose Joaquin Moraga, Lieutenant – Following the departure of Anza, Moraga assumed command of the colonization of California, founding the mission and presidio of San Francisco, the mission of Santa Clara, and the pueblo of San Jose. He became an honored and respected officer. His descendants owned property in Contra Costa County, east of the Bay Area, into modern times.

Juan Pablo Grijalva, Sergeant – Grijalva retired in 1796 after a distinguished career in the Spanish military. His descendants received major land grants in California and stamped the name "Grijalva" prominently in the state’s history.

Jose Vicente Felix, Soldier/Settler – Felix, the soldier whose wife, Manuela Pincuelar, died in childbirth the first night on the trail out of Tubac, settled in southern California with his eight children. He would receive a large land grant in California – the Felix rancho – just north of a small pueblo known as Los Angeles.

Gabriel Peralta, Soldier/Settler – Peralta, who served in the military for 45 years, until 1826, received one of the most valuable of all the land grants in California. It encompassed the area directly across the bay from San Francisco—the sites of Oakland, Alameda and Berkeley.

Juan Salvio Pacheco, Soldier/Settler – Although he died in the year following his arrival in California, his five children produced a number of descendants who received several major land grants. He gave his name to the community of Pacheco, in northern Contra Costa County.

Ignacio de Soto, Soldier/Settler – He and his wife, Maria Barbara Espinosa de Lugo, became the parents of the first child of European heritage born in San Francisco. The child, a son named Francisco Jose de los Dolores Soto, served with distinction in the military for many years, becoming recognized as a great Indian fighter. His descendants received a number of land grants in California.

Jose Antonio Sanchez, Soldier/Settler – Sanchez’ son, also named Jose Antonio, a distinguished military officer, a major land grant holder, a farmer and a religious rebel, propelled his family to prominence in San Francisco during the first half of the 19th century. His son (the pioneer Jose Antonio Sanchez’ grandson) also became a distinguished military officer.

Santiago de la Cruz Pico, Soldier/Settler – He founded a large family which played prominent roles in the California military and politics. His descendants served as top officers in California’s Spanish and Mexican armed forces. They commanded California forces in various military engagements. They held appointed and elected political position at the state level. His grandson, Pio Pico, served as the last Mexican governor of California.

Maria Feliciana Arballo, Private Citizen – Arballo, the widow who sang bawdy songs and embarrassed Fray Font at the campsite on San Felipe Creek, quit the expedition at San Gabriel to marry a soldier named Juan Francisco Lopez. Her daughter, Maria Estaquia, who had traveled over the entire trail with Arballo, married a son of Santiago de la Cruz Pico and gave birth to Pio Pico, the governor. Arballo’s daughter, Maria Ignacia Lopez de Carrillo, by Juan Francisco Lopez, lies buried in the ruins of the San Francisco Solano mission at Sonoma, beneath the original location of the font, where holy water streaming from the hands of the devout once fell on her grave.

Exploring the Anza Trail

Should you follow Juan Bautista de Anza’s route from Tubac to Alta California – now a National Historic Trail – you will be richly rewarded in terms of the diversity of the landscape and the span of the human experience. You will travel through a stark desert, across forested mountain slopes, and beside crashing coastal waters. You will not only see presidios and missions which symbolize Spain’s last great reach for colonial empire in the Americas, but also the ruins of a city built by people who disappeared long before the Spain staked her claims in the Southwest. You will see, at the northern end of Anza’s Trail, the fulfillment of Font’s vision of "a most beautiful city."

Tubac – If you begin your journey at the trailhead, at Tubac, about 45 miles south of Tucson, now a state historic park just off Interstate Highway 19, you can explore a visitor center, the presidio ruins, an underground archaeological exhibit and historic buildings. Originally, the Pima Indians had built a small village at the site. The Jesuit priest Eusebio Francisco Kino established a mission and farming enterprise there in 1691. Spanish colonists began settling in the area in the 1730’s. Before you head north up the Anza Trail, you might drive a few miles south on IH 19 to visit the National Historical Park, Tumacacori, where Kino established missions late in the 17th century. Today, it features a mission church built by the Franciscans early in the 19th century.

San Xavier del Bac Mission – You will find the still-active San Xavier del Bac Mission about 45 miles north of Tubac, just east of IH 19, about nine miles before you reach Tucson. It is here that Manuela Pincuelar, the expedition woman who died in childbirth, lies buried. The two-century-old, dazzling white chapel, with its richly textured Spanish mission-style exterior and interior, emerged from a long period of decay as a sparkling crystal in the desert. You may join pilgrims and art students in examining the church’s adorned facade, frescoed interior, and numerous shrines. You can also see displays of historic vestments, ceramics and documents in the museum. You can attend one of the daily Masses and, with good timing, one of the church’s fiestas.

Casa Grande – Some 65 miles northwest of Tucson, off IH 10, you will come to the National Monument, Casa Grande, the 14th century Puebloan ruin visited by Anza, Font and several other expedition members in a side trip on October 31, 1775. The dominant building, a 60-foot by 40-foot four-story earthen structure shielded from weather and erosion by a modern metal canopy, may have served as a prehistoric observatory. The Puebloan builders not only aligned the outer walls with the cardinal directions, they also aligned windows and viewing ports with annual solar and lunar events. In the 14th century, Casa Grande was one of several pueblos built near the Gila River and linked by a lengthy irrigation network.

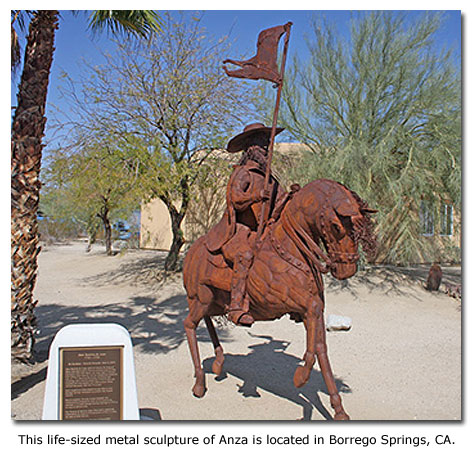

Anza Borrego Desert State Park – When you reach southern California’s 600,000-acre Anza Borrego Desert State Park, where Anza’s expedition suffered through one of the intensely cold storms born of the Little Ice Age, you will be greeted by a stunning kaleidoscope of desert and mountain vistas, geologic formations, wildlife, native plant communities and prehistoric archaeological sites. You can explore desert basins which lie below the level of the sea or sierras which reach nearly 9000 feet above the level of the sea. At the outset, you should go by the visitor center, just west of the community of Borrego Springs, for an orientation. You will have a number of options from which to choose. ("Borrego," incidentally, is the Spanish word for fleecy white clouds.) If winter was perhaps the worst time to visit Anza Borrego Desert State Park in Anza’s time, it is now the best.

The Missions – As you put the desert behind you, heading northwest for Los Angeles and the Pacific coastline, you can still the visit the three Franciscan missions which the Anza expedition passed en route to the Monterey area. The San Gabriel Mission, located on the eastern side of Los Angeles, gave rise to the founding of the city. It has an extraordinary collection of mission relics, including six invaluable Spanish altar statues. The San Luis Obispo de Tolosa Mission, in downtown San Luis Obispo, forfeited its lands and collapsed into rubble in the wake of Spain’s defeat at the hands of her rebellious colony, Mexico, in 1821. Restored as a parish church, with the original priest’s quarters converted into a museum, the mission is today one of the most beautiful in the state. The San Antonio de Padua Mission, about five miles west northwest of Jolon, signified the realization of the Franciscan vision of a "chain of missions" up through Alta California. The most isolated of all the 21 California missions, San Antonio fell into disuse and ruin for nearly 50 years, until well into the 20th century, when the Hearst Foundation and the California Franciscan Order funded the restoration. The San Gabriel, the San Luis Obispo and the San Antonio missions – along with 18 other missions – give expression to the Spanish legacy in today’s California.

The Royal Presidio and the Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo – At the charming city of Monterey, you can visit the Royal Presidio site, where Anza delivered his colonists on that rainy afternoon of March 11, 1776. The Royal Chapel – the only structure of the original complex still standing – has been in continuous service since its construction in 1794. It is now a Registered National Historic Landmark. At Carmel-by-the-Sea, a few miles south of the presidio site, you will find the mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, beautifully restored after it collapsed into rubble during the 19th century. Its Moorish-style architecture, formal gardens, open courtyard, museum and early friars’ graves memorialize the Spanish heritage of its founders. Its cemetery for mission Indians, located beside the church, with graves blanketed by vines, testifies to the number of Indians converted to Christianity by the Franciscan fathers.

The San Francisco Presidio – In San Francisco, at the south end of Golden Gate Bridge, you can see the land and water that Friar Font called a "prodigy of nature," and you can see that elegant, arching golden bridge that he might today call a "prodigy of engineering." You can visit the site where Spanish soldiers, under Lieutenant Moraga, returned to begin construction of the San Francisco Presidio after Anza had chosen the location. Anza could scarcely have known that the presidio would become a strategic location for the defense of the west coast of the United States into modern times. Now part of the Golden Gate National Recreation area, the presidio has a visitor center and museum with exhibits and illustrations covering Spanish, Mexican and United States uses of the sites, and it provides walking trails through what became the main post of the presidio during U. S. occupation. It was here that San Francisco took root.

Following the Anza Trail today, you will cross or skirt a galaxy of other federal, state, regional and local parks, recreation areas, monuments and historic sites. You will find the route and campsites of the expedition marked in many areas. You will experience one of the great travel adventures in America.

Sources

If you want a good overview, you will find that the University of Oregon Center for Advanced Technology in Education site Web de Anza Resources offers excellent summary information, maps, trail data, illustrations, and primary and collateral source material. If you want to become a scholar, you would start with that wellspring of information: H. E. Bolton’s five-volume set which he called, collectively, Anza’s California Expeditions, where he published scholarly, but highly readable, translations of diaries and correspondence from the expedition. Z. S. Eldredge’s The Beginnings of San Francisco From the Expedition of Anza, 1774 to the City Charter of April 15, 1850, which has been posted on the internet, also gives a good account of the expedition.

More Trails

Desert Trails

Trails of the Native Americans

Coronado Expedition from Compostela to Cibola

Coronado Expedition from Cibola to Quivira then Home

Chihuahua Trail

Chihuahua Trail 2

Jornada del Muerto Trail

Santa Fe Trail

The Long Walk Trail of the Navajos

The Desert Route to California

Bradshaw's Desert Trail to Gold

A Soldier's View of the Trails Part 1

A Soldier's View of the Trails Part 2

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms