Chihuahua Trail

Part 1 of the Chihuahua Trail

The Chihuahua Trail – a millennia-old corridor for human passage across the northern Chihuahuan Desert to the Southern Rocky Mountains – ranks among the most historic highways in North America. It has served as an avenue for commerce, conquest, warfare, migration, adventure, flight and ideological change.

The Trail Route

Some 550 miles long, the trail connects Chihuahua, the capital of Mexico’s state of Chihuahua, with Santa Fe, the capital of the U. S. state of New Mexico. It devolved, during the 18th and 19th centuries, from the northern segment of the main artery of the old 1500-mile-long Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (the Royal Road of the Interior Land), a Spanish roadway which began at Mexico City and ended in northern New Mexico.

Historically, the south end of the Chihuahua Trail segment began near Chihuahua’s central plaza, at the front of the city’s large baroque-style cathedral. According to Max L. Moorhead in his New Mexico’s Royal Road: Trade and Travel on the Chihuahua Trail, it led northward for some 50 miles through an open desert valley, between a range of hills on the east and the Sierra de Nido (Shelter Mountains) on the west. It crossed the small, but historic, Sacramento River about 20 miles north of Chihuahua. It passed the Laguna Encinillas (Live Oak Lake), a shallow playa lake fed by springs and intermittent streams, at the northern end of the valley. It continued northward for more than 100 miles through basin and range country, reaching the 770-square-mile Samalayuca sand dune field just north of Laguna Patos (Duck Lake). Here, the trail split. One branch proceeded due north for some 60 miles, through the towering dunes then across desert brushlands, to a ford of the Rio Grande and the famous pass between the Juarez and Franklin mountain ranges—now the site of the border cities Juarez and El Paso. The other branch veered northeast for roughly 45 miles, across the dune field’s southeastern margin, to the south bank of the river. It followed the Rio Grande upstream some 35 miles to Juarez and El Paso and the ford—often called simply, "The Pass." Today, the original trail (except for the branch which skirted the Samalayuca sand dunes) from Chihuahua to The Pass lies beneath or beside Mexico’s Federal Highway 45.

Chihuahua’s central plaza, at the front of the city’s large baroque-style cathedral. According to Max L. Moorhead in his New Mexico’s Royal Road: Trade and Travel on the Chihuahua Trail, it led northward for some 50 miles through an open desert valley, between a range of hills on the east and the Sierra de Nido (Shelter Mountains) on the west. It crossed the small, but historic, Sacramento River about 20 miles north of Chihuahua. It passed the Laguna Encinillas (Live Oak Lake), a shallow playa lake fed by springs and intermittent streams, at the northern end of the valley. It continued northward for more than 100 miles through basin and range country, reaching the 770-square-mile Samalayuca sand dune field just north of Laguna Patos (Duck Lake). Here, the trail split. One branch proceeded due north for some 60 miles, through the towering dunes then across desert brushlands, to a ford of the Rio Grande and the famous pass between the Juarez and Franklin mountain ranges—now the site of the border cities Juarez and El Paso. The other branch veered northeast for roughly 45 miles, across the dune field’s southeastern margin, to the south bank of the river. It followed the Rio Grande upstream some 35 miles to Juarez and El Paso and the ford—often called simply, "The Pass." Today, the original trail (except for the branch which skirted the Samalayuca sand dunes) from Chihuahua to The Pass lies beneath or beside Mexico’s Federal Highway 45.

After crossing The Pass, which became a focal point for settlement, commerce, transportation and the military post Fort Bliss, the trail bore northward, up the Rio Grande valley for some 55 miles. It passed the Franklin and Organ mountain ranges to the east. Just north of the small range called the Robledo Mountains, on the west side of the valley, the trail veered away from the river, which followed a westward-bending arc through a heavily dissected landscape before it resumed its north/south course. The trail itself "strung the bow," intercepting both ends of the river’s arc. The 90-mile segment, which lay east of the Caballo and Fra Cristobal ranges and lacked any dependable sources of water, became known as the "Jornada del Muerto," the "march of the dead," or "dead man’s journey." It became the most notorious and fearful passage in the entire Chihuahua Trail. Rejoining the river, the trail followed the valley northward for 150 miles, through the region of the historic pueblos which greeted Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century. It passed at the foot of that brooding, lava-capped mesa called "Contadero." It skirted the western edge of a sprawling and biologically rich marshland called the "Bosque del Apache." Hewing to the Rio Grande, it passed Albuquerque and the western flanks of Manzano and Sandia mountain ranges, then it began the ascent from the desert or, the Rio Abajo, or the Lower River, to the Southern Rocky Mountain foothills, and the Rio Arriba, or the Upper River. At the San Domingo Pueblo, the trail veered away from the Rio Grande again, following its Canada de Santa Fe tributary for roughly 30 miles into the community of Santa Fe and the main plaza, the north end of the trail, which stood surrounded by single story adobe buildings. Today, with the exception of the Jornada del Muerto passage, the corridor parallels Interstate Highway 10 from El Paso to Las Cruces and IH 25 from Las Cruces to Santa Fe.

The Chihuahua Trail’s near coincidence with modern highways, both in Mexico and the United States, speaks to the route’s natural and historic place as a roadway for human travel.

The History

For many centuries before the Spanish arrived, Indian nomads moved up and down the Chihuahua Trail to hunt game and gather useful plants, leaving the records of their presence at small campsites marked by the charcoal of fire hearths, tools of stone and animal bone, and projectile points of flint and chert. Indian traders trekked up and down the route to establish and sustain a commercial and ideological connection between the great city states of southern Mexico, or Mesoamerica, and the village farmers of the Rio Grande drainage basin. They left the evidence of their passage – macaw remains, copper bells and saltwater shells from the south and turquoise, exotic minerals and animal hides from the north – at communities along the trail. They left the imprint of their beliefs and world view in the minds and spirituality of the village farmers, who chiseled and painted Mesoamerican-style images of deities and symbols on the surfaces of stone at sacred sites beside the trail, for instance, at San Diego Mountain, a few miles upstream from the Robledo range, and at Petroglyph National Monument, on the Rio Grande’s western escarpment across from Albuquerque.

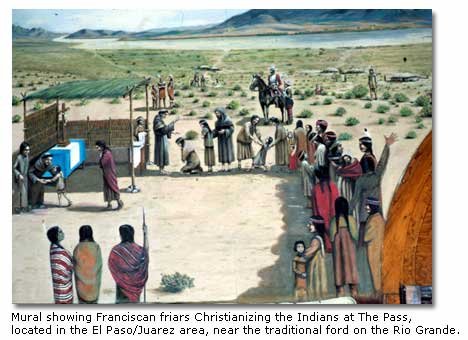

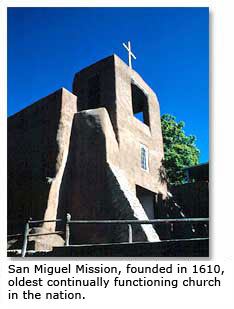

The Spanish discovered the trail in the 16th century. In the winters of 1540/1541 and 1541/1542, General Francisco Vasquez de Coronado and his officers explored the corridor from the northern end of the Jornada del Muerto upstream into the Southern Rocky Mountain range, visiting pueblos scattered along the Rio Grande and its tributaries. In 1581, Captain Francisco Sanchez Chamuscado led a vanguard expedition over part of the trail between The Pass and the northern pueblos in a fruitless endeavor to establish missions and trade. In 1582 and 1583, wealthy businessman Antonio de Espejo led an expedition over part of the trail to check on the welfare of Franciscan friars who had left the Chamuscado expedition to begin the work of the Church among the pueblos. He arrived too late. The unwelcome missionaries had forfeited their lives. In 1590 and 1593, renegade Spanish expeditions traveled segments of the trail in abortive attempts to found colonies. Finally, in 1598, in a royally endorsed enterprise which promised new estates and possible valuable mineral deposits for enterprising Spaniards and new conversions for the Church, Don Juan de Onate led a major colonizing expedition up the full length of the trail. With approximately 400 settlers, 80 carretas (two-wheeled, hand-hewn wooden freight wagons), two heavy carriages and 7000 livestock, he established the first Southwestern European settlement near Espanola. A decade later, the Spanish abandoned the settlement, moved south and founded Santa Fe. In the summer of 1680, more than 2000 Spanish survivors of a bloody Puebloan revolt – triggered by the colonists’ notions of conquest, entitlements, culture and Catholicism – fled down the trail to refuge near The Pass. They left behind more than 400 dead, including 21 Franciscan priests, in the pueblos, settlements and haciendas of the upper Rio Grande. Twelve years later, the Spanish marched back up the trail to reclaim the land and establish an enduring presence. For the next century, the Spanish sent caravans of settlers, supplies and merchandise up the trail and into the pueblo country every few years. Nourished by the trail, the Hispanic colonies, with a total population growing to 25,000, tightened their grip on the Puebloan people, body and soul. For miles along the trail, they founded new communities, appropriated farm lands, promoted the Church and conscripted the Puebloan and other Indian peoples. They created a new, Hispanic/Indian society – in effect, a sub-nation within the Spanish empire – with deep roots in the soil. Early in the 19th century, they heard, from explorers such as Zebulon M. Pike, the siren call of promising new trading opportunities with the brawny young nation to their east.

In 1821, Mexico overthrew three centuries of Spanish rule, and within months, U. S. traders forged a link between the Chihuahua Trail and a brand new route, the Santa Fe Trail. In coming years, they would use the two connected trails as a conduit for moving trade goods from Missouri to Santa Fe to Chihuahua. According to Josiah Gregg in his classic The Commerce of the Prairies, U. S. and Hispanic traders transported some $9000 worth of merchandise south over the Chihuahua Trail in 1822. Even though they faced formidable challenges from the Apaches, especially on the Jornada del Muerto, they increased the trade over the Chihuahua Trail tenfold within the next two decades. The commerce became so lucrative that Texas sent a military expedition to New Mexico in 1841 – the Texas Santa Fe Expedition – purportedly for the purpose of establishing trade but with the sub rosa intention of annexing the territory and co-opting the trade. It failed. The Mexicans took the Texans captive and sent them down the Chihuahua Trail to prison in Mexico.

Meanwhile, the United States and Mexico, disputing claims to a territory which extended from the Piney Woods of eastern Texas to the shores of the Pacific Ocean, went to war. A U. S. force marched into Santa Fe unopposed on August 18, 1846, asserting control over the upper Rio Grande region. While one part of the force stayed in Santa Fe to impose order and a second part headed to the west to conquer California, a third part, under Colonel Alexander William Doniphan, marched down the Chihuahua Trail to capture Chihuahua. Doniphan engaged and defeated Mexican troops at El Brazito, about 25 miles up the Rio Grand from The Pass, and he engaged and defeated another Mexico force near the Sacramento River trail crossing, 20 miles north of the city of Chihuahua. When the war ended, on February 2, 1848, the U. S. had won all of Texas and most of the Southwest—nearly half the total territory which had previously been claimed by Mexico. In 1854, under an agreement negotiated by John Gadsden in Mesilla, a Chihuahua Trail community about 45 miles north of The Pass, the U. S. purchased a 30,000-square-mile strip of land which became today’s southwestern New Mexico and southern Arizona.

Ocean, went to war. A U. S. force marched into Santa Fe unopposed on August 18, 1846, asserting control over the upper Rio Grande region. While one part of the force stayed in Santa Fe to impose order and a second part headed to the west to conquer California, a third part, under Colonel Alexander William Doniphan, marched down the Chihuahua Trail to capture Chihuahua. Doniphan engaged and defeated Mexican troops at El Brazito, about 25 miles up the Rio Grand from The Pass, and he engaged and defeated another Mexico force near the Sacramento River trail crossing, 20 miles north of the city of Chihuahua. When the war ended, on February 2, 1848, the U. S. had won all of Texas and most of the Southwest—nearly half the total territory which had previously been claimed by Mexico. In 1854, under an agreement negotiated by John Gadsden in Mesilla, a Chihuahua Trail community about 45 miles north of The Pass, the U. S. purchased a 30,000-square-mile strip of land which became today’s southwestern New Mexico and southern Arizona.

As the U. S. asserted control of its vast new territory, it soon discovered that it had fallen heir to a major problem: relentless marauding by the Apaches and Navajos. The army began to establish a military presence on the Chihuahua Trail to protect civilian caravans and settlers from raids, posting garrisons and building forts at strategic locations. In 1851, troopers built Fort Fillmore, located about six miles south of Mesilla, on the eastern escarpment of the Rio Grande. In 1853, they built Fort Thorn near the southern end of the Jornada del Muerto, which had become infamous for raiding by Mescalero and Chiricahua Apaches. In 1854, they built Fort Craig, one of the largest 19th century forts in the Southwest, near the northern end of the Jornada del Muerto, just across the river from the Contadero Mesa.

A few years later, there arose a problem even more serious than Indian raiding: the American Civil War. The Confederates quickly saw the Chihuahua Trail as the linchpin for an ambitious campaign to extend the South’s empire to the Pacific Coast, open new lines of supply, recruit new sympathizers for the Southern cause, and win recognition from England and France. Late in 1861, Confederate Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley raised a force of Texans – "Sibley’s Brigade" – to march from San Antonio to the Rio Grande and The Pass, the site of Fort Bliss. He would then turn north, up the trail, to engage Union forces in New Mexico. He would use his triumphs on the Chihuahua Trail as a springboard to conquer the West. Before Sibley reached Fort Bliss, a small Confederate force, under Lieutenant Colonel John Robert Baylor, seized the village of Mesilla without opposition; fought off an attempt by Union soldiers to re-take Mesilla; and captured the entire garrison of Fort Fillmore in retreat near the Organ Mountains, a few miles east of the trail. After Sibley arrived at Fort Bliss, he moved his brigade up the Chihuahua Trail, winning a costly and bloody victory at Fort Craig, seizing Albuquerque and Santa Fe without opposition, and blundering into disaster at Glorieta Pass, in the Southern Rockies, east of Santa Fe. Sibley’s beaten brigade straggled piecemeal back down the Chihuahua Trail to Fort Bliss, with a third of the force dead, wounded, sick or captured. The Confederate campaign to conquer the Southwest and establish Pacific ports had failed.

Union forces again turned their attention to protecting the Chihuahua Trail from raids by the Apaches and Navajos. In 1862, the army assigned a garrison to guard Mesilla and neighboring communities. In 1863, Union soldiers built Fort McRae near a spring in the Fra Cristobal Mountains to protect travelers on the Jornada del Muerto. (Fort McRae now lies inundated by the waters of Elephant Butte Reservoir.) In 1865, soldiers built Fort Selden at the southern end of the Jornada del Muerto, replacing Fort Thorn, which the army had abandoned in 1862. (Captain Arthur MacArthur, accompanied by his wife and two young sons, Arthur and future famous general Douglas, served as commanding officer at Fort Seldon from 1884 to 1886.)

Union forces again turned their attention to protecting the Chihuahua Trail from raids by the Apaches and Navajos. In 1862, the army assigned a garrison to guard Mesilla and neighboring communities. In 1863, Union soldiers built Fort McRae near a spring in the Fra Cristobal Mountains to protect travelers on the Jornada del Muerto. (Fort McRae now lies inundated by the waters of Elephant Butte Reservoir.) In 1865, soldiers built Fort Selden at the southern end of the Jornada del Muerto, replacing Fort Thorn, which the army had abandoned in 1862. (Captain Arthur MacArthur, accompanied by his wife and two young sons, Arthur and future famous general Douglas, served as commanding officer at Fort Seldon from 1884 to 1886.)

In the years immediately following the Civil War conflicts, the army struggled to contain the Apaches. Traders, travelers and settlers continued to drive caravans of wagons over the Chihuahua Trail. In 1881, the railroad arrived, following a route closely parallel to the trail and signaling the end of vehicles drawn by oxen, mules, horses and burros. Today, we still travel the Chihuahua Trail, that corridor of human passage, but now in automobiles, trucks, trains and airplanes. In fact, as you fly up the Rio Grande from El Paso to Albuquerque by commercial airline, you can still see the trail left by the caravans on the Jornada del Muerto.

Trekkers and Caravans

Plausibly, the merchants on the route of the Chihuahua Trail a thousand years ago closely resembled the itinerant Indian traders on ancient Southwestern footpaths in historic times. Serving as middlemen, they trekked in families or small trading groups, carrying large burdens of commodities on their backs from village market to village market. They may have played flutes to announce their arrivals, which could have prompted welcoming celebrations. Likely, they departed their home villages after rituals intended to protect them on the trail. They returned to purification ceremonies aimed at purging them of the evil spirits of travel.

In colonial times, a Spanish caravan, which originated in Mexico City, would travel over the Chihuahua Trail to northern New Mexico every three or four years. Carefully and formally organized, it would spend nearly five months on the trail from Mexico City to Chihuahua City and another 40 days on the trail from Chihuahua City to Santa Fe. Usually, the caravan covered eight to 12 miles a day. It came north with new settlers who would join the colonies; brought missionaries and government officials who would take up new frontier postings; replenished supplies for the missions and settlements; and transported new merchandise for colonial markets. It returned south with missionaries and officials who had been relieved or reassigned. It hauled products and herded livestock which had been produced by the colonies for sale in Chihuahua and the more southern Mexican provinces. "Normally," said Moorhead, "the entire train consisted of thirty-two wagons and was organized into two sections which were further subdivided into detachments of eight wagons. Each of the two sections was under the supervision of a mayordomo, or wagonmaster, and the lead wagon of each of its detachments flew the royal banner." Nominally, a caravan transported 64 tons of freight, supplies, spare parts, tools, mail and baggage. Skilled wagoners, whose four-wheeled vehicles each had a capacity of two tons, commanded eight-mule teams. Herders drove alternate mule teams and spare animals for the wagons and beef cattle for the caravan larder. The trail all the way from Mexico City to Santa Fe was so rugged, said Douglas Preston in an article in the Smithsonian, November, 1995, that "A wagon that returned to Mexico City was not the same one that set out: almost everything had been replaced at least once." Soldiers, often garrisoned either at presidios or communities along the trail, escorted the caravans to protect them from Indian attacks, at least through the most dangerous jornadas. For decades, the caravans served as virtually the only link between the outposts of the frontier and the world of Mexico and Spain.

After the Mexican American War, U. S. merchants – free-wheeling entrepreneurs – accelerated their enterprises over the trail to capitalize on developing markets in New Mexico and Chihuahua. They transported over the Santa Fe and Chihuahua Trails a "bewildering variety of merchandise," said Moorhead. In addition to a broad array of cloths, "there were also the following items: clothing of all kinds; rings, necklaces, bracelets, earrings, crucifixes, beads, buttons, buckles, hairpins, ribbons, and handkerchieves [sic]; brushes, combs, razors, razor strops, mirrors, and cologne; clocks and watches; thread, needles, thimbles, scissors and knitting pins; curtain hooks, wallpaper, window glass, and white lead; pots, pans, coffee mills, dishes, corks, and bottles; wrapping paper, writing paper, pen points, pencils, slates, and books; candlewick, matches, percussion caps, gunflints, gunpowder, rifles, and traps; knives, axes, shovels, hoes and other tools; claret, sherry, and champagne." In the early days, the U. S. traders used mule trains, with anywhere from 50 to 200 mules, for transportation. They loaded each mule with some 400 pounds of cargo. They traveled 12 to 15 miles in an average day. In the later days, many traders turned to well-armed caravans of a few dozen Conestoga, or covered, wagons, each with a capacity of about two and one quarter tons, to transport their cargoes. The traders used teams of mules or oxen as draft animals, and they often argued over evening campfires about whether mules or oxen served the wagons best. Drivers of mule teams rode the draft animal on the left immediately ahead of the wagon. As in Spanish caravans, herders drove alternate teams and spare animals with the column. Often, the traders sold, not only their goods, but their wagons and some draft animals as well at the Chihuahua end of the trail. They returned up the Chihuahua Trail and back to Missouri only with mounts for the traders and pack animals for silver pesos.

Extraordinary Passages

In the wake of the Puebloan revolt of 1680, the more than 2000 Spanish refugees and several hundred Puebloan sympathizers – a total in the range of 3000 – funneled southward to the Fra Cristobal paraje, the campsite which became a gathering point at the northern end of the Jornada del Muerto. Ragged, hungry, exhausted, wounded and humiliated, the dispirited Spaniards trekked with their Puebloan allies in the late summer heat across the desert down the Chihuahua Trail to The Pass and, finally, refuge. En route, hundreds of the Spaniards disappeared from the column, according to Paul Horgan in his book Great River: The Rio Grande in North American History. He believed that many filtered back into Mexico and their original home communities. Other authorities have suggested that many died on the trail. Once they arrived at The Pass, the Spanish joined the budding community near the Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe mission church south of the river ford. Spanish authorities settled the Puebloans in new communities, with mission churches, downstream.

In the winter of 1841/1842, more than 180 of the captives from the failed Texas Santa Fe Expedition trekked southward in a forced march over the Chihuahua Trail en route to prison, escorted to The Pass by a sadistic commander, Captain Damasio Salezar, and 200 soldiers. The Passage across the Jornada del Muerto leg became a punishing test of human endurance for ragged, starving and wounded Texans. In his Narrative of the Texas Santa Fe Expedition, George W. Kendall, one of the prisoners, said that after a "long and tiresome march," the column arrived at the Fra Cristobal paraje, where it made camp for the night. At midnight, there "…commenced a violent fall of snow." When the sun rose, Kendall said that the snow had fallen to a "depth of five or six inches. My companions were lying thick around me, their heads and all concealed, and more resembled logs imbedded in snow than anything else to which I can compare them." Salezar then marched the column nonstop for the entire 90-mile length of the Jornada del Muerto. By the dawn of the second day on the trail, the prisoners "would sink by the roadside and beg to be left behind, to sleep and to perish." A prisoner named Golpin fell behind, and by the order of Salezar, a soldier shot the man "for no other reason than he was too sick and weak to keep up." The next night, the Mexican soldiers began torching yucca plants to snatch a moment’s heat. The Texans "crowded around them and as one would burn down to a level with the ground we rushed hurriedly to the next." Crossing the Jornada del Muerto, the Texans picked up a few Spanish words, usually oaths, from the Mexican soldiers. "It is singular," said Kendall, "how much more easily men learn to swear and blaspheme in any language than to pray in it."

In late 1846, when Colonel Doniphan marched down the trail to do battle with the enemy at El Brazito and the Sacramento River during the war with Mexico, he crossed the Jornada del Muerto with nearly 1000 troops, according to Robert Selph Henry in The Story of the Mexican War. En route, Doniphan’s force escorted U. S. merchants with more than 300 wagons loaded with commodities. "In all the ninety miles there was but one small waterhole," said Henry. "To lack of water, there was added suffering from cold, for it was now mid-December, the Rio Grande was running with ice, the bare elevated plain across which the road ran was swept by piercing winds, and even if there had been time for the usual halts around the grateful warmth of campfires, there was no wood with which to make them." Frank S. Edwards, a volunteer in the U. S. force, wrote in his chronicle, A Campaign in New Mexico with Colonel Doniphan, that, "Some of our men, thinking to avoid the usual suffering for water on this trip, got rather tipsy just before entering the jornada, calculating that, with a canteen full of whisky, they could keep in that state all the way across. Some did do, but others having used their canteens too freely, exhausted their stock the first night, and suffered terribly from thirst."

A decade and a half later, as Confederate general Sibley’s defeated force straggled in retreat to Mesilla, the Rebels sent a raiding party up the Jornada del Muerto, hoping to capture desperately needed horses from the Union forces at Fort Craig. Riding northward, the soldiers "happened upon a pond. Although their horses refused to drink, many thirsty soldiers, glad for the relief, dismounted and drank heavily. The pond was, however, heavily alkaline, or ‘poison,’ and scores of the men…became incapacitated with severe stomach cramps, vomiting, and ‘purging.’" The raiding party failed in its mission.

Travelers’ Scrapbook

From the first expedition of Spanish colonists to the coming of the railroad, travelers on the Chihuahua Trail, from Chihuahua City to Santa Fe, frequently suffered and sometimes died under the hardships of a march across the desert to the Southern Rocky Mountains. They also thrilled to the mystery and beauty and awfulness of an arid basin and range country haunted by those fearsome nomadic raiders, the Apaches and the Navajos.

Chihuahua City – "The first appearance of the town from a neighbouring hill is extremely picturesque, its white houses, church spires, and the surrounding gardens affording a pleasing contract to the barren plain which surrounds it… In this remote and but semicivilised city, I was surprised to find that they had surrounding themselves with all the comforts, and many of the luxuries, of an English home…"

From G. F. Ruxton’s chronicles of an 1846 journey

across Mexico, collected and published in Ruxton of the Rockies.

Sacramento River, Site of 1847 Mexican War Battle – "…the skeletons of our Enemies were strewed over the ground, having been dragged out of their graves by the wolves, great numbers of which we saw even in the day time. They had eaten all the flesh off… There are still many marks of the conflict, but everything thing of the least value has been carried away."

From George Rutledge Gibson’s journal

Over the Chihuahua and Fe Trails, 1847-1848.

Live Oak Lake – "This lake is ten or twelve mile long by two or three in width and seems to have no outlet even during the greatest freshets… The water…is so strongly impregnated with nauseous and bitter salts as to render it wholly unpalatable to man and best."

From Josiah Gregg’s 1830’s chronicle,

The Commerce of the Prairies.

Duck Lake – "…we arrived at the remarkable Lago de los Patos, Lake of the Ducks, which is about four miles in length, into which several large streams empty, but having no visible outlet. Its water, at most times, is too brackish for use; but now it was fuller than usual from there having been considerable rain in the mountains. This lessened the brackishness; and we found the water very welcome, for our poor animals had been entirely without any for three days and nights…"

From Frank S. Edwards 1847 chronicle,

A Campaign in New Mexico with Colonel Doniphan.

Samalayuca Sands – "These sand mountains were plainly visible from our camp, their yellow tops entirely destitute of vegetation of any kind, and presenting an appearance of dreary sterility."

From George Wilkins Kendall’s 1841 chronicle,

Texan Santa Fe Expedition

Samalayuca Sands – "…we reached Los Medanos [the sand dunes], a stupendous ledge of sand-hills, across which the road passes for about six miles…. These Medanos consist of huge hillocks and ridges of pure sand, in many places without a vestige of vegetation. Through the lowest gaps between the hills, the road winds its way."

From Josiah Gregg’s 1830’s chronicle,

The Commerce of the Prairies.

Rio Grande – "Joyfully [after crossing the Samalayuca Sands and reaching the Rio Grande], we tarried ‘neath the pleasant shade of the wide spreading trees which grew along the river banks. It seemed to us that these were, indeed, the Elysian field of happiness…"

From Gaspar Perez de Villagra’s History of New Mexico, a

chronicle of Juan de Onate’s 1598 colonizing expedition.

Rio Grande – The banks of the Rio Grande "are now nearly bare throughout the whole range of the settlements, and the inhabitants are forced to resort to the distant mountains for most of the fuel. But nowhere, even beyond the settlements, are there to be such dense cottonwood bottoms of those of the Mississippi Valley.

From Josiah Gregg’s 1830’s chronicle,

The Commerce of the Prairies.

The Pass – The river was "so thickly interspersed with vineyards, orchards, and cornfields as to present more the appearance of a series of plantations than of a town: in fact, only a small portion at the head of the valley where the plaza publica and parochial church [today’s Plaza de Armas and mission Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe of Juarez]."

From Josiah Gregg’s 1830’s chronicle,

The Commerce of the Prairies.

The Organ Mountains – "Los Organos [the Spanish name for the mountain range]" consisted "of an immense cliff of basaltic pillars which bear some resemblance to the pipes of an organ, whence the mountain derived its name." The Organ Mountains were one of two ranges in the region "famous as being the strongholds of the much-dreaded Apaches."

From Josiah Gregg’s 1830’s chronicle,

The Commerce of the Prairies.

Fort Selden – "The little outpost at Fort Selden became our home for the next three years. Company "K," with its two officers, its assistant surgeon, and forty-six enlisted men comprised the lonely garrison, sheltered in single-story, flat-roofed adobe buildings. It was here I learned to ride and shoot even before I could read or write—indeed, almost before I could walk and talk."

From Reminiscences: General of the Army Douglas MacArthur.

The Jornada del Muerto – "The country is quite level immediately around us, with dark hills in the distance. The grass is short and dry, the soil sandy, the little Prairie dogs have spread their habitation far and wide around and the whole puts on a gloomy aspect."

From 18-year-old Susan Shelby Magoffin’s diary of 1846-1847,

Down the Santa Fe Trail and Into Mexico.

The Southernmost Pueblos – "…being well within sight of the towns, it seemed the earth did tremble there, feeling the great force of the Church shaking the idols furiously, with horrible, impetuous violence and furious tempest and earthquake. All trembling and altered, it thus was troubled with fearsome shadow covering all the heaven with intricate clouds, and so dense, black, and fearful they caused us an awesome amazement…"

From Gaspar Perez de Villagra’s History of New Mexico, a

chronicle of Juan de Onate’s 1598 colonizing expedition.

Pueblos Along the Trail – "We visited a good many of these pueblos. They are all well built with straight, well-squared walls. Their towns have no defined streets. Their houses are three, five, six and even seven stories high, with many windows and terraces.

From Gaspar Perez de Villagra’s History of New Mexico, a

chronicle of Juan de Onate’s 1598 colonizing expedition.

Inside One of the Pueblos – "On the walls of the rooms where we were quartered were many paintings of the demons they worship as gods. Fierce and terrible were their features. It was easy to understand the meaning of these, for the god of water was near the water, the god of the mountains was near the mountains…"

From Gaspar Perez de Villagra’s History of New Mexico, a

chronicle of Juan de Onate’s 1598 colonizing expedition.

Santo Domingo Pueblo – "It has a very pretty appearance… The inhabitants were dressed in their gayest trappings; all mounted and armed. They dashed down towards us a full speed, and only when almost touching us, wheeled to right and left along our front, all the while discharging their few guns and pistols; and after separating into two parties, and going through a mimic battle, they formed around our officers, and escorted them into the Place. These were the largest and finest Indians I saw, and were dressed in showy costume."

From Frank S. Edwards 1847 chronicle,

A Campaign in New Mexico with Colonel Doniphan.

Santa Fe – "The town is very irregularly laid out, and most of the streets are little better than common highways… The only attempt at anything like architectural compactness and precision consists in four tiers of buildings whose fronts are shaded with a fringe of portales [entrances] or corredores [corridors] of the rudest possible description. They stand around the public square…"

From Josiah Gregg’s 1830’s chronicle,

The Commerce of the Prairies.

Santa Fe – "The plazo [plaza] or square is very large—on one side is the government house with a wide portal in front, opposite is a large church…’tis not finished – and dwelling houses – the two remaining sides are fronted by stores and dwellings, all with portals, a shed the width of our pavements; it makes a fine walk…"

From 18-year-old Susan Shelby Magoffin’s diary of 1846-1847,

Down the Santa Fe Trail and Into Mexico.

Santa Fe – The church is situated at the Western end, and though I cannot answer for the grandure [sic] of the inner side – to say nothing of the ‘outer walls’ – I can vouch for its being well supplied with bells, which are chiming, it seems to me, ‘all the time’ both night and day."

From 18-year-old Susan Shelby Magoffin’s diary of 1846-1847,

Down the Santa Fe Trail and Into Mexico.

Next month, in "Traveling The Chihuahua Trail," we will begin at the cathedral and plaza of Chihuahua City and follow the corridor across the northern Chihuahuan Desert to the Southern Rocky Mountains and end at the plaza in Santa Fe, stopping along the way to visit some of the most famous sites.

More Trails

Desert Trails

Trails of the Native Americans

Coronado Expedition from Compostela to Cibola

Coronado Expedition from Cibola to Quivira then Home

Chihuahua Trail 2

The Juan Bautista De Anza Trail

Jornada del Muerto Trail

Santa Fe Trail

The Long Walk Trail of the Navajos

The Desert Route to California

Bradshaw's Desert Trail to Gold

A Soldier's View of the Trails Part 1

A Soldier's View of the Trails Part 2

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms