Outlaw Endurance Trail Horse Ride

5 Days - 265 Miles

Text and photos By Wynne Brown

Several years ago, my husband and I hauled our horse, Salazar, to Utah so I could participate in the Outlaw Historical Endurance Ride. The five-day, two hundred-sixty-five mile ride began at Teasdale, a small community in the south-central part of Utah. The trail led southwest through the Aquarius Plateau, the Escalante River canyon, Little Desert, and the Escalante-Grand Staircase Monument.

Several years ago, my husband and I hauled our horse, Salazar, to Utah so I could participate in the Outlaw Historical Endurance Ride. The five-day, two hundred-sixty-five mile ride began at Teasdale, a small community in the south-central part of Utah. The trail led southwest through the Aquarius Plateau, the Escalante River canyon, Little Desert, and the Escalante-Grand Staircase Monument.

An endurance ride is very different from most riding experiences. The brochure advertising the event said that the trail would offer an experience that is "way beyond the comfort zone." For many of the riders who come from around the world, the primary goal is to be an "Outlaw," a rider who completes all five days on the same horse.

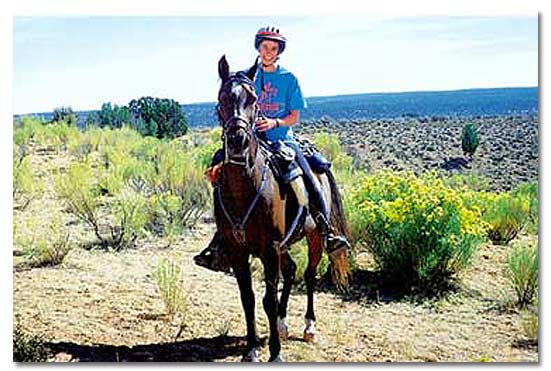

My goal was to ride as much of the trail as possible, one day or five, without overstressing Salazar. He was fifteen years old and a particularly easygoing Arabian with eleven years of endurance riding experience. He traveled well by trailer. He unloaded willingly every four to five hours all the way across the country, from the Southeast all the way to Utah, and spent nights in a portable corral we attached to our trailer. The front of the trailer has living quarters for Hedley and me.

The last fifty-mile stretch to Teasdale winds across the great red spine of the Escalante mountains, up and down deep scarlet clefts. That September, patches of aspen were just turning gold when we reached nine thousand five hundred feet elevation. It was glorious, and a valuable sneak preview of this rugged high country through which I was about to ride.

Endurance riding is partly about overcoming fear. Fear of falling off a cliff. Fear of getting lost for hours – or maybe days. Fear of skulking home and having to say, "I couldn't do it." I hoped that Salazar and I were ready for this.

Arrival

At noon, we pulled onto a windy hilltop in Teasdale and saw a banner announcing the "Outlaw Historical Endurance Ride." We immediately ran into the only other Southeastern riders, Jim Barnett and his son, Duane. Twelve states were represented. Top international riders were there from Brazil, Hungary, Germany, France and Canada.

Many endurance riders take a crew to help them at veterinarian ("vet") checks. I like riding "solo," which pleases Hedley, my husband. He did not want to ride. He insists that he is Not a Horse Person. (He is, however, a long-distance bike rider and an ex-marathon runner.) At the Outlaw Ride, Hedley's role was to get our rig to the new campsite each day.

I got checked and "vetted" in and scrambled around preparing for a six a.m. pre-dawn departure. There was a dusting of new snow on the mountain behind our camp.

At the ride briefing that evening, Crockett Dumas talked about the area's history and the local outlaws (including Butch Cassidy). Dumas and his wife, Sharon, are from Vadito, New Mexico, and they had been directing the Outlaw Historical Endurance Ride since 1977. They advertise it as the "Ultimate Endurance Adventure."

Sharon reviewed the trail, reminding us that there would be no access for emergency vehicles. The veterinarians warned riders with horses accustomed to low altitudes to monitor their animals carefully.

We would leave at six a.m., following Crockett at a controlled trot. Once it was light enough to see the trail markings (usually chalk marks on rocks or branches), riders could go at their own pace.

The group broke up, and camp quieted down soon after dark.

Day 1

Five a.m. came quickly, and we headed out single-file an hour later. I spent the day riding with Marilyn Bickley from Park City, Utah.

From the pinon-juniper habitat, we climbed steadily until we were in aspens, leaves scattered underfoot like gold coins. We could see deep blue lakes far below us. The "Rim Trail" is well-named. We were on a shelf, safe enough, but the trees below were such small specks that my stomach lurched a little every time I looked down. We soon ran out of "big" words. "Magnificent" and "vast" seemed flat.

The trail got steeper, and I got off to "tail," unhooking one rein and hanging onto Salazar's tail as he marched over the rocks so fast I almost had to jog to keep up. I had no feeling of altitude sickness, but I was out of breath. The trail became skinnier and steeper, and there was snow under trees and in rock crevices.

The last pull to Boulder Top was a mile-long slope of jumbled rock. Salazar took it at an even pace, always on-trail, with me hanging on for all I was worth.

The top was a series of flat meadows, some four or five miles long and two miles wide, all edged with spiky-looking dark firs. The wind whistled around my helmet. I was grateful for Polartec.

In late afternoon, Hedley met us, having run ten miles. The trail dropped off the mountain down a rocky escarpment, and Salazar had to pick his way through jagged boulders, being careful not to jam a hoof. I needed both hands for balance. In an act of ultimate trust, I tossed the rein over the saddle, and we worked our way down the mountain with him in front picking his way and me trailing several yards behind him.

Back in the aspens, the trail became a mud slide. Salazar tucked his hindquarters and calmly skied down. I tried the same thing and ended up on my butt.

The vet check finally appeared on top of another cold windy hill. Salazar dove into the hay, apples, carrots and bran, provided by ride management. The vet checked our horses and said they looked great.

Ten miles to go. We climbed back on, cold, stiff and ready for camp. It was getting close to dark.

At last, the Chriss Lake camp was in sight, and the horses perked up. We crossed the day’s finish line twelve and one-half hours after starting. Salazar's back was sore, but he was fine to go out again the next day. Aside from a headache and being bone-tired, the rider half of the team seemed all right.

By ten p.m., Hedley, Salazar and I were all asleep.

Day 2

It was frigid and pitch-dark at five a.m., but I was surprisingly limber and ready to ride.

We covered six to eight miles of mostly flat terrain with ankle-deep red sand. Everyone chatted and groused good naturedly about yesterday's trail.

The trail became several miles of the dreaded "slick rock," which was not slick at all. It was creamy-yellow sheets and rolls of sandstone with the texture of sand paper. It looked scary, but the horses' hooves had traction enough to trot or even canter.

More miles of sand and juniper and we arrived at the vet check in the community of Boulder, at a motel parking lot. Hedley said tourists had been intrigued all morning ("An endurance what??").

The vet checked Salazar's back: "Looks real good." Relief!

Jim Barnett and I headed out to cross twenty more miles of slick rock, an incredible area, an almost alien landscape with yellow-white gullies and towers stretching to a backdrop of red-orange mountains that fade to blue. We slithered down into canyons and clambered back out for more miles of the same, alternately riding, tailing, leading.

There was little vegetation, so the trail was marked with piles of rocks, or cairns. The sun beat down off the cliff faces, and it was warm in a T-shirt. All I could hear was the wind, which never stopped, and the grating of Salazar's shoes on the soft rock.

Fear?

No. I was deeply, purely happy, and my face hurt from smiling.

After three or four hours, we slid down a rutted crevice into the Escalante River canyon.

Dark red cliffs now towered above us. Flash floods had come through last week, wiping out the trail through the thickets of Russian olive, trees armed with inch-long thorns. Wading down the riverbed seemed easiest, if circuitous, but that route lost its appeal quickly when Jim's horse sank to the belly in quicksand. They floundered out, unhurt, but we eyed the water route suspiciously after that.

After an hour or two, we caught up with other riders, some bleeding, one missing his glasses, all of us wondering, "How much more?"

My smile was gone.

More hours and the canyon walls faded to grayish-brown. The river bottom widened into a road. Jim was burnt bright red. My lips felt permanently chapped. We drained my fourth water bottle. The horses seemed to know that we were almost done for the day. They trotted strongly through the small town of Escalante, now more alien to us than the slick rock.

The finish line for the day was on the race track of Escalante Desert Downs, and Hedley had camp all set up. The vets said Salazar "is a little stiff in front, his back is better than yesterday, and otherwise he's fine." I was so thrilled I forgot that I was tired.

We ate our spaghetti dinner in the grandstand with Marilyn, who had spent the day recovering from a cold, and her friend Moone Willetts, whose mementos from the river included a gashed nose, two blackening eyes, and a bruised chin.

We laughed, swapped tales, drank and ate some more. The moon, one day from full, rose over the valley in the half-light of dusk.

What a day.

What a horse!

Day 3

Today started with a silent four-mile ride through the Little Desert, honoring endurance riders and horses who have died. "Ghost Riders in the Sky" played softly as we left the racetrack. Sparks jumped as the horses' shoes struck the pavement.

We headed up a stony ridge until the early lights of Escalante were below us. The eastern sky began to gleam, Venus shining like a spotlight. All was silent except for the swish of hooves through sand, the occasional clink of a metal shoe against rock. Salazar trotted strongly.

The sun appeared, and we tried to get our antsy horses to stand still for a Kodak moment, and another picture was filled with equine ear tips.

The group spread out, and we climbed back up into the aspens and open slopes. Chalk guide marks had been obliterated by last week's rain, and Duane Barnett and I took a couple of wrong turns. Then we realized his mare had gone lame. He urged me to go on without him, but we stayed together to Griffin Top, another eleven thousand two hundred foot high plateau where the markings were few and far between. The wind ripped. It was sleeting by the time we reached the vet check.

Salazar got the O.K. to go, and Judy Saunders and Ron Savard, from Ontario, and Janin Cameron from California welcomed another pair of eyes to help hunt for markers.

Twenty miles to go.

As the afternoon wore on, I had a sneaking feeling that Salazar was not quite sound. We alternated between riding, tailing and leading as the trail roller coastered along the spines of six long red ridges dotted with white rock outcrops and bristlecone pines. In the distance were miles of more red rock country.

Finally, we saw the Canadian crew. "Only three miles to go!" they told us.

We trotted across a flat sandy trail that wound through the rabbitbush, and within several yards I knew definitely that something was wrong. Salazar was eager but striding short. I made him walk (marveling that he wanted to trot after one hundred sixty five miles), worrying, but also relishing the solitude, the silence, the evening light.

About a mile from camp, Hedley met us. We had finished the day’s ride in a time of eleven hours. Once in camp, I realized Salazar had "scratches," a form of dermatitis, above his hoofs. Although the vet said we could go out the next day, I smeared Desitin on his lower legs and decided to take a day off. Salazar had done three hard travel days, followed by three hard riding days back-to-back.

Besides, I really wanted to hike Bryce Canyon with Hedley.

Day 4

We camped at Widstoe, a ghost town settled by Mormons who were "droughted out." At five a.m., there was ice on the water buckets.

The riders milled around, illuminated by lanterns and the occasional headlights, then left in a cloud of dust. Hedley and I retreated to the warm camper and a real breakfast. We packed up, drove to the next night's campsite, and got Salazar settled in.

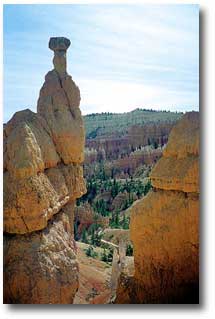

Bryce Canyon is only thirty minutes – and a world – away. After the solitude and athleticism of the last three days, busloads of overweight tourists made us feel like some weird alien species. But the canyon itself was magnificent.

Hedley and I walked down into the canyon, past layer upon layer of spires, towers and "hoodoos" that almost glowed in the early afternoon light, a hike well worth missing a day of riding. We headed back to camp where Salazar pawed the ground impatiently. I could see that he was ready to go out again. The vet agreed.

After dinner, we all stood around a welcome fire, laughing, chatting and taking in the lunar eclipse.

Day 5

Today would be an easy day, so we did not leave until a leisurely seven a.m.. The moon sank in front of us as the sun rose behind us. Many horses get stronger on a multi-day ride, and Salazar was no exception.

Once we reached the Pahrea River Canyon, I lingered, wanting this final day to last. We crossed and re-crossed the ankle-deep river, fortunately free of quicksand.

The Barnetts caught up, and we rode together slowly for several miles, enjoying the day. Salazar felt too good to walk, so we trotted on ahead. The canyon widened out, the cliffs turned from tan to pink, then shrank to hills. We crossed the river one last time, to the vet check. As I trotted him out, the vet commented, "Who's leading whom?"

Twelve and a half miles to go.

We came to the old Pahrea Movie Set where "The Outlaw Josey Wales" was filmed. A handful of tourists looked disappointed that I was not wearing chaps and a cowboy hat. I tipped my helmet and trotted on through.

Salazar asked to canter. I was so proud of both of us that it brought tears.

Seven or eight miles later, a lone form appeared. Who else but Hedley would be out here in the desert on foot? Salazar nickers and, after a celebratory picture (Kodak should sponsor this ride), the three of us trotted on, Hedley in the lead.

We passed the two French riders and then a Brazilian, and then, after two hundred and ten miles in five days, Salazar broke into a canter and we crossed the finish line, accompanied by cheers from the waiting crowd. I was in tears again.

Back Home

Eight weeks later and the spell of the Outlaw Trail was still with me. Visualizing those sandstone cliffs, still hearing the wind whistle at Griffin Top, feeling Salazar asking to canter that last mile – all those memories helped put the tribulations, and yes, the fears, of "Real Life" into perspective. Many events fail to live up to their billing, but the Outlaw Ride, for me, was truly the "Ultimate Endurance Adventure."

What to Bring

Packing

How do you pack for a twelve-hour day on a horse in the wilderness, a day that can be in the 80’s or maybe bring snow?

Carefully. And with the worst-case scenario in mind.

Water: I packed four water bottles, two on the saddle and two in the wither bags that hang on either side of the horse's shoulders.

Horse food and supplies: In the left wither bag were grain, carrots, electrolytes and a hoof pick.

Rider food and supplies: In the right bag were gorp (homemade trail mix with raisins, M&M’s, peanuts), sesame sticks, homemade beef jerky, camera (disposable ones are great), a Powerbar and Advil.

Essentials: In a mini-waist pack were personal hygiene items, knife, map, lip balm/sunscreen, emergency space blanket, waterproof matches, a Powerbar and a mini-flashlight. This pack held what I would need if Salazar and I got separated (grim thought), but it was soft enough that I would not break a rib if I fell on it.

Extra clothes for both: I added a "rump rug" to the saddle. It could be unrolled to keep Salazar's hindquarters from cramping in the cold. I carried a Goretex jacket for me. I also tied on a sponge to cool Salazar off in creeks in case he got overheated.

Rider clothes: Polartec fleece tights and layers (T-shirt, flannel shirt, Polartec jacket), gloves and helmet. Hiking boots worked well, since I walked a lot to help the horse.

Horse tack: Most important, a saddle that fits. Salazar "wore" his usual custom-made DeSoto endurance model that looks like a cross between an English and a Western saddle. A breast collar helped keep it in place and gave more surface to tie things to. A hackamore bridle (a bridle without a bit) allowed him to eat and drink freely.

The Endurance Ride

An endurance ride is a race, although many contestants choose to ride the marked trail at their own pace. Distances range from twenty five, fifty, seventy five or one hundred miles in one day to a typical two hundred and fifty miles in five days. The maximum time limit for a day’s ride is six hours for a twenty five mile ride, twelve hours for a fifty mile ride and twenty four hours for a hundred mile ride.

Most endurance rides are sanctioned by the American Endurance Ride Conference, which requires strict veterinary supervision. Any breed of horse or mule is welcome, but the animal must be at least four years old to compete in a twenty five-mile ride and five or older to compete in distances of fifty miles or more.

The AERC sanctions approximately five hundred rides a year all over the United States. The sport is now international.

For more information, contact the:

American Endurance Ride Conference

1373 Lincoln Way, Auburn, CA 95604

Mailing address:

AERC, P.O. Box 6027, Auburn, CA 95604

Phone: 866-271-2372 or 530-823-2260

Related DesertUSA Pages

Desert Horseback Riding & Equestrian Trails

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms