The Anasazi

Community Planners, Architects and Builders - Part 2

At their cultural zenith, during the first third of the second millennium, the Anasazi Pueblo people, possibly numbering several hundred thousand, emerged as the preeminent community planners, architects and builders among the desert cultures. Anasazi groups, widely scattered across the southern Colorado Plateau and the upper Rio Grande drainage, defined their similarities – and their differences – largely in terms of their multi-storied, multi-room pueblo "Great Houses" or "cliff dwellings" (even though most of the population lived as extended families on small scattered farmsteads).

Cultural Similarities and Differences

The Anasazi groups shared a cultural affiliation which probably impelled them to undertake the construction of large pueblos within the same general time period. Individual groups, however, likely saw themselves as cultural entities who lived in diverse environments, and that view affected their specific approaches to building the structures.

On one hand, the Anasazi groups bore similarities in that they descended from hunting and gathering and early village farming peoples who excelled in basketry. They began making pottery centuries later than their cultural affiliates in the northern Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts. Most of them moved from pit houses to walled surface structures during the same general time period. They began building multi-storied, multi-room pueblos, it seems, in answer to a common urge. Some constructed large kivas, or ceremonial chambers, for community activities and ritual, and all built small kivas for family activities and ritual. They raised corn, beans and squash, depending on either rain or irrigation for nourishment of their crops, and they supplemented their harvests in the old traditional way, by hunting and gathering.

They anticipated the coming and going of the seasons by tracking the passage of the planets and the stars. They focused their ceremonies on the broad concepts of harmony and balance in life and nature, and they believed that their ceremonies, properly done, would be ratified by sufficient rain, abundant harvests, successful hunts and good health. They held beliefs with common threads about their origins and deities. They used similar cultural icons as ritualistic symbols, which seem to have sprung from common cultural wellheads. For instance, their step-sided rain cloud altars and their goggle-eyed and snarling-mouthed ceremonial masks probably had roots in the great civilizations of southern Mexico. Their horned masks and their rock art deer and big-horn sheep images likely had origins in long hunting and gathering traditions. Their Kokopelli – or hump-backed flute player – figures could ultimately prove traceable to Peru, and may have been symbolic of fertility, prosperity and celebration.

in life and nature, and they believed that their ceremonies, properly done, would be ratified by sufficient rain, abundant harvests, successful hunts and good health. They held beliefs with common threads about their origins and deities. They used similar cultural icons as ritualistic symbols, which seem to have sprung from common cultural wellheads. For instance, their step-sided rain cloud altars and their goggle-eyed and snarling-mouthed ceremonial masks probably had roots in the great civilizations of southern Mexico. Their horned masks and their rock art deer and big-horn sheep images likely had origins in long hunting and gathering traditions. Their Kokopelli – or hump-backed flute player – figures could ultimately prove traceable to Peru, and may have been symbolic of fertility, prosperity and celebration.

On the other hand, the Anasazi groups differed in significant ways. For instance, groups developed different political structures, ceremonies, rituals, burial practices and ceramic designs. They probably spoke several different languages, much as we see in today’s Anasazi descendants. For instance, today’s Hopi, in northeastern Arizona, speak a Uto-Aztecan dialect. The Zuni, in west central New Mexico, speak a unique language, what linguists called a "language isolate;" with no known roots. Other western pueblos, for instance, Acoma and Laguna, speak dialects of the Keresan language. The eastern Pueblos speak dialects of the Tanoan language. Perhaps most notably, the prehistoric Anasazi groups developed different approaches for coping with different environmental settings with different resources. For instance, some developed strategies for living in arid shallow canyons with abundant building stone, limited construction timbers, substantial arable land and reasonably long growing seasons. Others developed strategies for living in deeply cut canyons with adequate building stone, abundant construction timbers, limited arable land and shorter growing seasons.

The groups expressed their cultural similarities in their drive to build large pueblos, but they translated their local cultural and environmental differences into variations in the planning, architecture and construction of their communities.

The Spiritual Center

When their Creator, sometimes called "The Grandmother," summoned the Anasazi people from the underworld through a portal, or sipapu, onto earth’s surface, she directed them to find the "Center, or Middle, Place" to build their pueblos. She spoke of both a geographical and a spiritual core, a location which promised harmony and balance. She imbued them with a high regard for the resources of the earth, a recognition of the importance of direction and village orientation, a deep awareness of the march of the seasons, a veneration for spirituality and sacred places, and a reverence for their origins.

Responding to the guidance of their creator, the Anasazi chose village sites which, ideally, lay near a water source, tillable and irrigable fields, abundant game, useful wild plants, firewood, stone quarries and construction timbers—a Center Place which promised harmony and balance between their needs and the natural world. They often positioned structures, not only to mark their place at the "center," but also to serve as instruments for tracking the celestial movements and predicting seasonal change. They used sacred places, often a mountain or prominent butte, for spiritual quests and shamanistic ritual but not for living sites.

They excavated small depressions in the center of their ceremonial chambers and sometimes their lodges to remind them of the sipapu. They knew that miscarried ceremony, failed shamanistic ritual, untimely seasonal change, drought or misspent resources could yield a breakdown in the harmony and balance of their community. They knew that discord could bring hardship for the people, clashes among families or clans, abandonment of a pueblo, migration to an unknown new location, and, ultimately, a renewed search for the Center Place. The Anasazi migrated frequently.

At their pinnacle, however, the Anasazi – those within the cultural spheres defined by the populations of Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde and the southwestern Colorado Plateau – built the most imposing pueblo communities ever seen in the southwestern United States or northern Mexico.

Chaco Canyon Great Houses

Early in the second millennium, Chaco Canyon, the first "Rome" of the Puebloan world, served as the political, religious and cultural center of gravity for a network of communities loosely knitted together by roads or road segments, all converging on the core. The territory "included nearly 40,000 square miles, an area larger than Scotland," Dave E. Stuart said in Glimpses of the Ancient Southwest. The dozen Chaco Canyon Great Houses are "the principal ‘fact’ of Chaco," Stephen H. Lekson said in his book, The Chaco Meridian: Centers of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest. "They were architecture by any standard, designed by one (or a few) to be seen by many." Built for the elite, the Chaco Canyon Great Houses stood as the Puebloan equivalent to England’s Buckingham Palace, France’s Versailles or Spain’s Royal Palace.

Typically, the residents of Chaco Canyon, in northwestern New Mexico, built Great Houses which included room blocks with spaces for living quarters, storage, towers and family or clan kivas; a large plaza with areas for food preparation, work and ceremony; and a community kiva, or "Great Kiva," with features for community activities and ceremonies. They sited most of the Great Houses on the north side of the canyon, facing south, although they built several up on the mesa.

For example, the almost perfectly D-shaped Pueblo Bonito, apparently the largest, perhaps the most architecturally elegant, and certainly the most celebrated of the Chaco Canyon Great Houses, stood five stories in height along its back perimeter rooms. Located in the canyon on the north side, it faces south and encompasses a large plaza. At its peak, it had some 700 (some suggest as many as 800) rooms, 37 family kivas, and two community kivas, or Great Kivas. Built in several stages, it covered more than four and one half acres. Over time, workers shaped an estimated one million blocks of sandstone weighing a total of some 30,000 tons to construct the walls of Pueblo Bonito, and according to a study by University of Arizona researchers, the workers hauled spruce and fir timbers more than 50 miles, from the Chuska Mountains to the west and the San Mateo Mountains to the south, to construct floors and roofs. (The researchers estimated that, altogether, the laborers transported – on their backs! – more than 200,000 timbers from the mountains to Chaco Canyon for construction of the Great Houses.)

The principal community planners of the Chaco Canyon Great Houses aligned the structures with cardinal directions or with celestial events. The principal axes of Pueblo Bonito, for example, point almost exactly in the cardinal directions. More astonishing, according to researchers from the University of Colorado, axes of other Great Houses appear to be aligned with "lunar standstills," the point when the moon makes its northernmost ascension over the earth’s horizon—an event which only occurs every 18.61 years.

According to Lekson in his study Great Pueblo Architecture of Chaco Canyon, the Chaco Canyon planners faced Great Houses within the canyon to the south so they could capitalize on solar warmth during the winter. (I have seen Chaco Canyon blanketed with a heavy snow in the middle of the winter. You would want all the solar warmth you could get.) If practicable, they used natural barriers to protect residents from the prevailing winds. For instance, they used the north canyon wall to shield Great Houses from the north winds of winter. They incorporated natural features into some of the structures. They provided for views of neighboring Great Houses. They may have designed the Great Houses – like Juvara, Sachetti and Sabatini designed Spain’s Royal Palace – to impress the "masses."

Typically, during the planning and design stage, said Lekson, the architect – with a vision of the completed structure in his mind – laid out a Great House arrangement, not with some sort of rudimentary drawing board and drafting instruments, but with lines on the earth’s surface, perhaps marking corners with posts and tracing wall lines with cobbles. He made certain that building axes lined up with cardinal directions or celestial events. Before construction began, workers moved large volumes of soil to prepare and level a site. They then built foundations along all the architect’s wall outlines by excavating ditches about two feet wide and two feet deep and filling them with stone rubble and clay mortar. They could then begin construction of the walls.

Masons constructed Great House walls from sandstone and clay mortar. They quarried the sandstone from outcrops in the immediate vicinity or from exposures up to three miles away. They shaped the stones into building slabs by hammering, grinding or grooving and snapping them. They used wooden lintels over doors and windows. To insure stability and strength, the masons built thick walls for the first story and increasingly narrow walls for each succeeding story. They built some walls of a single stack of shaped stones, others of two adjoining stacks of shaped stones, still others of interlocking adjoining stacks of shaped stones, and still others of rubble cores with shaped stone interior and exterior facings. The craftsmen produced decorative veneers by wedging spalls into the mortar between slabs, alternating rows of small slab bands between rows of thicker slab bands, or carefully shaping and fitting individual slabs of varying thicknesses.

Chaco Canyon construction workers built their Great House floors and roofs by using the timbers from the Chuska and San Mateo Mountains as the primary beams, or "vigas." They laid smaller logs across the vigas to serve as secondary beams, or "latillas." They blanketed the latillas with split shakes, which they capped with a mortar of clay and, finally, a layer of sand. The workers spread sand to level the ground floors of apparent storage rooms, and they spread sand and plastered it with clay to accommodate the residents of apparent living rooms.

Within the room blocks, the builders constructed large rectangular and mystifying T-shaped doorways with timber lintels to permit passage from space to space and from the building to the plaza. For some inexplicable reason, they built doorways which connected adjoining corners of some rooms even though conventional doorways often connected the same rooms. They built small doorways, or crawl spaces, which residents seem to have used to reach the apparent storage rooms. The occupants probably used woven mats, blankets or hides to close the large doorways and flat stone slabs to cover the small openings.

The workers plastered exterior walls with clay mortar, masking their excellent stonework from view but protecting it from rain and wind. They plastered the interior walls of living quarters and kivas with a clay mortar, often rendered white by the inclusion of caliche, and sometimes artists painted murals or designs on the surfaces.

The Chaco Canyon designers and builders committed major investments in manpower to the construction of the most massive of single Great House structures, the architecturally central Great Kivas—circular semi-subterranean ceremonial chambers which, archaeologists believe, served as the social and spiritual centers of the Great Houses. William M. Ferguson and Arthur H. Rohn called the Great Kivas "the Anasazi counterpart of the Gothic cathedrals of Europe built at about the same time" in their book Anasazi Ruins of the Southwest in Color.

In building Chaco Canyon-style Great Kivas, which typically ranged from 40 to 70 feet in diameter and 12 to 16 feet in depth, workers excavated as much as 2000 cubic yards of earth. They lined the kivas with elaborate masonry walls, often building in niches or crypts. They used four 2- to 3-foot diameter support timbers, seating them on stacks of sandstone disks and encasing the bases in masonry collars. The disks measured three feet or more in diameter and six inches in thickness, and each one weighed some three quarters of a ton. The workers built benches, or banquettes, around the perimeter of the wall, topping the benches with intermittent load-bearing columns, or pilasters. Along the south-to-north axis, the builders constructed vents to induce a flow of air between the inside and the outside; a slab fire screen to deflect an otherwise uncomfortable air draft; a stone-lined pit to contain fires; a small floor cavity to symbolize the sipapu; and, just outside the kiva walls, an altar room presumably for use in preparations for ceremonies. On either side of the south-to-north axis, they built a sunken or a raised vault, serving an unknown purpose. They roofed the Great Kivas with logs, bark and soil, presumably leaving an hatch for access by ladder. Sometimes, they built auxiliary rooms immediately outside the perimeters of the Great Kivas.

In their book Chaco Canyon, Robert and Florence Lister describe Edgar L. Hewitt’s excavation of the Great Kiva of the Chaco Canyon Great House called Chetro Ketl during the 1930’s: "When this chamber was opened to its uppermost floor level, it revealed a typical Great Kiva with niches in the wall, encircling bench, seating bins for the roof supports, vaults, firebox or altar, and a plaza-level antechamber from which entrance to the kiva proper was gained by means of a series of steps… …ten carefully sealed foot-square niches, or crypts, were discovered around the wall above the bench. Upon opening them, it was found that every one contained a ritual offering, or a set of religious paraphernalia. Luckily, they had remained undisturbed from the day they had been left there by the ancients. Each cache had a great number of black and white stone and shell beads that originally had been strung as long necklaces or garlands, plus numerous pieces of both unworked and shaped turquoise. The ten necklaces are remarkable samples of Anasazi craftsmanship…"

"This is one of the classic finds in Southwestern archaeology," said authority John Kantner, Georgia State University, in his internet website, "one that every archaeologist working in the region wishes he or she could have experienced."

In their investigations of Chaco Canyon, researchers remain baffled by many aspects of the Great Houses. How did a presumably elite social stratum marshal the manpower resources necessary to build the massive structures? Why did they select the arid Chaco Canyon as the Center Place for their building sites? Did they recognize a social, political or religious hierarchy in the importance of the Great Houses? How did the Great Houses relate to each other? As competitors? As cooperative communities? Collectively, did they serve as a regional center of trade? A colonial outpost for southern Mexico’s great city states? A manufacturing center for trade goods such as turquoise jewelry and ornaments? A political, religious and ceremonial center for satellite pueblos? A redistribution center for balancing food surpluses and shortages within the region? Or some combination of functions?

The researchers are equally puzzled by a number of specific features associated with the Great Houses. At the Great House known as Pueblo Alto, for instance, they have discovered that the trash mound, or midden, contained a stunning 150,000 broken ceramic vessels; this is far more than would be expected from the resident population. At the Great House known as Pueblo del Arroyo, they have found a large masonry feature comprising three concentric circular walls, apparently built late in Chaco history by Anasazi people from the Mesa Verde region; the purpose of the tri-wall structure – the only one in Chaco Canyon – is not understood, although some call it a "tri-wall kiva." At several of the Great Houses, investigators have discovered cylindrical masonry towers – "tower kivas" – which rose for two or three stories above surrounding room blocks; the towers may have served, according to speculation, as ceremonial structures, communications towers, lookout towers, or rudimentary lunar and solar observatories. In investigations not only of the Chaco Canyon Great Houses, but of other pueblos across the Southwest and northern Mexico, archaeologists have long wondered about the T-shaped doorways; originally, some believed that the doorways spread northward from southern Mexico and served to facilitate entry by individuals with large burdens on their backs; now, others believe that the T-shaped doorway may have spread south into Mexico and have spoken, architecturally, as some kind of symbol.

In The Chaco Meridian: Centers of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest, Steve Lekson

discusses the puzzling and "remarkable thirteen-pillar colonnade" at Chaco Canyon’s Chetro Ketl. He says that "?the pillars are rectangular stone masonry and rise from a low base wall?" Other than the colonnades at the huge and much later Paquime ruin in northwestern Chihuahua, the one at Chetro Ketl is "unique in the greater Southwest." It may represent influences from Mesoamerica.

Lekson also mentions "room-wide platforms," which "were very deep shelves, built with primary and secondary beams much like roofs, midway between floor and ceiling in both ends of rectangular rooms or in room-sized alcove… Their purpose is obscure…"

The scholars have found the famed Chacoan roads, which include both main arteries and short segments, to be especially puzzling. In a paper which he presented to the conference "Evaluating Models of Chaco" in 1997, John Kantner said that the Chacoan main arteries – most notably, the North and South Roads – extend "from Chaco Canyon to outlying areas on the edges of the San Juan Basin." The segments seem "to emanate from a great house or great kiva and extend only a short distance."

The Chacoans built many of the roads, some up to 30 feet wide, in near-straight lines, leveling mounds and washes, constructing ramps and stairs, to negotiate obstacles such as hills and mesas. In some stretches, they bordered the roads with masonry walls, stones, earthen berms or grooves. In some locations along the route, they built crescent-shaped stone shrines, small stone structures, earthworks and rubble platforms. In a few instance, they built two and even four closely parallel roads which serve no obvious practical purpose.

Archaeologists have speculated that the roads served for avenues for trade, carriage or pilgrimages. In his essay "The Chacoan Roads" in the book Anasazi Architecture and American Design, Michael P. Marshall said, "The Anasazi roads are not an interconnected transportation network…" Rather, they may be "cosmological corridors that link ceremonial architecture to various topographic features, horizon markers, and directional-astronomical orientations. This cosmological function for the Chacoan roads is supported by the use of constructed roadways as sacred pilgrimage avenues by historic and modern Puebloan peoples. The construction of roads to [sacred] lakes and springs and the frequent north-south orientation of roads is a common feature of both historic Zuni-Acoma roads and the Chacoan roads." If Marshall’s premise is correct, the prodigious investment of labor required to construct the roads of Chaco give a measure of the spirituality of the Anasazi people.

For reasons which we may never fully understand, the Chacoans began to abandon their region early in the 12th century. At least some moved 50 miles due north, and they built new Great Houses at the site we now call "Aztec," on the banks of the Animal River. They would abandon that location, too, in the following century.

Mesa Verde

The Mesa Verde Anasazi people, who approached their cultural crest at about the time the Chacoan people began their decline, faced different circumstances in the planning, design and construction of their multi-storied, multi-room communities within the higher and colder ranges of southwestern Colorado and southeastern Utah. Compared with most of the Chacoan Anasazi, the Mesa Verdans lived in a more dissected country. They had to mold their multi-storied, multi-room pueblos, with the typical room blocks, plazas and kivas, into the landscape.

Those who built the famed cliff dwellings within the alcoves of the deep canyons in what is now Mesa Verde National Park conceived of their structures as an integral part of a monumental sculpture by nature, not as an edifice on the floor of a canyon. In his essay "Learning From Mesa Verde" in Anasazi Architecture and American Design, architect Anthony Anella said, "…the great palaces of sandstone are inconceivable without the protective alcoves of the surrounding rock. Here, architecture is given meaning by an order established by geology."

Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace ruin, said Anella, is particularly special because "…the plan of the building conforms to the pre-existing order of the cliff rather than to a preconceived order of human intervention. The dry-laid masonry walls run either parallel or perpendicular to the natural slope of the alcove floor. Further, the walls are laid just inside the drip line of the protective alcove overhead… The architecture of the Anasazi at Mesa Verde achieves a compelling balance between the human program and the geological circumstances and topographical idiosyncracies [sic] of the site. A tangible sense of place develops in the architecture because it is premised on a powerful sense of belonging to a larger natural whole." (I saw Cliff Palace for the first time in 1950, and even as a young boy, I could feel the powerful sense of unity between the structures and the canyon alcove.)

In her book, The Professor’s House, Willa Cather described her impression when she first saw a Mesa Verde cliff dwelling. "?set in a great cavern in the face of the cliff, I saw a little city of stone, asleep," she said. "It was as still as sculpture—and something like that. It all hung together, seemed to have a kind of composition: pale little houses of stone nestling close to one another, perched on top of each other, with flat roofs, narrow windows, straight walls."

Embraced by stone alcoves, the Mesa Verde cliff dwellers built smaller and more intimate living and storage room blocks than those of the Chaco Canyon Great Houses. In fact, the Mesa Verdans could scarcely stand erect beneath their low roofs. They built smaller doorways, making them easier to close against the winds of winter. They built integrated courtyard, kiva and storage complexes, suggesting that the structures served not only for community and religious functions but for barter and trade as well. Like the Chacoan people, the Mesa Verde cliff dwellers built benches, wall niches, vents, deflectors, fire pits, floor vaults and altar rooms into their kivas, but sometimes, they made the floor plan of the structures square or rectangular rather than circular. They punctuated their Great Houses with towers, with both square and circular floor plans, which rose above the surrounding room blocks. The one at the Square Tower House ruin stands some eight stories high. Unlike the Chacoans, who used sandstone slabs to build walls, the cliff dwellers used shaped sandstone blocks, which they plastered with clay. They painted the interior walls with murals of red and white abstracted designs and perhaps mountainous horizons.

During the same time period, at Hovenweep, in the arid sage, grass and canyon country of southeastern Utah, people of the Mesa Verde branch of the Anasazi also built pueblo complexes at the heads of shallow canyons fed by springs. Like the cliff dwellers, the Hovenweep groups built their room blocks and kivas of shaped sandstone blocks. Unlike the cliff dwellers or the Chacoans, however, the Hovenweep people did not built Great Kivas. Rather, they built what are apparently ceremonial towers, some of the most strange and distinctive in the region. With no apparent thought of observational purposes, they constructed some of the towers on large boulders, others on canyon rims, still others on canyon floors. Ferguson and Rohn speculated that the towers "most probably had ceremonial significance in Anasazi culture akin to totem poles for the Indians of the Northwest, obelisks for the Egyptians, or stone heads for the Olmecs and Easter Islanders." The towers of Hovenweep remain one of the enduring enigmas of the Pueblo Southwest.

The Mesa Verde Anasazi began abandoning their region late in the 13th century.

Kayenta

In the southwestern corner of the Colorado Plateau, primarily in northern Arizona, the branch called the Kayenta arrived late to the cultural cresting of the Anasazi. The Kayenta people, however, made their mark in some of the most majestic settings in the entire Southwest.

In the second half of the 13th century, for instance, they built the cliff dwellings known as Betatakin and Keet Seel in towering alcoves in Tsegi Canyon, in northeastern Arizona. Less skilled masons than either the Chacoans or the Mesa Verdans, they constructed room block and kiva walls from roughly shaped stones set in a mud matrix. They built other walls from posts plastered with mud—the same jacal-type construction their ancestors used to build the earliest Kayenta walled surface structures. They built fewer, simpler and smaller kivas, possibly including a few at some distance from the cliff dwelling. They built only one kiva, square in floor plan, at Betatakin and only four kivas, including one with some Chacoan and Mesa Verdan style features, at Keet Seel. The populations, never more than 100 to 150 for each cliff dwelling, abandoned their homes and the region around the turn of the century, in less than a lifetime after the major construction began.

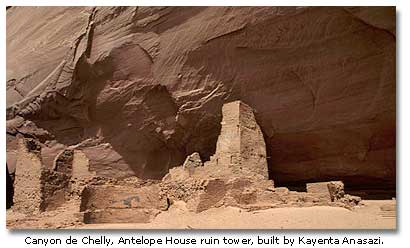

In the middle of the 12th century, the Kayenta Anasazi began building multi-storied, multi-room pueblos in the alcoves of the stately 1000-foot high sandstone walls of Canyon de Chelly and its branch Canyon del Muerto. (My wife and I spent two days exploring the canyons in the late 1980’s with a Navajo guide, Gary Henry, who made the trip one of the great experiences in the archaeology and history of the Southwest.) Like the builders of Betatakin and Keet Seel, the Canyons de Chelly and del Muerto residents built a few small kivas. They built perhaps one Great Kiva, a rectangular roofless structure near the ruin called Mummy Cave, and at a site isolated from the cliff dwellings, they built a ceremonial center, with three Great Kivas.

Ominously, the canyons foretell a time of great change in the Anasazi Southwest. In the stone walls of the ruins, archaeologist find not only masonry which is the trademark of the Kayenta. They see a classic tower of the Mesa Verde Anasazi at Mummy Cave and the refined masonry of the Chaco Anasazi at the ruin called White House. The stone walls of the cliff dwellings of the canyons speak of restlessness and movement across the lands of the Anasazi.

Abandonment

By the 14th century, the Anasazi had abandoned the Chacoan region, the Mesa Verde region and the southwestern Colorado Plateau, leaving behind what Willa Cather might have called "empty cities of stone, asleep, still as sculptures," splendid examples of prehistoric planning, architecture and construction. In a quest for a new Center Place, they migrated southward to the Little Colorado River and its tributaries and eastward to the upper Rio Grande and its tributaries. Calling on their old skills as planners, architects and builders, they founded new communities or expanded existing communities, sometimes making them even larger than the old communities, though not as architecturally elegant as Chaco Canyon’s Pueblo Bonito or Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace. Their descendants still occupy some of the later pueblos, for instance, the Hopi and Zuni villages, Acoma, Laguna, Taos, San Ildefonso and Isleta; and they eventually abandoned others, now in ruins, for example, Puye, Bandalier, Pecos, Kuaua, Gran Quivira, Quarai and Abo. In some areas, the migrations led the Anasazi to merge with their cultural kin, the Mogollon of southern New Mexico and northern Chihuahua and the Hohokam of south/central Arizona and northern Sonora, with a consequent blurring of cultural lines.

Archaeologists have no clear understanding of the monumental changes which swept across the Southwest in the first third of the second millennium. We will explore those mysteries in the next part of this series.

Anasazi Archeological Sites

- Anasazi Heritage Center, CO

- Aztec Ruins National Monument, NM

- Bandelier National Monument, NM

- Butler Wash Overlook, UT

- Black Mesa, AZ

- Canyon de Chelly National Monument, AZ

- Chaco Culture National Historic Park, NM

- Chimney Rock Archeological Site, CO

- Crow Canyon Arecheological Center, CO

- El Morro National Monument, NM

- Grand Canyon National Park. AZ

- Kinishba Ruins, AZ

- Lowry Ruins, CO

- Homolvi Ruins State Park, AZ

- Hovenweep National Monument, UT

- Mesa Verde National Park, CO

- Mule Canyon Ruins, UT

- Navajo National Monument, AZ

- Newspaper Rock Sate Historical Park, UT

- Pecos National Monument, NM

- Petrified Forest National Park, AZ

- Salinas National Monument, NM

- Salmon Ruin, NM

- Ute Mountain Tribal Park, CO

"Paleo-Indians" (Part 1)

Desert Archaic peoples( Part 2)

Desert Archaic peoples - Spritual Quest (Part 3)

Native Americans - The Formative Period (Part 4)

Voices from the South (Part 5)

The Mogollon Basin and Range Region (Part 6)

The Mogollon - Their Magic (Part7)

Hohokam the Farmers (Part 8)

The Hohokam Signature (Part 9 )

The Anasazi (Part 10)

The Anasazi 2 (Part 11) This Page

The Great Puebloan Abandonments (Part 12)

Paquime (Part 13)

When The Spanish Came (Part 14)

Life on the Margin (Part 15)

Life on the Margin (2) (Part 16)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 1 (Part 17)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 2 (Part 18)

The Outside Raiders (Part 19)

The Enduring Mysteries (Part 20)

Some Sites to Visit (Final Part)

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms