The Puebloan People

When The Spanish Came

By the time Cabeza de Vaca, Estevanico, Fray Marcos de Niza, Francisco Vazquez de Coronado, Juan de Onate and others wrote their names into the history of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico in the 16th century, the Puebloan peoples had abandoned more than 50 percent of their ancestral homelands, which once encompassed more than 200,000 square miles. They had quit hundreds of villages with apartment buildings containing 50 to several hundred rooms and thousands of hamlets with buildings containing fewer than 50 rooms.

They had vacated the marginal agricultural lands of the basin and range country of southern Arizona, southern New Mexico, western Texas, northern Chihuahua and northern Sonora. They had left the stream-dissected mesas and arid grasslands of the Colorado Plateau virtually uninhabited. Some, probably weary of the Pueblo urban environment, apparently retreated to the simpler ancestral nomadic lifestyle of hunting, foraging and incidental farming. Others, perhaps hungry for Pueblo urban and spiritual renewal, had migrated, after long odysseys as refugees in the desert, to emerging acculturated communities near river drainages and richer soils.

A New Land, A New Life

By the 16th century, in the southwestern United States, Puebloan peoples had congregated in some 100 restless and changing communities, most within the upper drainage basins of the Gila River, the Little Colorado River and the Rio Grande. These included the villages of the Zuni, on the Zuni River in west central New Mexico, near the Arizona border; the Hopi, on the southern escarpment of Black Mesa, in northwestern Arizona; the Acoma and Laguna, in the arid sculpted canyon and mesa country of west central New Mexico; and the eastern Puebloan peoples, along the main stream and tributaries of the Rio Grande, in north central New Mexico.

New immigrant populations confronted unfamiliar landscapes, new neighbors and differing traditions. They not only had to build new homes and break new fields, they had to reinvent themselves culturally and collectively in terms of their fundamental beliefs, language, political and organizational structures, religion and ceremony, architecture, arts and crafts and trade relationships.

Community Layouts

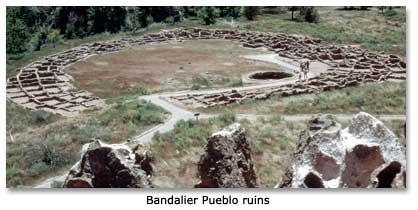

Across their redefined homeland, the Puebloan communities, sometimes with populations exceeding 2000 people, built apartment complexes, or "roomblocks," adjacent to open spaces, or plazas. They used the apartments, some with more than 2000 rooms, for ritual, work, living and domestic and community storage. They used the plazas for ceremonial stages and as common areas. They broke and irrigated nearby fields to raise the traditional food crops of corn, beans and squash. They hunted and foraged for game and wild plants to supplement their harvests. They may have fought raiders to defend homes, families and resources.

Beliefs

Although the galaxy of stories connected to the Creation, man’s origins, deities and tribal histories varied from community to community, the Puebloan peoples believed universally that a supreme supernatural being gave birth to the universe. They held that man emerged, guided by a deity or deities, from a phantasmagoric existence in three levels of underworlds to a new life on the surface of the earth. As commanded by their Creator, they felt committed to migrate from location to location through time until they finally found the center of the universe, where they would live thereafter.

The Zuni, for instance, attributed the creation of all things to "the Maker and container of All, the All-father Father, who existing alone in the void of dark space, conceived the waters, mists and streams, and then thought them into being," according to Pat Carr in her 1979 monograph Mimbres Mythology. "He made himself into the Sun to give light to the spaces and the waters, and then created the Mother-Earth and Father-Sky." (The Zuni belief about the Creation reminds of the Book of Genesis: "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters. And God said, ‘Let there be light’ and there was light.")

The Zuni thought that man emerged from an underworld which was populated with "unfinished creatures, crawling like reptiles one over another in filth and black darkness," according to legendary anthropologist Frank Hamilton Cushing. (See his paper "Outlines of Zuni Creation Myths" in the Bureau of American Ethnology, 16th Annual Report, 1891-2.)

Telling the story of man’s escape to the earth’s surface in the book Earth Fire, which he co-authored with linguist Ekkehart Malotki, Hopi Michael Lomatuway’ma said, "We emerged from the underworld [through a sacred aperture, or "sipapu"] at the Grand Canyon with many races of people and then migrated in all directions.

"The being who first inhabited this upper world gave us explicit instructions… Tradition has it that we first undertook a long migration before arriving here in Hopi country. Along the way we left many structures that still exist as ruins… Our destination was a place called Tuuwanasavi or ‘Earth Center,’ and only after reaching this place were we to settle for good."

According to some versions, the Creator dispatched the fabled "Hero Twins," or "War Twins," who had roots in Mesoamerican mythology, to draw the Puebloan people up through the sipapu and onto the earth’s surface. The twins would remain among the Puebloans to become some of the most revered of all in the pantheon of deities. Relying on magical powers, guile and courage – virtues cherished by the Puebloans – the twins, full of mischief, outwitted and defeated monsters and giants—metaphorical enemies of the Puebloans.

The twins "grew up to astounding adventures and achievements," said Southwest journalist Charles F. Lummis in his 1894 book, Pueblo Indian Folk Stories. "While still very young in years, they did very remarkable things; for they had a miraculously rapid growth, and at an age when other boys were toddling about home, these Hero Twins had already become very famous hunters and warriors.

"South of Acoma, in the pine-clad gorges and mesas," the Hero Twins killed a monstrous and supernaturally fearsome "She-Bear" when one of the twins "crept up very carefully and threw in her face a lot of ground chile, and ran. At that the She-Bear began to sneeze, ah-hutch! ah-hutch!. She could not stop and kept making ah-hutch until she sneezed herself to death.

"Then the Twins took their thunder-knives and skinned her…"

The Puebloans associated the cardinal directions with certain deities, colors, animals, plants and colors, according to Edward P. Dozier, The Pueblo Indians of North America. For example, the Pueblo communities associated north with the mountain lion, south with the wildcat (or, in some instances, the badger), east with the wolf and west with the bear.

The Puebloans viewed life in terms of binary or paired oppositions, for instance, summer and winter, hot and cold, day and night, strength and weakness, health and sickness, according to Dozier. (The Puebloan perspective of existence resembles the ancient Chinese concept of Yin and Yang, "dependent opposites" used to describe and explain the universe.) Rio Grande communities even divided their populations into two separate but equal groups (anthropologists call such organizational divisions "moieties"), for example, Winter People and Summer People, Ice People and Sun People or East Side People and West Side People.

The Puebloans’ beliefs and world views ran as undercurrents through their community organizations, celebrations, structures and art.

Puebloan Languages

By the time the Spanish arrived, the Puebloans had already consolidated into village groupings defined by language. The Zuni communities spoke the Zuni language, which bears no clear relationship to any other known language. Linguists call such a disconnected language an "isolate." The Hopi spoke the Hopi language, one of the Uto-Aztecan tongues spoken widely at the time in Mexico and the southwestern United States. The Acoma and Laguna Puebloans spoke a dialect of the Keresan language, also an isolate, and the communities on the Rio Grande drainages between the Jemez and Sandia Mountain ranges spoke another dialect of Keresan. The other communities within the Rio Grande drainage basin spoke various dialects (for example, Tiwa, Tewa, Towa, Tompiro and Piro) of the Aztec-Tanoan language group, which apparently had roots in Mesoamerican Mexico and the southwestern United States.

Social Organization, Religion and Ceremony

By the 16th century, the Puebloans had integrated their communities with revamped organizational structures, cementing their unity with a call to religious celebration, a veneer of ethnocentric pride and a spirit of independence.

In the pueblos within the Zuni, Hopi, Acoma and Laguna areas, families belonged to clans, the key organizational units of the communities, according to Dozier. Families traced clan affiliations and lineage through the women, who held ownership of home and land rights. Families within a household lived in adjoining rooms, and married men lived in their wives’ family homes. No one could marry within his or her birth clan. The most respected family within a clan usually held the responsibility for direction of the organization’s religious ceremonies, preservation of ceremonial lore and custodianship of ritual possessions.

Ceremonial brotherhood or sisterhood associations, closely associated with clans, orchestrated much of the religious life of a pueblo, appealing to supernatural powers for rain, bountiful harvests, successful hunts, miraculous cures and community harmony.

Community kachina masked dancing cults, apparently founded by religious leaders in the wake of the mass abandonments and migrations of the 14th and 15th centuries, emerged as the paramount ceremonial force, possibly as a means of reviving hope in dispirited refugee populations. The Puebloans equated a kachina with an ancestral spirit, who was charged with petitioning the deities for rain and prosperity. They believed that when Kachina chiefs and performers covered their faces with masks (called "friends"), they actually became the ancestral spirits. Kachina dancers – all men, initiated into the order – choreographed and rehearsed their roles in their ceremonial chambers, or kivas, and they performed the ceremony, punctuated with powerful drama, in the pueblo plaza. The kachina masked dancing cults, depicted in the media of kiva murals and apparently rock art, may have had some inspiration from Mesoamerica. Kachina masks often have goggle eyes and snarling mouths, much like those found in images of the ancient Mesoamerican storm god deity Tlaloc. Ceremonial dress bore symbols such as terraced rain altars and step-fret designs, much like those found on the facades and murals of Mesoamerican architecture.

In the Zuni, Hopi, Acoma and Laguna areas, the clans, religious associations and kachina masked dancing cults served to integrate and unify the communities. Among the Rio Grande drainage pueblos, the clans faded or virtually disappeared from community social structures, giving way to stronger nuclear and extended families, according to Dozier. The dual organizations called moieties collaborated with specialized religious and civic associations to integrate, unify and direct community life. Kachina cults, derived from the western Pueblo cults, played more marginal roles in the Rio Grande pueblos.

The Rio Grande pueblo associations and kachinas called on their deities not only to assure rain, prosperity, good health, successful hunts and community harmony, they also sought supernatural protection and reinforcement in battle, probably against raiding tribes from the neighboring plains to the east. (While they probably fought with the Plains tribes, the northernmost Rio Grande Puebloan communities also established trade relationships with them.)

Architecture, Arts and Crafts

By the 16th century, Puebloans had not only walked away from much of their Mogollon, Hohokam and Anasazi ancestral land, moved to new and larger communities, and established new institutions for religion and governance, they had re-shaped old icons and symbols into new architectural features, new designs and new patterns.

They expressed their new diversity, for example, in the construction of ceremonial kivas, the ancient heart of Puebloan religious life. In some villages, the residents built circular semisubterranean community kivas in the plazas and small circular clan or family kivas within apartment room blocks. It other villages, they built only small circular or rectangular kivas, some semisubterranean, others surface level. In a few villages, they built large circular semisubterranean kivas with no roofs. In still other villages, they built no kivas at all. In some instances, religious associations or kachina cults painted murals on kiva walls, but in no village did they build kivas as architecturally elaborate as, for instance, the 40- to 70-foot diameter semisubterranean Chaco Canyon Great Kivas with banquettes, pilasters, altar rooms and vaults.

Reviewing the centuries of abandonment, migration and resettlement, Linda Cordell said, in her book Archaeology of the Southwest, Second Edition, that, "If there is one pattern that all who work on this period of adjustment recognize, it may be summed up in the word crystallization. That is, many of the specific forms, designs, symbols, or motifs can be traced to much earlier periods, but in the fourteenth century, they came together in new ways, forming new patterns… There is little that is completely novel to this period. Rather, the organization of elements and their crystallization into new patterns constitute the innovation."

Community Pride

Across the Puebloan world of the 16th century, villages had not only synthesized or abandoned Mogollon, Hohokam and Anasazi roots, they had assumed a sense of bonding and even superiority, a characteristic which would endure into the 20th century. "The Pueblo Indian is quite ethnocentric about his pueblo," said Dozier, "and considers it the ‘center’ of the universe. Language, appearance, ceremonials, anything that may be compared or evaluated is at its best in one’s own pueblo. Other Pueblo Indians, even those of the same language group: speak funny; dance crudely; are without religious devotion…"

If, however, the Puebloan peoples of the time thought they had at last settled down, found their "center places," they would soon discover that a new and incomprehensible change had just begun.

The Arrival of the Spanish

For into the Puebloan world of the 16th century strode the Spaniards, a transcendent new force in the desert. They sought immediate wealth, empire, lost souls, adventure, new homes and long-term opportunity. They may have felt an urgent need to succeed because their nation was growing increasingly desperate for gold and silver to finance its worldwide empire, its aristocratic extravagance, its religious zeal and its European wars.

Reporting to their viceroy and the Crown about the Puebloan southwest, the Spanish spoke of cities of gold and villages of stone and mud; ceremonial arrowheads of emeralds and crystals of salt; mines with precious metals and mountains of sterile soil; scenes of Indian salvation and kiva murals of "demon" gods; people of kindness and generosity and warriors like "crouching tigers;" mountains with snowy peaks and desert sands with no water; abundant stores of food and cotton cloth and the prospect of starvation.

Failing to find new kingdoms with treasuries filled with gold and silver, like those of the Aztecs and Incas, the Spaniard settlers of the southwestern United States set their sights on the expansion and consolidation of the empire of the crown, the conversion of the Puebloan peoples into Spanish Catholic subjects, and the establishment of new communities and farms in a promising new land. Eleven hundred miles from Mexico and an eternity from Madrid, it would not be easy.

"Paleo-Indians" (Part 1)

Desert Archaic peoples( Part 2)

Desert Archaic peoples - Spritual Quest (Part 3)

Native Americans - The Formative Period (Part 4)

Voices from the South (Part 5)

The Mogollon Basin and Range Region (Part 6)

The Mogollon - Their Magic (Part7)

Hohokam the Farmers (Part 8)

The Hohokam Signature (Part 9 )

The Anasazi (Part 10)

The Anasazi 2 (Part 11)

The Great Puebloan Abandonments (Part 12)

Paquime (Part 13)

When The Spanish Came (Part 14) This page

Life on the Margin (Part 15)

Life on the Margin (2) (Part 16)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 1 (Part 17)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 2 (Part 18)

The Outside Raiders (Part 19)

The Enduring Mysteries (Part 20)

Some Sites to Visit (Final Part)

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms

SEARCH THIS SITE

Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park

The movie Stagecoach, in 1939 introduced two stars to the American public, John Wayne, and Monument Valley. Visiting Monument Valley gives you a spiritual and uplifting experience that few places on earth can duplicate. Take a look at this spectacular scenery in this DesertUSA video.

Glen Canyon Dam - Lake Powell Held behind the Bureau of Reclamation's Glen Canyon Dam, waters of the Colorado River and tributaries are backed up almost 186 miles, forming Lake Powell. The dam was completed in 1963. Take a look at this tremendous feat of engineering - the Glen Canyon Dam.

Canyon de Chelly National Monument

Canyon de Chelly NM offers the opportunity to learn about Southwestern Indian history from the earliest Anasazi to the Navajo Indians who live and farm here today. Its primary attractions are ruins of Indian villages built between 350 and 1300 AD at the base of sheer red cliffs and in canyon wall caves.

___________________________________

Take a look at our Animals index page to find information about all kinds of birds, snakes, mammals, spiders and more!

Click here to see current desert temperatures!