Ancient Civilizations - Native Americans

Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, Toltec, Tarascan and Aztec

La Quemada, example of ancient southern Mexico and Central America architecture.

The great civilizations of ancient southern Mexico and Central America – or Mesoamerica – where names such as Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, Toltec, Tarascan and Aztec are written into a 3500-year history, left distinct fingerprints on the cultures of the Indians of the deserts of the southwestern U. S. and northern Mexico.

The definition of the complex and differing cultural debts which the various Indian cultures of the desert owe to the peoples of Mesoamerica remains one of the overarching – and most contentious – problems in the archaeology of southwestern North America. We do know, of course, that the Mesoamerican civilizations, which rose to the pinnacle of all the prehistoric cultures in North America, cast a long and influential shadow.

The Mesoamericans

During the time between about 2000 B. C. and the sixteenth century (the time of the Spanish Conquest), the Mesoamericans founded a succession of city-states, and they defined their history in terms of imperial capitals, satellite villages, a stratified social structure, monumental ceremonial architecture, religion, warfare, conquest, human sacrifice, agriculture, artisanship and a wide-spread trade network.

The ruling elite, with a retinue of nobles, high priests, shamans, warrior captains, politicians, administrators and other officials, lived in imperial capitals, for example, Teotihuacan (approximately 100 B. C. to A. D. 700) with a population of more than 100,000 and Tenochtitlan (A. D. 1325 to 1521) with a population of some 200,000. Commoners lived within city apartment complexes or in outlying villages. In the hearts of their capital cities, the Mesoamericans constructed well planned complexes of step-sided pyramids, colonnaded temples, single-story palaces and ceremonial avenues. They embellished monuments to  their beliefs, rituals and social classes with sculptures of brooding figures and panels of icons and complex step fret designs.

their beliefs, rituals and social classes with sculptures of brooding figures and panels of icons and complex step fret designs.

The Mesoamericans immersed themselves in religion, which they regarded as the medium of life. They celebrated in ritual and dance the change of the seasons and the ordered march of time. They vested supernatural power in places such as mountain peaks, sequestered springs and secreted caves; natural phenomena such as cloud formation, rain, lightening, wind, fire and earthquakes; and "sky wanderers" such as the sun, the moon, planets (especially Venus), various stars and the Milky Way.

They held wild creatures to be sacred, especially the eagle, for example, which represented the promise of the celestial; the serpent, which linked them to the earth; the jaguar, a symbol of raw power, which became a god of the underworld; the rabbit, which became the special pet of the moon goddess (the Maya saw the shape of a rabbit rather than the face of a man in the full moon); and the hummingbird, which taught the Tarascans to weave sacred straw figures. They associated feathers, especially those of the more exotic and colorful tropical birds such as the macaw and parrot, with the flight of thought and imagination.

They connected themselves to a pantheon of deities through elaborate and carefully orchestrated ritual. They offered their deities their blood and treasure, and they called on  them, not only to account for creation and destiny, but also to assure renewal, nurture, balance, order and unification of their social system and environment. For example, the Maya’s Hero Twins – pictured as two figures rendered in ceramics, bas relief and murals – outwitted evil gods and monsters and brought renewal in return for sacrifice. The Toltec’s Tlaloc ("He Who Makes Things Sprout") – represented by a goggle-eyed, snarling face carved into architectural facades – brought rain to crops in return for sacrificed children. The Aztec’s Quetzacoatl deity – symbolized by a plumed, or feathered, serpent, carved into facades – played a key role in the creation, then the re-creation, of heaven, earth and human beings. In return for sacrifice.

them, not only to account for creation and destiny, but also to assure renewal, nurture, balance, order and unification of their social system and environment. For example, the Maya’s Hero Twins – pictured as two figures rendered in ceramics, bas relief and murals – outwitted evil gods and monsters and brought renewal in return for sacrifice. The Toltec’s Tlaloc ("He Who Makes Things Sprout") – represented by a goggle-eyed, snarling face carved into architectural facades – brought rain to crops in return for sacrificed children. The Aztec’s Quetzacoatl deity – symbolized by a plumed, or feathered, serpent, carved into facades – played a key role in the creation, then the re-creation, of heaven, earth and human beings. In return for sacrifice.

Divine leaders pulled the levers of power (often seated in a highly centralized bureaucracy) to make and enforce laws, implement public projects, tax citizens and raise military forces. They waged war in quest of empire, commerce, resources, tribute, prestige, slaves and sacrificial captives (who yielded up their lives at ceremonial altars to satisfy the blood lust of Mesoamerican deities). They orchestrated ritualized high-stakes games played with rubber balls in I-shaped ball courts, where winners gained acclaim and adulation and losers forfeited their heads.

The Mesoamericans built an economy based on irrigation agriculture, craftsmanship and trade. Although they raised a number of crops, they regarded corn as the sacred heart of their fields, a metaphor for life, a gift from the gods. They manufactured a broad diversity of products, including, for instance, obsidian tools, ceramic vessels and effigies, woven cotton textiles, bark paper and elegantly painted manuscripts. They trekked well-established trade routes, which Spanish expeditions would someday follow across the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts to the north, to exchange religious beliefs, ideas, crafts, myths, icons, macaws, parrots, feathers, pyrite mirrors, copper bells and shells in return for obsidian and the sacred stone, turquoise.

The Contrast in Cultures

Years ago, my wife, Martha, and I, and our long-time friends and traveling companions, Tom and Debbie O’Loughlin (both archaeologists), explored the five T-shaped platform temple mound ruins at Mexico’s Tzintzuntzan (approximately A. D. 1100 to 1530). The mounds extend for more than a quarter of a mile along the northeastern shore of the beautiful and placid (although now distressingly polluted) Lake Patzcuaro, west of Mexico City. Tzintzuntzan had once been the capital of the Tarascans, one of the most powerful peoples in the Central Highlands of Mexico when the Spanish arrived. From atop the massive structures, looking across the lake, we thought about how the Tarascans once overran their neighbors in campaigns for empire, gold, copper, cotton, salt, feathers and slaves; fought epic battles with the Aztecs, leaving the field littered with thousands of dead and wounded; mastered the crafts of working with gold and copper as well as ceramics, textiles and precious minerals; and treated the delicate hummingbird as a deity. In fact, the word "Tzintzuntzan" means "Place of the Hummingbirds" in Tarascan. The very name mimics the sound of the hummingbird in flight.

We contrasted in our mind’s eye the monumental ruins of the Tarascans on Lake Patzcuaro with the ruins of the Indians of the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts, where we often find no more than the dwelling depressions or melting adobe or crumbling stone walls of small hamlets lying near tenuous streams, intermittent washes and playas. We knew that the desert peoples never built monumental pyramids to honor their deities nor contested for great empire nor fought prodigious battles with their neighbors. (Indeed, archaeologists usually find relatively little evidence of weaponry and warfare in the desert ruins.) We knew that they never perfected the technology for fashioning gold into elegant ornaments. Once, however, during a trip in far western Texas with archaeologist Scotty MacNeish (who traced the origins of corn in Mesoamerica), we climbed to the top of a large boulder which was covered with pecked and scribed prehistoric images. On the very crest, we discovered, carved carefully into the stone surface, the figure of a hummingbird.

Mesoamerican Fingerprints

The Mesoamericans influenced the Indians of the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts most profoundly through the introduction of agriculture, although the notion of growing crops, rather than hunting and gathering, for food and resources took hold fitfully, with glacial slowness, before it led to the regional transition from nomadic hunting and gathering to settled villages, more substantial housing and cultivated fields. While they raised beans and squash and other crops with origins in Mexico, the Indians of the desert – like the peoples of Mesoamerica – associated corn with life. They celebrated it in dance, ritual, story and art. Among the western Pueblos, for instance, it is the "Corn Maidens" who hold special honor and veneration because they rescued the people from starvation, and they appear in seasonal ceremonies, tribal histories, ceramic designs and sacred murals.

In addition to agriculture, the Mesoamericans almost certainly introduced the craft of producing pottery to the peoples of the desert, roughly at the same time that the Christian era began, and although it had less cultural impact than corn, ceramics have become important cultural markers for locations and times in the prehistory of the southwestern U. S. and northern Mexico.

While archaeologists can follow the development and spread of agriculture and ceramic technology across the desert, they have found that tracing the threads of other Mesoamerican introductions comes much harder, even with a kaleidoscope of intriguing clues.

In the Mogollon region, which extends from southeastern Arizona across southern New Mexico, western Texas and northern Chihuahua, a number of the galaxy of ancient rock paintings at the Hueco Tanks state historical park (about 35 miles east of El Paso) resonate with influences from the south. There we find images of geometric designs which appear to relate to Mesoamerican motifs; corn, which signifies the sacred importance of the crop to prehistoric villagers, echoing the spiritual value of corn in Mesoamerica; step-sided pyramids, or rain altars, which recall the monumental architecture of the Mesoamericans; a stylized cat, which may tie to the Mesoamerican jaguar deity; eerie goggle-eyed figures, which almost certainly descended from the Mesoamerican god of storms, Tlaloc, "He Who Makes Things Sprout;" a Horned Serpent, which owes its roots to Quetzacoatl, the Plumed Serpent of Mesoamerica; and a conical headdress crowned by a Horned and Plumed Serpent, which suggests a transition between the Quetzacoatl-type figures of Mesoamerica and the desert.

In the Mogollon region, which extends from southeastern Arizona across southern New Mexico, western Texas and northern Chihuahua, a number of the galaxy of ancient rock paintings at the Hueco Tanks state historical park (about 35 miles east of El Paso) resonate with influences from the south. There we find images of geometric designs which appear to relate to Mesoamerican motifs; corn, which signifies the sacred importance of the crop to prehistoric villagers, echoing the spiritual value of corn in Mesoamerica; step-sided pyramids, or rain altars, which recall the monumental architecture of the Mesoamericans; a stylized cat, which may tie to the Mesoamerican jaguar deity; eerie goggle-eyed figures, which almost certainly descended from the Mesoamerican god of storms, Tlaloc, "He Who Makes Things Sprout;" a Horned Serpent, which owes its roots to Quetzacoatl, the Plumed Serpent of Mesoamerica; and a conical headdress crowned by a Horned and Plumed Serpent, which suggests a transition between the Quetzacoatl-type figures of Mesoamerica and the desert.

At least one researcher – Kay Sutherland, a cultural anthropologist with St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas – suspects that Hueco Tanks may have been the birthplace of the western Pueblos’ katchina dance cults, with masks having evolved from depictions of the Tlaloc deity. Other scholars dispute that notion, insisting that the katchinas emerged from farther north, under different circumstances.

In a small cave southeast of Hueco Tanks, north of the village of Fort Hancock, Texas, we find intriguing rock paintings of a jaguar, a Horned Serpent and Tlaloc. In another cave, this one northeast of Hueco Tanks, just north of the Texas/New Mexico border, we find an especially haunting figure of the Tlaloc deity. At the Three Rivers site, on the western flanks of the Sacramento Mountains in central New Mexico, we find pecked in the stone a ceremonial figure with a tablita headdress and a cornstalk staff or wand.

On the famed story-telling mortuary bowls of the Mogollon Mimbres branch (A. D. 1000 to 1150), who lived along the valleys of the rough mountain areas in southwestern New Mexico, we find images with a heritage in Mesoamerica and roles in historic western pueblo tribal histories. In the inner surfaces of their bowls, fanciful and creative Mimbres potters produced the figures of rabbits (clearly the black-tailed jackrabbit), the ancient pets of the Maya moon goddess, huddled with arched backs, as though poised for flight, and in at least one instance, a rabbit resting on a crested moon; parrots, native to tropical Mesoamerica, with their importance in Mimbres culture reinforced by the elegance of design and the exceptional quality of the drawing; apparent Hero Twins, deities who play out mythological roles in outwitting and defeating evil gods and monsters; an apparent Tlaloc – He Who Makes Things Sprout – mounted on the tip of a "paho," or prayer stick, in a dance ceremony; and the Horned Serpent, or Quetzalcoatl, figure incorporated into design motifs or incorporated as headdresses and cloaks for Hero Twins and shamans.

In her 1979 Mimbres Mythology, Southwestern Studies, Monograph No. 56, Pat Carr said, "At the end of the tenth century, about the time of the appearance of the Mimbres potters, the cult of the Plumed Serpent, Quetzalcoatl, got new impetus in the Toltec-Chichimec city of Tula. …perhaps it is not mere coincidence that in the Pueblo area, the mythic Water Serpent [Horned Serpent] was the one who nourished germs and seeds and who furnished liquid in the form of sap to plants and blood to animals."

In the Hohokam region, which covers most of Arizona and extends southward into Sonora and northwestern Chihuahua, there is such an apparent veneer of Mesoamerican influences that some early researchers thought, probably erroneously, that Mesoamerican colonists had founded the early settlements. The Hohokam constructed relatively large communities – for instance, Snaketown, located on the Gila River, between Phoenix and Tucson – with populations of more than 1000 people, and inspired by the Mesoamericans, they built special structures, "Great Houses," presumably for the pleasure of the elites. They raised earthen platform mounds, which apparently served as bases for temples or elite residences and the centerpiece for ceremonies. The largest of the mounds would have covered a modern football field, and it stood 25 to 30 feet high. In Arizona alone, the Hohokam constructed more than 200 ball courts, excavating oval depressions which averaged perhaps 100 feet in length and 50 feet in width. One ball court at Snaketown measured more than twice the average size, and it would have accommodated hundreds of spectators along the banks on either side of the playing surface.

(Ball courts even occurred in the Mogollon area. In the "boot heel" of southwestern New Mexico, Bill Walker, New Mexico State University archaeologist, and his students, have excavated rudimentary Mesoamerican-style ball courts on the desert floor.)

The Hohokam raised the traditional corn, beans and squash plus cotton and a number of other crops in Gila and Salt River basin fields, which they irrigated with a network of more than 500 miles of canals measuring from 6 to 60 or 70 feet across. The Hohokam built the canal system between A. D. 300 and 1450, moving more than 1,000,000 cubic yards of earth during the construction. Like the Mesoamericans, the Hohokam wove cotton fibers into textiles; molded and fired clay into vessels and figurines; and shaped stone into effigy vessels, beads, ear plugs, nose buttons and palettes. They traded with the Mesoamericans for macaws, copper bells, pyrite mirrors and sea shells.

At least one archaeologist, Steven Shackley, Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California at Berkeley, thinks that the Hohokam projected their influence westward across the Colorado River clear to the Pacific Coast, and he suggests that the Hohokam may have encompassed the Patayan group, which occupied both sides of the Colorado River basin from northern Arizona and southeastern Nevada to the Sea of Cortez.

In the land of the Anasazi, anchored by the fabled ruins at Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico, the Pueblos gave expression to the Mesoamerican influence, not only in rock art and ceramic designs, but also in their architecture, trade goods, spirituality and ritual dance.

In discussing architectural similarities in their 1981 book Chaco Canyon, Robert and Florence Lister, said, "…the list of Mesoamerican traits [in Chaco Canyon ruins] has grown longer and now includes such architectural features as rubble-cored masonry [stone rubble encased in stone masonry], square columns used in colonnades, circular structures in the form of tower kivas and tri-walled units, seating discs beneath roof support posts, and T-shaped doorways…" They also point out that, "…the alignments of architectural and other features for the purpose of observing and recording astronomical data, all of which have been noted in Chaco Canyon, are much more common in central Mexico."

Mesoamerican trade goods at Chaco, say the Listers, include such things as copper bells, iron pyrites, shell trumpets, shell beads, shell bracelets, macaws and parrots. "Acquisition of turquoise, and perhaps other goods desired by the Mexican traders, was intensified," said the Listers, "and stockpiles were assembled in the Chaco towns." Mesoamerican demand triggered intensive turquoise mining at sites such as the Cerrillos Mountains a few miles southwest of Santa Fe. Turquoise from mines in the desert southwest now serve as trail markers in sites along the Mesoamerican trade routes.

Spiritual icons such as the Hero Twins, Tlaloc and Horned Serpent figures declare their parentage, and they seem to have played roles in Anasazi beliefs which evolved from those in Mesoamerican cultures. For instance, J. J. Brody, a distinguished researcher in Native American Art History and past Director of the University of New Mexico’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, said in his book Mimbres Painted Pottery that the Horned Serpent, "…may be identified with the Mexican deity Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent… Much altered and in a variety of manifestations, these Mesoamerican deities became important to late Anasazi and historic Pueblo people.

"Ideological relationships to Middle America and Mesoamerica were manifested in many ways," Brody said, "and seem to have been intermittently active from time immemorial."

In ritual dances of Pueblos (descendants of the Anasazi), the choreography sometimes still reflects Mesoamerican roots. In one dance, for instance, the performers, arms linked behind their backs, dance gracefully in two long lines, closely mimicking a dance the Aztecs performed to honor Montezuma. In his Book of the Hopi, Southwest author Frank Waters said that the "ripe richness, grotesque imagery and barbaric beauty of Hopi ceremonials…parallel the meanings and often the exact rituals of the ancient Aztecs, Toltecs and Maya."

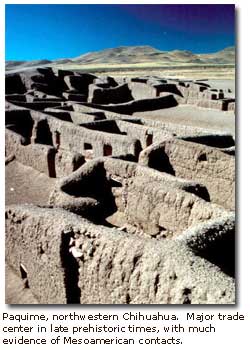

In the last centuries before the arrival of the Spaniards, Paquime, the large and influential pueblo in northwestern Chihuahua, acquired so many imprints from the south that some archaeologists have regarded it as a Mesoamerican outlier, possibly a regional trade center. Spiritual icons, effigy mounds, I-shaped ball courts, water control systems, trade goods, scarlet macaws, crafts all speak to a strong interaction with Mesoamerica.

The Question Still Remains

For all the evidence, archaeologists may never be able to gage how deeply the Mesoamerican currents truly ran through the cultures of the southwestern U. S. and northern Mexico. Over time, the Indians of the desert did accept agriculture, but they adapted it to their arid environment. They continued hunting and gathering to supplement their food and resources. They learned Mesoamerican crafts, for instance, pottery making, but they put their own stamp on their products. They developed some social stratification, but they never seem to have celebrated it, for instance, with images or statuary of divine leaders, in the manner of the Mesoamericans. Some built sacred structures, for example, platform and effigy mounds, but they never constructed monumental religious complexes with pyramids, palaces and ceremonial boulevards. They held certain places, natural phenomena, planets and stars, and animals to be sacred, but many prehistoric peoples, for instance, the profoundly spiritual Plains Indians, also believed much of their world to be sacred. The Indians of the desert adapted some important Mesoamerican religious icons and concepts, but they apparently modified them, molding them and integrating them into their own hunting and gathering belief system (much like the Pueblos combined Catholic beliefs and ritual with traditional religious practices when the Spanish came). They appear to have offered their pantheon of deities little if anything in the way of human sacrifice—a bloody staple of Mesoamerica. They migrated frequently, abandoning old villages and establishing new ones, but not, apparently, in the name of conquest and empire. They owed a cultural debt to Mesoamerica, but they bent it through the prism of their hunting and gathering past, which the Indians of the desert still recall in their modern lives and ceremony.

My wife and I once stopped to visit the exquisitely decorated Catholic mission church at the Laguna Pueblo, west of Albuquerque. Unexpectedly, at the front door, we heard the sounds of celebration within the sanctuary. A Laguna woman invited us to step inside. She whispered, "We’re honoring one of our nuns, who has served here for 20 years." From just inside the door, we watched with delight as Laguna men and women in traditional dress danced before the altar to the beat of a tribal drum, paying tribute to a beloved woman in the old Indian way.

For additional information, consult: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 9, Southwest, "Agricultural Beginnings, 2000 B. C. - A. D. 500," by Richard B. Woodbury and Ezra B. W. Zubrow; An Introduction to American Archaeology, Volume I, by Gordon R. Willey; Archaeology of the Southwest by Linda Cordell; Chaco Canyon by Robert and Florence Lister; Mimbres Mythology, Southwestern Studies, Monograph No. 56, by Pat Carr; and Mimbres Painted Pottery by J. J. Brody. These sources should be found in any university library.

You can learn more about the early farmers of the desert from the Woodbury and Zubrow paper (the major source for this article) and from Gordon R. Willey’s An Introduction to American Archaeology, Volume One, and Polly Schaafsma’s Indian Rock Art of the Southwest.

"Paleo-Indians" (Part 1)

Desert Archaic peoples( Part 2)

Desert Archaic peoples - Spritual Quest (Part 3)

Native Americans - The Formative Period (Part 4)

Voices from the South (Part 5) This page

The Mogollon Basin and Range Region (Part 6)

The Mogollon - Their Magic (Part7)

Hohokam the Farmers (Part 8)

The Hohokam Signature (Part 9 )

The Anasazi (Part 10)

The Anasazi 2 (Part 11)

The Great Puebloan Abandonments (Part 12)

Paquime (Part 13)

When The Spanish Came (Part 14)

Life on the Margin (Part 15)

Life on the Margin (2) (Part 16)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 1 (Part 17)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 2 (Part 18)

The Outside Raiders (Part 19)

The Enduring Mysteries (Part 20)

Some Sites to Visit (Final Part)

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Your GPS Navigation Systems

May Get You Killed

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Desert Survival Skills

- Successful Search & Rescue Missions with Happy Endings

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert

Survival Tips for Horse and Rider

- Preparing

an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms