Mogollon

Basin and Range People

As the desert Indians of the Formative Period (early first millennium to late prehistoric times) emerged from their hunting and gathering past and turned increasingly to a village and agricultural future, the three major groups – the Mogollon, the Hohokam and the Anasazi – all belonged to the same cultural congregation but they occupied differing environmental regions.

The Mogollon had to adapt to the forested mountain ranges and high Chihuahuan Desert basins of southeastern Arizona, southern New Mexico, western Texas, and northern Chihuahua and northern Sonora; the Hohokam and their cultural cousins, the Patayan, to the relentlessly hot Sonoran desert country of south-central and western Arizona, southeastern California and northern Sonora; and the fabled Anasazi, to the arid canyons and mesas of the Colorado Plateau. This meant, for example, that a Mogollon band which lived in a low mountain river valley in southeastern New Mexico and a Hohokam band which lived in the Sonoran Desert south of Phoenix had to adapt to differing growing seasons, temperature ranges, rainfall patterns, resources, and game and wild food plant communities. Each culture had to develop differing farming practices, technological capabilities, hunting strategies, gathering techniques and food preparation methods.

The Mogollon Basin and Range Region

In the Mogollon cultural region, the Indian communities occupied what may be the most geologically and ecologically diverse landscape in the United States.

The mountain ranges, with peaks as high as 12,000 feet in elevation, run north and south, roughly parallel, and they embrace the desert basins, with river valleys as low as 1000 feet in elevation. The land reflects the geologically recent torment of continental rifting, structural fracturing, volcanism, erosion and sedimentation. Much of the rubble and soil filling the basins washed down from the mountains during the much wetter times of past ice ages.

On the higher peaks, at elevations from about 9500 to 11,500 feet – the windiest, wettest and coldest environment in the Mogollon region – spruce and fir trees dominate, reaching the timber line and growing in dense stands along the banks of streams and the edges of alpine meadows. Several dozen other plants, including trees in the conifer family and shrubs with edible fruits, also appear in the zone. Annual precipitation ranges from 30 to as much as 90 inches, with winter snow drifts often lasting well into the spring or even early summer.

At 8000 to 9500 feet, the vegetation increases in abundance, with dense stands of dark-green Douglas fir mixed with the white-barked quaking aspen assuming the dominant role. Plants from higher and lower zones sometimes extend arms of growth into this band. Willows line streamsides, and lodgepole pines pioneer areas cleared by fire. Several shade-tolerant shrubs with edible fruits grow within the forest stands. Annual precipitation falls to 25 or 30 inches.

Between 6500 and 8000 feet – the lowest band of true forest in the region – the ponderosa pine and Gambel oak define the character of the plant community. Again, plants from the higher and lower belts wander into this range. About four dozen plants, several with edible fruits, grow only in this region. Annual precipitation declines to 20 to 25 inches.

Between 4500 and 6500 feet – the usually dry and rocky zone which separates the mountain forests from the desert basins – drought-resistant and slow-growing pinyon pine and one-seed and alligator junipers take center stage, forming "dwarf" or "pygmy" forests. Cacti, yuccas, Apache plumes, saltbush, greasewood and numerous other plants from the desert reach up into the zone. In good years, the pinyon pine cones yield an abundance of nutritious nuts—a crucial food source in prehistoric times. Desert-like annual precipitation ranges from 10 to 20 inches.

The desert basins, dissected by mountain washes and streams and by a very few rivers, lie between the elevations of 1000 and 4500 feet. They comprise a mix of desert grasslands, various scrub brushlands, mesquite dunelands, sand dunefields, lava flows, playas (shallow lake beds) and river basins. Black gramma, creosote bush, tarbush, honey mesquite, soaptree and datil yucca, lechuguilla, ocotillo, common cholla, sotol, various prickly pear cacti, hedgehog cacti and numerous other species – many of them useful as food and resources to the Mogollon – form a crazy quilt of vegetation across the desert sands. Cottonwoods and willows formed dense woodland environments, or "bosques," along the banks of rivers and some drainages. Average precipitation now ranges from less than 8 to as much as some 12 inches, most of it falling in the July, August and September. Maximum summer temperatures hover near 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and winter temperatures can drop to well below freezing.

willows formed dense woodland environments, or "bosques," along the banks of rivers and some drainages. Average precipitation now ranges from less than 8 to as much as some 12 inches, most of it falling in the July, August and September. Maximum summer temperatures hover near 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and winter temperatures can drop to well below freezing.

In addition to wild edible and utilitarian plants, the mountain flanks and desert basins harbored a thriving community of game, including bighorn sheep, elk, mule deer, white-tail deer, antelope, beaver, badger, blacktail jackrabbits, desert cottontails, turkeys and various other species. Rock exposures served as quarries for the raw materials for making projectile points and tools. Clay exposures provided the raw material for making ceramic vessels and figurines.

Even as the Mogollon people gradually adopted village life and farming, they would continue to count on the ranges and basins to supplement their larder and provide essential material resources. They would never be able to rely on corn, beans, squash and other crops to the exclusion of wild plant foods because the Mogollon region held relatively few areas suitable for agriculture. Most of them occurred along lower mountain river valleys, along the few desert river basins and near a few desert playas. Even those areas which were suitable experienced erratic rainfall year in and year out.

The Mogollon Culture

Several Mogollon groups clustered within roughly 100 miles east and west of the New Mexico and Arizona border and extended some unknown distance southward into Chihuahua and Sonora. These westernmost groups – with their signature brownware ceramics – give definition to the Mogollon culture, but another group, closely related culturally and called the Jornado Mogollon, spanned another two hundred miles eastward, almost to the Great Plains, and some unknown distance southward, into Chihuahua. The Mogollon groups, widely separated in different environments, progressed at different rates through three basic phases of cultural development.

In the first phase, which began sometime around the start of the first millennium, the western groups probably still accepted agriculture somewhat grudgingly even though it had been around for at least 2000 years. Some lived in rock alcoves or caves. Others, probably extended families of a few dozen people, built small hamlets of scattered lodges atop easily defensible knolls, ridges and bluffs, overlooking their fields. They sometimes erected crude fortified walls to help protect their communities. They may have lived in fear of raids by nomadic bands who still clung to a predominantly hunting and gathering way of life.

The early Mogollon lived in semi-subterranean lodges, or "pithouses," which consisted of excavated holes typically covered by domed roofs. The holes, roughly circular in shape, measured two to five feet deep, with a diameter of 10 to 15 feet. The roofs, made of brush and grass with a thick mud plaster cap, rested either on four upright forked posts set in a square or on a single upright post set in the center and other posts set at the perimeter. A ramped crawlway or a stepped doorway served as an entrance.

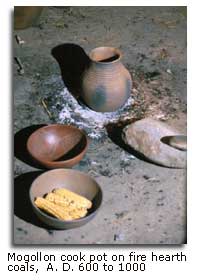

Some families built cook fires in the centers of their pithouses, sometimes in no more than a depression in the floor and other times in clay- or stone-lined hearths. Other families built their fires outside, although they may have carried fire-heated stones inside to radiate warmth into their lodges on cold winter nights.

Some families built cook fires in the centers of their pithouses, sometimes in no more than a depression in the floor and other times in clay- or stone-lined hearths. Other families built their fires outside, although they may have carried fire-heated stones inside to radiate warmth into their lodges on cold winter nights.

A typical family’s household possessions would include plain brown or reddish ceramic bowls, pots, jars and other vessels; yucca- or sotol-fiber woven baskets and cradles; grinding and crushing stones; fire drills and tongs; and grass beds, reed or straw mats, and feather or rabbit fur blankets. Individual possessions could include clothing made from animal skins or plant fibers; shoes and belts made from woven yucca fibers; pendants, necklaces, rings and bracelets made from shell, bone or semi-precious stones; awls, needles, fleshing tools, flaking tools and other tools made from bone; projectile points, drills, knives, choppers, axes and scrapers chipped from stone; and atlatl – spear-thrower – weights, balls, disks and pipes made from ground stone.

The Mogollon stored food, including grain from crops and seeds from wild plants, in bowl-sized to barrel-sized pits excavated inside or immediately outside their homes. They probably covered the floors of the larger storage pits with rough planking, and they capped the tops with flat stones. They sometimes buried family members, tightly flexed, in the large interior storage pits, and they continued to live in their lodge, above the remains.

In the heart of their hamlets, the Mogollon built larger semisubterranean structures which probably served as community ceremonial structures, or kivas. With roughly circular or D-shaped floor plans, the kivas, with ramped or stepped entrances, usually faced easterly. Perhaps all contained articles of ritual, for instance, clay effigies of humans or animals, prayer sticks of shamans, the claws of powerful animals, stone pipes for wild tobacco, colored mineral ingredients for body paints, crystals of quartz, and stones with exotic shapes. Most had central fire hearths. Some had interior storage pits. A few had parallel floor grooves, apparently formed by logs which might have provided mooring for tautly stretched animal hide foot drums.

In cadence with the seasons and with the inspiration of elaborate ritual, families planted corn, beans, squash, cotton and perhaps other crops along river banks, in washes and on bluffs, hoping that any failure in one location would be offset by success in another. Children likely watched over the crops, chasing away raiding rodents and birds. The Mogollon gathered their crops, presumably into their woven baskets, and carried them back to their villages for initial processing and caching. They celebrated good harvests with ceremony and joy.

hoping that any failure in one location would be offset by success in another. Children likely watched over the crops, chasing away raiding rodents and birds. The Mogollon gathered their crops, presumably into their woven baskets, and carried them back to their villages for initial processing and caching. They celebrated good harvests with ceremony and joy.

Hunting parties, armed with the traditional spears and atlatl’s in the earliest centuries and with bows and arrows in the latter centuries, killed mule deer along the mountain flanks and took buffalo, or bison, from the northern Chihuahuan Desert. (We usually think of buffalo as an animals of the plains, not the Chihuahuan Desert, but a few years ago, my wife, with a group of archaeologists, visited a prehistoric buffalo kill site in the heart of Mogollon country, a few miles north of our border with Mexico. Buffalo bones still litter the area.) The Mogollon hunters also trapped wild turkeys well up into the mountains, muskrat and beaver along the streams, and blacktail jackrabbits in the desert basins.

Gathering parties, equipped with woven baskets, ascended the mountains to harvest wild fruits and seeds. They likely picked currants and berries from alpine meadows; wild raspberries and elderberries in the Douglas fir and aspen forests; acorns, juniper berries, manzanita "apples" and chokecherries in the ponderosa pine and Gambel oak zone; pinyon nuts, acorns, grapes, mulberries and many other fruits from the pygmy forests. In the desert basins, they harvested the fruit and the roots of the yuccas, bloom stalks of the agave, the fruits and pads of the prickly pear cacti, the seed pods of the devilsclaws, the beans of the honey mesquite and the acorns of the shinnery oak. In both the mountains and desert basins, they gathered plant fibers and barks for use in manufacturing basketry, sandals, clothing and cradles.

In the mountains and deserts, medicine men and shamans collected plants they could use for medicines, for instance, ephedra, manzanita, barberry and ceanothus, or for vision-inducing narcotics, for instance, mescal and sacred datura.

Near the villages, we presume – we don’t know how the Mogollon people divided their work – that men and women both planted and harvested their crops, possibly directing water through small ditches to irrigate their fields.

We presume that the women gathered clay from nearby sources, coiled clay "ropes" into various vessel shapes, polished the moist surfaces with scapers and smooth stones, added minimal if any decoration on the brown or reddish surfaces, and fired the vessels in hot coals. We might also presume that the women, in a kind of gossipy community, used mortars and pestles and milling basins (metates) and hand stones (manos) to pound and grind grains and seeds into flour for cooking. We can imagine that they wove plant fibers, turning them into baskets, sandals and cradles, that they fleshed and cured hides, sewing them into clothing. We can assume that the women cared for the children.

We think of the men as excavating the pits for a new lodge, cutting and setting support posts, building and plastering the roofs. We see them flaking stone to make projectile points and tools; fashioning spears and atlatls and, later, bows and arrows; grinding stream cobbles to make ax heads. We can envision them training their sons in the use of the weapons, the language of the trail and the art of the hunt. We can see old men, no longer able to track a mule deer across the hard Mogollon country, sitting before their lodges in the late afternoon sun, smoking kinnikinnick (a mixture of leaves and bark of dogwood, bearberry, willow and wild tobacco) in ground stone pipes. We can imagine the steady chanting of a shaman in the village kiva.

We can visualize the rare trading party which might appear with packs full of bi-valve shells from the Gulf of California or pots from a distant village, and in our mind’s eye, we can see the excitement of the barter with the traders and the hunger for news about cultural brethren.

Having camped many times near Mogollon village ruins in southwestern New Mexico’s Gila Wilderness, near the Mimbres River, I know that after nightfall, the bands of that area could hear the sound of running water in the darkness, the gentle call of the whip-poor-will, the hoo-hoo-hoooo of the great horned owl, and the howls and yelps of hunting coyotes, and I know they could see the splendor of the Milky Way in the night sky.

In their second phase of development, which began after the middle of the first millennium, the western Mogollon bands apparently felt less threatened by their enemies, and they began building their villages in more accessible areas, nearer their fields. Some began to build larger pithouses, rectangular in shape, with well-finished interiors. They built larger kivas near the centers of the villages. They developed new strains of hybrid corns, with larger ears and more nourishing kernels, now caching much of the surplus in large pots rather than in excavated storage pits. The women utilized new types of milling stones which reflected an increased reliance on agriculture. They began to experiment with more highly decorated pottery, producing new designs with red paint on brown clay backgrounds and, later, with red or black paint on white backgrounds. The men, having forsaken the spear and atlatl forever, produced more bows and arrows. The bands produced somewhat more jewelry, and they seem to have expanded trade, especially for shells from the Pacific Ocean. Their new ceramic designs suggest increased contacts with the Anasazi, their regional neighbors to the north.

Strangely, in some parts of the western Mogollon region, farming seems to have given way, at least partly, to resumption of hunting and gathering during the 6th and 7th centuries. In some sites of that time period, archaeologists have discovered, for example, that caches of wild plant seeds increased at the expense of farm crop grains. They don’t know whether the change is attributable to environmental conditions or nomadic hunter/gatherer invasions or some combination.

In the third phase of development, which began at about the end of the first millennium, archaeologists believe that the Mogollon experienced an intensification in Anasazi influence, perhaps as a result of either migrations or perhaps a cultural "budding" process. With stimulus from the north and an increase in population, the Mogollon people began to give up their traditional pithouse lodging, which had served them for a millennium. Like the Anasazi, they started to build communities of above-ground masonry structures, one- or two-story clusters of rooms, often with common walls. They built small hamlets with four to six rooms in a straight line or in a square. In a few instances, for example, the Grasshopper Ruin in Arizona, they built sizable pueblos with 500 or more rooms which faced an open plaza.

Near or within room clusters, they built small semisubterranean kivas, or family or clan "activity rooms," which apparently served not only as private or possibly clan "chapels," but also as kitchens and, conceivably, young bachelor sleeping quarters. These small kivas had central fire hearths, ventilator shafts, milling stones and, occasionally, apparent foot drums. The women kept a red clay jar placed beside the ventilator shafts and painted bowls set around the kiva floor.

In larger communities, the Mogollon constructed great kivas, or semisubterranean ceremonial chambers, most with rectangular floor plans, a few with circular floor plans, in the community plaza. Shamans increased their assortment of ritualistic icons such as painted stone effigies, symbolic disks and stone pipes in their medicine bags, suggesting an enriched spiritual life.

The new, above-ground, more populous Mogollon towns now cultivated larger fields, raised larger crops and constructed larger ditch-fed irrigation systems. They cached food, not in underground storage pits or large pots, but in masonry rooms with rock slab floors.

In a flowering of creativity, the Mogollon produced new forms of ceramics. Some painted new geometric designs and story-telling images on pottery surfaces. Between A. D. 900 and 1200, the Mogollon who lived in the Mimbres area in southwestern New Mexico produced black-on-white bowls which are now world-famous examples of the art of the prehistoric people of America.

They developed a more complex, urbanized and stratified society. Individuals evidently developed more specialized skills, turning from the generalized skills of earlier times. Some families apparently lived in larger apartment complexes, accumulated more wealth, owned more jewelry and held more power than other families.

Ironically, for reasons which archaeologists may never fully comprehend, the rise of Mogollon pueblo communities telegraphed the collapse of the culture. Archaeologists speculate that the calamity may have been attributable to drought, resource exhaustion, warfare, disease, religious system collapse, "greener pastures" or some combination. In any event, the western Mogollon peoples began abandoning their communities in several areas in southeastern Arizona and southwestern Mexico early in the 12th century. They had abandoned the Mimbres area by the 13th century. Some hung on until the early 15th century. Apparently many of them joined the western pueblos which existed into historic times, for instance, those of the Hopi and Zuni. About 1300, a mystery people, possibly from the Tucson and Phoenix areas, moved into several of the abandoned areas, and they built 100- to 200-room pueblos and at least one large kiva, but they, in turn, abandoned the area about 1500. The exact reasons for the abandonments and the destinations of the migrants remain a mystery in southwestern archaeology.

The Jornado Mogollon

To the east, the Jornado Mogollon also followed a development pattern of increased agriculture, pithouse village life, pueblo construction and, finally, cultural collapse, but there were several important differences. Compared with their western cousins, the Jornado Mogollon – often considered marginal in their development – appear to have relied less on agriculture and more on hunting and gathering. They followed a more nomadic life. They certainly left their characteristic brown pottery shards (fragments) widely scattered like prehistoric tin cans or Coca Cola bottles across their region. Even though they constructed pithouse hamlets near their fields, they may have occupied them only intermittently during the year, returning to them seasonally, for instance, when the time came to plant or harvest crops. They may not have developed hybrid corns with larger ears and more nutritious kernels. In their persistent nomadism, they appear to have established a more widespread trade network, bartering, for instance, with the western Mogollon, Texas High Plains tribes, Middle Rio Grande pueblos, and northern Chihuahuan communities. Some of the easternmost Jornado Mogollon bands appear to have hunted buffalo regularly along the western edge of the plains. They appear to have lagged by a century or more in constructing above-ground pueblos, often larger than those to the west and sometimes apparently fortified or positioned for defense. They may have experienced raids, possibly from Apachean peoples moving into the region. There is some evidence of violence and warfare. Even near large pueblos, they left only thin scatterings of trash, suggesting either brief or intermittent occupations.

As in the west, the Jornado Mogollon culture had collapsed by the beginning of the 15th century. Apparently, some bands headed north, possibly toward the Middle Rio Grande pueblos. Others may have headed south, toward settlements in Chihuahua. Others may have moved into the High Plains to follow the great buffalo herds. Still others may have remained behind, reverting to the basic nomadic hunting and gathering lifestyle which had never been far away. It seems possible that the Manso and Suma bands which greeted the first Spanish entradas into the northern Chihuahuan Desert could have been remnant descendants of the Jornado Mogollon.

More than any other desert Indians of the Formative Period, the Mogollon have left the most vivid graphic record of their religious beliefs. Images on stone and ceramic surfaces speak to a profound spirituality. That will be the subject of the next article in this series.

For additional reading, see the Smithsonian Institution’s Handbook of North American Indians, Southwest, Volume 9, "Prehistory: Mogollon," by Paul S. Martin; Archaeology of The Southwest, Second Edition, by Linda Cordell; Prehistoric New Mexico, Background for Survey, by David E. Stuart and Rory P. Gauthier; and Mogollon Variability, edited by Charlotte Benson and Steadman Upham. All these sources should be available in any university library. Linda Cordell’s book can be ordered through any book store if it is not available off the shelf.

"Paleo-Indians" (Part 1)

Desert Archaic peoples( Part 2)

Desert Archaic peoples - Spritual Quest (Part 3)

Native Americans - The Formative Period (Part 4)

Voices from the South (Part 5)

The Mogollon Basin and Range Region (Part 6) This page

The Mogollon - Their Magic (Part7)

Hohokam the Farmers (Part 8)

The Hohokam Signature (Part 9 )

The Anasazi (Part 10)

The Anasazi 2 (Part 11)

The Great Puebloan Abandonments (Part 12)

Paquime (Part 13)

When The Spanish Came (Part 14)

Life on the Margin (Part 15)

Life on the Margin (2) (Part 16)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 1 (Part 17)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 2 (Part 18)

The Outside Raiders (Part 19)

The Enduring Mysteries (Part 20)

Some Sites to Visit (Final Part)

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms