Cicadas

Genera Magicicada - Tibicen

by Jay W. Sharp

Cicadas – sometimes erroneously called “locusts,” which are actually certain grasshoppers – belong to the Homoptera, an order of insects distinguished by piercing and straw-like sucking mouthparts. Worldwide, cicadas comprise about 2000 species, which occur primarily in temperate and warmer regions. The cicada, although larger in size, counts spittlebugs, scales, planthoppers and the familiar aphids among its relatives.

Like all insects, the usually dark to brownish to greenish cicada has three body parts—the head, the thorax and an abdomen. It has six jointed legs, with the front pair adapted for digging—a reflection of its underground burrowing life when a nymph. A strong flyer, it has two sets of transparent and clearly veined wings, perhaps its most distinctive feature. At rest, it holds its wings like a peaked roof over its abdomen. It has bulging compound eyes, three glistening simple eyes and short bristly antenna.

The male cicada has on its abdomen two chambers covered with membranes – “tymbals” – that it vibrates, when at rest, to produce its “song.” It can make various sounds, including, for instance, an insistent call for a mate, an excited call to flight, or a hoped-for bluff of predators. It ranks as a loudmouth among the invertebrates and the noisiest of the insects. Both the male and female cicadas have auditory organs, which connect through a short tendon to membranes that receive sound. The male produces a call distinctive to his species. Ever faithful, the female responds only to the call of a male of her species.

Range and Habitat

The cicada holds residence across the Southwest, including the hot Mojave, Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts and the cold Great Basin Desert. It often makes its home in the plant communities along river bottoms and drainages, at elevations from sea level to some 5000 feet.

Life Cycle and Behavior

The cicada falls into one of two major groups, one called “dog day,” the other called “periodical.” The dog-day cicadas, which usually appear during the hottest days of summer, hence the name, include all of the several dozen species of the Southwest. They have a life cycle of two to five years. The better known include the Apache cicada, marked by a tan band around the back of its head, and the cactus dodger, noted for the male’s frenzied courtship behavior among the desert’s prickly pear and cholla cacti. The periodical cicadas, which include several species, all east of the Great Plains, have a life cycle of 13 or 17 years. Living longer than almost any other insect (a queen termite might live for 25 years or more), the periodical cicadas have gained worldwide fame.

Once one of our Southwestern female dog-day cicadas answers the call of one of our male cicadas and the two mate, she seeks out an inviting, tender twig or stem on a tree or a bush. She uses the jagged tip of her ovipositer (a spear-like egg-laying structure) at the end of her abdomen to gouge into the twig. She lays eggs, each shaped like a grain of rice, into the wound. She seeks out another twig and repeats the performance, eventually laying several hundred eggs.

Once a cicada nymph hatches, it drops to the ground, immediately burrowing into the soil, using its specially adapted front legs for the excavation. It seeks out a root and uses its specially adapted mouthparts to penetrate through the epidermis and suck out the sap. The cicada will spend all but the first moments and the last few weeks of its life as a nymph in its underground chambers. Once grown, it tunnels upward, to near the surface, where it constructs a “waiting chamber.” Upon receiving some mysterious signal, perhaps a temperature threshold, our nymph, along with its multiple kindred nymphs, emerges in a synchronized debut, one of the great pageants of the insect world. It climbs up nearby vegetation, molts for the final time, emerging from its old nymphal skin as a fully winged adult, beginning the celebration of the climax – and the coming end! – of its life.

After years sequestered in isolation in the pitch black of its underground chambers, the adult cicada rejoins the members of its species. It discovers the freedom of flight, the wonder of light and vision, the allure of sound and hearing, the promise of new generations. As during the nymph stage, the adult feasts on plants. It is a cause for a celebration of insects.

It is also a struggle for survival through its final days, for the cicada, nontoxic and relatively easily caught, especially during the final molt, must deal with a crowd of potential predators, including birds such as boat-tail grackles, various woodpeckers, robins, red-winged blackbirds and even ducks; mammals such as squirrels and smaller animals; reptiles such as snakes and turtles; spiders such as the golden silk spider; and other insects such as its especially fearsome arch enemy, the cicada killer wasp.

Should the male cicada, for example, find itself captured by the wasp, always a female, he can expect her to drive her stinger into his central nervous system, rendering him paralyzed. Transported in her grasp back to a cell in her burrow, he will become an unwilling but helpless host for a single egg and a living meal for her larva.

Of course, the cicada does have certain defenses. Once it has molted, it can fly swiftly to escape some potential predators. The raucous male alarm call may startle some predators, especially birds. It may occur in such numbers that it overwhelms the collective appetite of predators.

In perhaps its most novel defense, the desert cicada has developed an extraordinary ability to remain active throughout mid-day, when most would-be predators have to seek shelter from the desert heat. Notably, the cicada, unlike any other known insect, can sweat, which helps it dissipate heat. “When threatened with overheating,” said University of Arizona entomologist Robert L. Smith in an article called “Keepin’ Cool and Dodgin’ Spines,” “desert cicadas extract water from their blood and transport it through large ducts to the surface of the thorax, where it evaporates. The cooling that results permits a few desert cicada species to be active when temperatures are so high that their enemies are incapacitated by the heat. No other insects have been shown to have the ducts required for sweating.”

While the cicada may cause minor damage to the plants on which it feeds during its life cycle, it contributes in important ways to the environment. “For example,” said Douglas C. Allen in “The Cicadas,” posted on the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Internet site, “studies of the Apache cicada in Colorado River riparian communities revealed the ecological importance of this species. Feeding by the nymphs influences the vegetative structure of mixed stands of cottonwood and willow that occur in certain habitats. Excess water removed from the host’s water conducting tissues (the xylem) during feeding is eliminated as waste and improves moisture conditions in the upper layer of the soil. Xylem fluids are low in nutrients and the nymphs must consume large amounts of it to accommodate their energy needs. Most of the water is quickly excreted and becomes available to shallow rooted plants. Additionally, cicadas comprise an important prey species for birds and mammals, and the burrowing activity of nymphs facilitates water movement within the soil.”

The Cicada and the Human Species

The harmless cicada, which neither bites nor stings, has insinuated itself into the diet, medicine cabinets, folklore and mythology of the human species.

According to Allen, various Native Americans eat cicada, frying them in butter and eating them like popcorn. Based on information from informants, L. C. Wyman and F. L. Bailey said, in Navajo Indian Ethnoentomology, that Navajos ate cicadas “in ‘the old days,’ in their grandparents’ time, perhaps when food was scarce, but that children sometimes eat them now, that adults might eat them because ‘it is healthy' or ‘for protection for being strong.’ Usually the wings and the legs and sometimes the head were removed and the body roasted in hot ashes. Other methods mentioned were to burn off the wings and legs and salt the insects, to grind them with salt, to fry them, or to eat them raw. The taste was likened to peanuts, popcorn, or crackerjack; ‘it has its own sugar.’” Other references speak of the cicada as a source of human food across the Americas, Asia, the Congo and Australia.

If you would like to try a taste of cicadas, Maryann Mott offers a recipe in “Bugs as Food: Humans Bite Back,” National Geographic News Internet site: “Experts say that the best way to eat cicadas is to collect them in the middle of the night as they emerge from their burrows and before their skins harden. The bugs should be boiled for about one minute before being eaten. It is said they taste like asparagus or clam-flavored potato. Cicadas can be sautéed in butter with garlic and soy sauce for hors d’oeurves, or, incorporated into a stir-fry dish with vegetables as a main meal.”

As a medicine, the cicada has been ground into a powder that can supposedly be used to quieten crying babies, cure earache, reduce fever, prevent seizures, clear up rashes, stop tinnitus (ringing in the ears), induce sleep and treat battle wounds. As far as I know, however, cicada powder has not been approved by the FDA.

The cicada has entered the realm of folklore across much of the world, possibly because its periodic emergence from darkness into light and song has been equated with rebirth and good fortune.

According to the Earthlife Web Internet site, a Greek poet once wrote, “We call you happy, O Cicada, because after you have drunk a little dew in the treetops you sing like a queen.”

An Italian myth held that “one day there was born on the earth a beautiful, good and very talented woman whose singing was so wonderful it even enchanted the gods. When she died the world seemed so forlorn without the sweet sound of her singing that the gods allowed her to return to life every summer as the cicadas so that her singing could lift up the hearts of man and beast once again.”

Early English naturalist Thomas Moufet wrote that the cicada “eats nothing belonging to the earth and drinks only dew, proving cleanliness, purity and propriety; it will not accept wheat or rice, thus indicating its probity and honesty; - how appealing to celestial conservatives! It appears always at a fixed time, showing it is endowed with fidelity, sincerity and truthfulness.”

In our desert Southwest, the cicada outwitted the traditional trickster, the coyote, in Zuni mythology. It produced heat in Hopi mythology, heralding the arrival of summer, and it is “the patron of Hopi Flute societies in charge of both music and healing,” according to Stephen W. Hill, Kokopelli Ceremonies. The cicada played a key role as a scout and a conqueror in Navajo creation myths. It brought renewal and healing to other tribes.

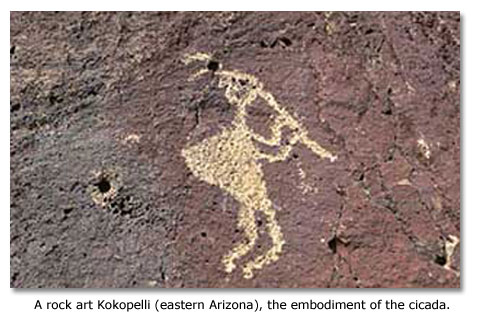

Across the Southwest, from prehistory into historic times, the cicada became identified with the hump-backed flute player, or Kokopelli, a charismatic and iconic figure portrayed in rock art and ceramic imagery.

“Kokopelli, the Cicada, is a musician,” said Gail E. Haley her children’s book Kokopelli, Drum in Belly. “His humpbacked silhouette is so appealing that his dancing figure has become almost the ambassador of the southwest—appearing on place mats, t-shirts, jewelry and metal works that can be found in tourist shops all over the world. I saw them in Australia, and now he can be found on bathroom towels, mats and toothbrush holders made in China.”

Kokopelli risked his life to lead the Ant People from mythological inner worlds to the present world, according to Haley, where they became The First People, after agreeing to follow the teaching of the Great Spirit.

“Kokopelli’s transparent wings have now unfolded and dried, and he is able to take to the sky. Kokopelli’s reward is flight. His continued gift to us is his reminder to be grateful that we no longer live in darkness.”

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms