Desert Varnish

Microscopic Organisms Color Desert Rocks

Text & Photos by Wayne P. Armstrong

Introduction

Rugged mountain peaks and sun-baked boulders throughout the arid Southwest are often colored in beautiful shades of orange, green, yellow and gray. At first glance the colorful coatings resemble a layer of paint, but close examination reveals that this unusual phenomenon is caused by a thin layer of microscopic organisms. The organisms include colonies of bacteria called "desert varnish," and colonies of symbiotic algae and fungi called lichens.

Desert varnish microbes generally survive better than lichens on the driest, sun-baked boulders. On boulders where lichens are established, the varnish bacteria do not survive as well. This may be related to a moisture difference or to organic acids produced by the lichens. These miniature rock dwellers have survived for countless centuries in some of the most seemingly inhospitable environments on earth and may represent some of the oldest living colonial life forms.

Ancient petroglyphs carved into desert varnish on Newspaper Rock, Utah.

Photo by Kelly Van Dellen.

Desert Varnish on Rocks & Boulders

One of the most remarkable biogeochemical phenomena in arid desert regions of the world is desert varnish. Although it may be only one hundredth of a millimeter in thickness, desert varnish often colors entire mountain ranges black or reddish brown.

Desert varnish is a thin coating (patina) of manganese, iron and clays on the surface of sun-baked boulders. According to Ronald I. Dorn and Theodore M. Oberlander (Science Volume 213, 1981), desert varnish is formed by colonies of microscopic bacteria living on the rock surface for thousands of years.

The bacteria absorb trace amounts of manganese and iron from the atmosphere and precipitate it as a black layer of manganese oxide or reddish iron oxide on the rock surfaces. This thin layer also includes cemented clay particles which help to shield the bacteria against desiccation, extreme heat and intense solar radiation.

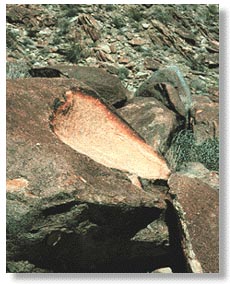

In the Anza-Borrego Desert of southern California, the sun-baked boulders are devoid of lichens. Instead, the rocks are coated with "desert varnish," a reddish layer of clay and iron oxide precipitated by remarkable bacteria. This large boulder has split apart revealing the lighter granodiorite beneath.

Several genera of bacteria are known to produce desert varnish, including Metallogenium and Pedomicrobium. They consist of minute spherical, rod-shaped or pear-shaped cells only 0.4 to 2 micrometers long, with peculiar cellular extensions. In fact, the individual cells are smaller than human red blood cells which are about 7.5 micrometers in diameter. Because of the radiating filaments from individual cells and colonies of some species, they are called appendaged bacteria.

All living systems require the vital energy molecule ATP (adenosine triphosphate) in order to function. In our cells ATP is constantly produced within microscopic bodies called mitochondria. As electrons flow along the membranes of our mitochondria, molecules of ATP are generated. The electrons come from the breakdown (oxidation) of glucose from our diet. Although varnish bacteria do not have mitochondria, they do have a similar inner membrane structure through which electrons flow to generate ATP.

Desert varnish on rock wall, Canyon de Chelly. Photo by Dennis Welker (Getty Images)

However, in varnish bacteria the electrons come from the oxidation of manganese and iron rather than glucose. Herein lies the marvelous adaptive advantage for producing a layer of black and red varnish on desert boulders. As you gaze at the miles of varnish-coated boulders and rocky outcrops throughout arid desert lands, you can appreciate the magnitude of these microscopic cells all producing their countless trillions of ATP molecules!

The sun-baked boulders of the Alabama Hills in Owens Valley, California look like they were blackened by ancient campfires. They are actually coated with a black layer of clay and manganese oxide precipitated by colonies of remarkable bacteria living on the rock surface for countless centuries.

Varnish bacteria thrive on smooth rock surfaces in arid climates. According to Ronald Dorn, perhaps 10,000 years are required for a complete varnish coating to form in the deserts of the southwestern United States. In fact, dating of varnished surfaces is of enormous importance to the study of desert landforms and to the study of early humans in America, since many artifacts lying on the ground become coated with desert varnish. Boulders of the Anza-Borrego Desert region are covered with a reddish-brown iron oxide, while boulders in parts of Owens Valley are blackened by a manganese oxide varnish.

The thin layer of reddish iron oxide varnish on this rock surface has been etched to reveal the lighter granodiorite beneath. Several Indian tribes utilized desert varnish to create their marvelous petroglyphs.

In the Alabama Hills near Lone Pine, the rocks are so black that they resemble basalt; however, if you scratch through the varnish layer, the light-colored granite is exposed. For thousands of years native Indians have used desert varnish for their rock carvings (called petroglyphs). Throughout northern Owens Valley, there are acres of elaborate petroglyphs carved into desert varnish and Bishop tuff, including spirals, circles, wavy lines, footprints, men, deer and desert bighorn sheep. It is fascinating to speculate on the origin and meaning of all these carvings.

This varnish-coated rock (with black layer of manganese oxide) in the Alabama Hills near Lone Pine, California has broken away revealing the lighter granitic core.

Some Good References About Desert Varnish & Lichens

1. Armstrong, W.P. and J.L. Platt. 1993. "The Marriage Between Algae and Fungi." Fremontia 22: 3-12.

2. Brock, T.M. and M.T. Madigan. 1988. Biology

of Microorganisms

(5th Edition). Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

3. Dorn, R.I. 1982. "Enigma of the Desert." Environment Southwest Number 497: 3-5.

4. Dorn, R.I. and T.M. Oberlander. 1982. "Rock Varnish." Progress In Physical Geography 6: 317-367.

5. Dorn, R.I. and T.M. Oberlander. 1981. "Microbial Origin of Desert Varnish." Science 213: 1245-1247.

6. Nash, T.H. 1996. Lichen Biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

7. Richardson, David H.S. 1974. The Vanishing Lichens. Hafner Press, New York.

Wayne P. Armstrong is Professor of Botany, Life Sciences Deptartment - Palomar College - San Marcos, California. He is publisher of WAYNE'S WORD®: A Newsletter of Natural History.

Related DesertUSA Pages

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms

Click here to see current desert temperatures!