Pueblo Rebellion

Conquest, Imperialism and Catholicism

Spain’s notions of conquest, imperialism and Catholicism – which lay like stratified bedrock beneath almost nine centuries of her history – defined her exploration and colonization of the lands of the Puebloan peoples. Her settlers, many considering themselves aristocrats, came by caravan, beginning in 1598. They rode horses descended from Spanish stock; carried cannon, harquebuses and swords from Europe; used rudely crafted two-wheeled ox-drawn wooden carts for conveyance; and drove great herds of livestock. As "European aristocrats," they felt culturally and morally superior to the Puebloans, and they presumed the right of entitlement to Puebloan stores, larders and labor. They intended to re-cast the Puebloan peoples into Spanish subjects. They expected the Puebloans to give allegiance to Spanish custom and law. Most of all, in their unshakable faith, they meant to convert the "heathen" Puebloans to Catholicism and to abolish the ancient religious beliefs.

Most Puebloans would come to view the Spanish, and especially their Franciscan friars in blue habits bound at the waist with ropes, as unwelcome intruders.

Conquest, Imperialism and Catholicism

Spain had mastered the art of conquest during the Reconquista, or Reconquest, the  epic seven and one-half century crusade to drive the Moorish sultans and their armies from the Iberian Peninsula. Led by Ferdinand and Isabella – known as the "Catholic Monarchs" – Spain celebrated her final triumph in January of 1492, when her forces marched into the streets of Granada, the last Moorish stronghold.

epic seven and one-half century crusade to drive the Moorish sultans and their armies from the Iberian Peninsula. Led by Ferdinand and Isabella – known as the "Catholic Monarchs" – Spain celebrated her final triumph in January of 1492, when her forces marched into the streets of Granada, the last Moorish stronghold.

Spain had perfected the craft of imperialism in the wake of the Reconquista, through systems called encomienda and repartimiento, royally approved grants which allowed an aristocratic new owner of re-conquered Iberian territory to tax the local peoples provided he would also Christianize, civilize and protect them. The aristocrat frequently collected his "taxes" in the form of spoils, tribute and enforced labor.

With the approach of victory over the Moors, Ferdinand and Isabella had sharpened the zeal of the Church into a fearful weapon – the Inquisition – to nationalize a fragmented land, convert or expel Moors and Jews, and assail the heretics. During the days of the Inquisition, Spain burned people at the stake for advocating the heresy of Protestantism, purportedly practicing the dark magic of witchcraft, carving their mutton in the kosher tradition, or for taking their weekly rest on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, rather on Sunday, the Christian day of worship.

The Spanish Empire

In the immediate aftermath of the Reconquista, Spain, intoxicated by a exaggerated sense of power and a fervor for Catholicism, laid claim to the most extensive empire in history, including many of the Caribbean Islands; much of the South American continent; all of Central America and Mexico; the lands along the northern Gulf of Mexico; the deserts of the southwestern North America; the islands of the Phillipines; large parts of Africa; all of the Iberian Peninsula; and large parts of the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. (Spain’s ambitions would transcend her national power and resources, leading to an unprecedented crash of empire, astonishing waste of treasure, and impoverishment of her people, but she left her enduring cultural and religious imprint across a vast region.)

Spain sent her conquistadores – the conquerors! – trained in the crucible of battle during the Reconquista, to the Western Hemisphere to plunder the Native American gold and silver treasures and to expand and consolidate Spanish domination. ("I came to get gold, not to till the soil like a peasant," declared Hernan Cortes, the conqueror of the Aztecs.) Spain sent her citizens to settle the land and subjugate the people. She dispatched her Franciscan and, later, her Jesuit friars to harvest the souls of the "heathens."

Spanish conquistadores, in their glittering armor, came to the lands of the Puebloans in an illusory search for treasure. Colonists – "aristocrats" – came with royal grants of land as well as the rights of encomienda and repartimiento to establish and consolidate empire. The missionaries came, financed by the Spanish royalty, to Christianize and civilize the Puebloans, making them loyal, if lower class, subjects under Spanish governance and anticipating Puebloan gratitude in return for holy salvation and a European value system.

The Puebloans viewed the invasion – the occupation of their lands and the demands for their housing, goods, food, labor and religious conversion – with smoldering resentment.

Colonists

"I take possession, once, twice, and thrice, and all the times I can and must, of the actual jurisdiction, civil as well as criminal, of the lands of the...Rio del Norte [the Rio Grande], without exception whatsoever, with all its meadows and pasture ground and passes," said Conquistador Don Juan de Onate, a wealthy Basque born in Mexico’s silver mining town of Zacatecas. It was April 30, 1598, the day Onate stood on the right bank of the river and ceremoniously claimed the land of the Puebloans on behalf of himself and his caravan of colonists, the first of the southwestern United States. "...this possession is to include all other lands, pueblos, cities, villas, of whatsoever nature now founded in the kingdom and province...and all the neighboring and adjoining lands thereto, with all its mountains, valleys, passes, and all its native Indians who are now included therein," said Onate, according to Gaspar Perez de Villagra who chronicled the expedition in his History of New Mexico, Alacla, 1610.

"I take all jurisdiction, civil as well as criminal, high as well as low, from the edge of the mountains to the stones and sand in the rivers, and the leaves of the trees."

Onate acted in the name of the "most holy Trinity, and of the eternal Unity, Deity, and Majesty, God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, three persons in the one and only true God…" and in the name of "the most Christian king, Don Philip, our lord, the defender and protector of the holy church, and its true son…"

"The work must be done," Onate believed, "because it is the will of God that all people [in this case, the Puebloan peoples] be saved. It is His divine will that His word be carried to all men, and that it be obeyed everywhere by everyone…

"There are other temporal reasons for which I should accomplish this conquest… That these peoples may be bettered in commerce and trade…gain better ideas of government…augment the number of their occupations and learn the arts, become tillers of the soil and keep livestock and cattle, and learn to live like rational beings…"

The Puebloan peoples knew utterly nothing, of course, of Onate’s ceremony hundreds of miles to their south, on the banks of the Rio Grande. Undoubtedly, they felt comfortable with their own religion, which had served them for centuries. They had commerce and trade networks, perfectly functional local governments, various occupations, craftsmen and artisans, farmers and domesticated turkeys. They probably even thought they lived like "rational beings."

Moreover, as Gaspar Perez de Villagra would remark, the Puebloan communities were "all well built with straight, well-squared walls. Their towns have no defined streets. Their houses are three, five, six and even seven stories high, with many windows and terraces. The men have as many wives as they can support. The men spin and weave and the women cook, build the houses, and keep them in repair. They dress in garments of cotton cloth, and the women wear beautiful shawls of many colors. They are quiet, peaceful people of good appearance and excellent physique, alert and intelligent…"

One suspects that the Puebloans may have been rather surprised to discover that they (including their souls) and their land (including the "leaves of the trees") now belonged to someone called "Philip," who was a person called a "king" from someplace called "Spain."

Onate, however, embodied the beliefs and attitudes of the Spanish military, colonists and Franciscan friars, who would extend their collective reach into every corner of Puebloan life in the coming decades.

New Rule

The Puebloans soon learned that the Spanish colonists came, not only as imperialistic conquerors filled with religious self-righteousness, but also as self-proclaimed aristocrats averse to "peasant" labor such as tilling the soil. As Marc Simmons said in his "History of Pueblo-Spanish Relations to 1821," Handbook of North American Indians, Southwest, Volume 9, the Puebloans saw the new settlers become increasingly oppressive and demanding over time, especially after the failure to find treasuries filled with gold and silver or deposits rich in valuable minerals. The Indians watched in anguish as Spanish soldiers commandeered winter stores of food and stripped blankets from women and children.

The Puebloans discovered almost immediately that their individual communities lacked the power to contest Spanish armaments. Acoma, the spectacular mesa-top pueblo in west-central New Mexico, ambushed a party of Onate’s soldiers in December of 1598, killing several men. Within weeks, Acoma suffered savage reprisal by 70 Spanish soldiers, who were schooled in the traditions of the Reconquista and armed with cannon, harquebuses and swords. According to Robert Silverberg in The Pueblo Revolt, 1000 Acomans lost their lives in the battle, which lasted for three days. Five hundred found themselves bound into Spanish enslavement. All surviving men over 25 lost a foot to Spanish blades as punishment. The pueblo lay in ruins. The Acomans killed only two Spaniards in the fight. Another pueblo, Quarai, in central New Mexico, attacked Spanish soldiers taking salt from a nearby dry lake bed, killing two, in the early summer of 1601. Like Acoma, Quarai suffered swift and brutal retaliation in a battle which lasted for five days. According to Silverberg, 900 Indians died, 200 fell captive. Their pueblo went up in flames. The Quarai warriors did manage to wound 40 Spaniards.

Confronted by the thunder of harquebuses and cannons, the Puebloans became relegated, humiliatingly, in their own land, to second class citizenship, in effect, serfs, often subject to brutal abuse. Drafted into virtual slave labor, said Simmons, Indian workers were forced to cultivate the fields of colonial land owners, tend the haciendas of Spanish aristocrats, construct new buildings for government officials, and weave blankets and clothing for the settlers’ women and children—at the cost of neglecting of Puebloan fields, homes, communities, crafts and family needs. As demanded by colonial administrators, each pueblo was forced to elect a slate of government officials – other than their traditional leaders – every year to deal with the Spanish government at Santa Fe. According to Pueblo Indian Joe S. Sando’s Pueblo Profiles: Cultural Identity Through Centuries of Change, Puebloan women knew the anguish of rape by Spanish soldiers. Puebloan warriors swung from Spanish ropes or disappeared into slavery for merely talking to Apaches and Navajos, enemies of the colonists. Other Puebloan warriors suffered public whippings or imprisonment as an Inquisition-style punishment for suspected witchcraft.

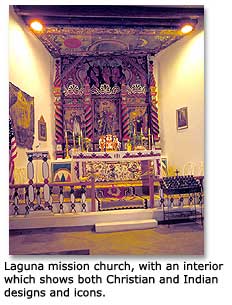

If the Puebloans felt threatened by Spanish firepower and humiliated by Spanish colonial demands, many – especially the traditionalists – felt enraged by the missionary friars’ move to introduce Catholicism and abolish ancient religious beliefs. "As harsh and humiliating as the systems of forced work and payment were," said Sando, "the continual religious persecution during the years from about 1598 to 1680 was even more galling to the Indian people..." Driven by the priests, Puebloan communities built ostentatious mission churches. They farmed land and raised livestock for the profit of priests, according to Simmons. They saw their own traditional ceremonial chambers – kivas – filled with sand or torched; their sacred masks, prayer sticks, emblems and images confiscated and burned; and their most important religious ceremonies banned at the hands of the clergy, said Silverberg. The Puebloans regarded these acts as sacrilege; the friars regarded them as God’s mandate. The Indians endured the indignation of having a priest shear their hair for minor offenses. In 1655, the Hopis, said Simmons, reported that one of their friars had first whipped an Indian and then burned him alive for practicing idolatry. A few years later, the Taos Pueblo reported that a friar had bludgeoned to death a woman who had not followed his directions to spin cotton.

The Puebloan misery deepened and the death rate climbed through the decades with periodic drought, famine, lethal European diseases and intensifying Apache and Navajo raiding. "The harmony of their lives had been seriously threatened," said Sando. "When their indigenous religion had been suppressed, it means that the natural order of life was disrupted." According to Simmons, "Lack of rain in 1640 combined with the destructive Apache raid of that year produced widespread famine and 3000 Indian fatalities... Other thousands perished in the drought and famine of 1663-1669..." In the midst of crises, the Puebloans watched, bewildered, as the Spanish settlers and clergy clashed over who had the predominant rights to exploit the Indians.

If conquest, imperialism, persecution, nature and conflict seemed to conspire against the Puebloans, some of them nevertheless found something promising and meaningful in a new way of life, especially early in the Spanish colonial period. As Silverberg said, they saw and admired the courage and resilience of the friars who came alone to their pueblos to teach Catholicism. Storytellers themselves, they responded to the Christian stories of creation, Adam and Eve, and Jesus’ birth and crucifixion. They warmed to Franciscan expressions of gentleness and caring, the themes set by St. Francis, the founder of the order. They took satisfaction in learning from the friars the Spanish farming methods, animal husbandry, building techniques, music, painting and sculpture. They took pride in their construction of their charming mission churches. Even as they retained their traditional beliefs and ceremonies, often in the secrecy of their kivas, many submitted to baptism and turned to Christian values and beliefs.

As the decades passed, however, the relentless threat of military force, the conscription of food and clothing, the enforced work in Spanish homes and fields, the inevitable neglect of their own homes and fields, the assault on traditional beliefs, and the suffering from drought and disease virtually overwhelmed the work of any well-intentioned Franciscan friars.

Prelude to Revolt

Puebloan protest had erupted intermittently for years. For instance, the Zuni, said Simmons, killed two friars in 1632. The Hopis killed a friar the following year, according to Silverberg. A Rio Grande pueblo revolted, unsuccessfully, around 1645 after the Spanish hung 40 Indians who refused to convert to Christianity. More Rio Grande pueblos revolted, unsuccessfully, in 1650, and 29 more Indians swung from Spanish ropes.

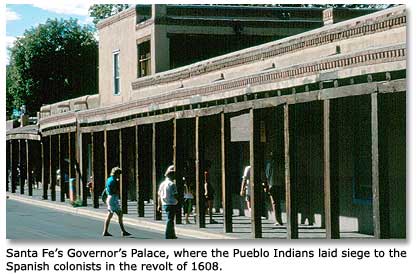

Believing that Christianity had failed them, Puebloans followed their religious leaders in a campaign to rejuvenate traditional beliefs and ceremonies, particularly in the Rio Grande villages. In 1675, 47 of the leaders were arrested by Spanish cavalry in their villages and tried and convicted for "witchcraft" and "idolatry" before the courts in Santa Fe. Four hung from ropes in the plaza in front of the Governor’s Palace, the Spanish seat of administration, and 43 felt the lash of Spanish whips and the humiliation of Spanish jails. They remained imprisoned for weeks, until a delegation from several pueblos won their release after a vague but apparently frightening threat of massive and unified retaliation against the Spanish.

In their distress, traditionalist leaders of pueblos within easy reach of Santa Fe – the core of the Spanish repression – began to meet in secret to address what Sando said was a "galling problem… How long were they to put up with the persecution and exploitation they suffered? The consensus was that something had to be done. But what? The situation of the tribes was grave."

Over the months, a leader began to emerge, a medicine man named Pope, one of the 43 flogged and imprisoned by the Spanish in Santa Fe. "…it was said," according to Sando, "that Pope was not arrogant but instead was always willing to learn, consider advice, and to explain his decisions." A Tewa-speaking Puebloan born in the village of San Juan, Pope was, said Silverberg, "consumed by hatred, possessed by a vision of his land restored to its old way of life, hungering for vengeance against those who had bruised his body and oppressed his spirit…"

In months of secret meetings centered at the Taos Pueblo, 70 miles north of Santa Fe, Pope, supported by other leaders, drew on sorcery, magic and negotiation to develop a well crafted strategy to drive the Spanish from the Puebloan lands. First, they welded nearly all the proudly independent pueblos, including the Zuni and the Hopis, into a unified force with the common purpose of acting against the Spaniards. Next, the allied pueblos all agreed to strike on the same day in August of 1680. They assigned runners to act as messengers. The pueblo leaders would mark the passage of the days with strands of knotted leather, each untying one knot each day until they reached the final one in the series. Then they would strike. Rumors and uneasiness began filtering through the Spanish communities. Tensions rose like a gathering storm.

Revolt

The pueblos untied the last knots in their strands of leather on August 10, 1680, and according to Silverberg, 17,000 thousand Puebloans, including 6000 warriors painted in their colors of battle, rose up in vengeance against 2500 to 3000 colonists, an overwhelming challenge to traditions cast in nine centuries of Spanish history.

They struck the mission churches in the pueblos within the upper Rio Grande drainage basin, killing 22 of 33 friars and demolishing and burning holy icons and interiors. Warrior bands rampaged across the river valleys and mountain slopes, attacking isolated farms and haciendas, killing entire families, wiping out entire community populations. To the west, the Hopis killed friars and Spanish soldiers and wrecked mission churches. The Zunis killed a friar. Acoma killed its friar, taking its revenge and reclaiming its independence after the disaster in the fight with the Spanish in January of 1599.

The Puebloans watched survivors flee to Santa Fe in search of refuge, then 500 or more warriors, armed with captured Spanish weaponry, laid siege to the capitol on August 12, 1680. Negotiations failed. The warriors attacked Santa Fe. Their force grew to some 2500. They drove the colonists into the Governor’s Palace, beside the plaza where Spanish whips had flayed the backs of the 43 Puebloan medicine men some five years earlier. Over five days, the warriors inflicted heavy casualties, burned a nearby church and surrounding buildings, cut the water supply, and mockingly sang the Catholic liturgy.

Finally, on August 18, the warriors lifted their siege in the wake of a desperate Spanish counterattack, which cost the Indian force more than 300 men. Bands of warriors watched from the hills as the Spanish began a fearful exodus to the south, down the Rio Grande through a tableau of devastation and death, on August 21. Believing they had regained their freedom and their right to their traditions, they watched the mournful column disappear, leaving some 400 dead in the ruins of mission churches, farm homes, haciendas and villages.

The Spanish, however, had already begun to plan their return to New Mexico. They remembered the Reconquista of Spain after seven and a half centuries, the march into Granada in 1492, the glory of the conquest over the Moors. They had already begun to speak of the Reconquista of the land of the pueblos, a march into Santa Fe in the coming years, and the glory of a conquest over the Puebloan peoples.

by Jay Sharp

![]()

Desert People and Cultures Index

When The Spanish Came

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms