Socorro Mission Texas

Preservation Project

Our desert basins and mountain ranges hold a national treasure trove of prehistoric and historic settlements, missions, forts, haciendas, farmsteads and other structures. They stand as monuments to the cultural blend of Native Americans, Hispanics and Anglos, who defined the American Southwest, making it a larger-than-life story of tradition, legend and myth. |

On December 7, 2005, Reverend Armando X. Ochoa, D. D., the Bishop of El Paso, presided over a special mass to celebrate the prodigious five-year preservation of the Socorro Mission, Nuestra Señora de la Limpia Concepción de los Piros de Socorro del Sur, also locally known, affectionately, as La Purísima, the Most Pure. Several hundred attendees participated in the much-anticipated event. Future generations will cherish the newly restored landmark.

Mission History

The Socorro Mission is located southeast of a traditional ford on the Río Grande, on the branch of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (Royal Road to the Interior) that runs through westernmost Texas, from San Elizario to downtown El Paso. The mission arose in the aftermath of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, when the Indians drove the Spanish from the settlements, haciendas and missions in northern New Mexico. Built at the community founded by Spanish refugees and their Piro allies, the first permanent Socorro Mission church building was dedicated by 1692, at a location a mile south of the current building. Ravaging floodwaters swept the first church away in 1740. Another flood destroyed its successor in 1829.

Given the current control and containment that we are accustomed to today, it is difficult to comprehend what a raging river the Río Grande could be. Early accounts describe the historic floodwaters cresting far upstream of Socorro, and scouring everything in its path as it surged southward. The Socorro Mission arose as a testament to the strength and resiliency of those who persevered despite hardships.

The present building, the mission’s third permanent structure, was formally dedicated in 1843. The walls are more than five feet thick at the base. The main nave measures 22 by 100 feet. The ceiling measures 26 feet high. The nave features interior roof supports (decorated corbels and vigas, which, archaeological evidence suggests, were salvaged from the late-17th and early-18th century mission buildings. Tradition holds that the original Piro settlers painted the corbels and vigas. Although the centuries-old designs have lost much of their brilliant tint, the painstaking and intricate workmanship remains evident. A workshop to learn more about the plant-based pigments is planned. The unique stepped parapet at the front façade, and other distinctive alterations over the intervening 162 years, have resulted in the monumental edifice that remains at the heart of the Socorro, Texas, community today.

The Socorro Mission is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (1972). It is a recorded Texas Historic Landmark (1963). It is commemorated by a Centennial Marker (1936) and two Texas Historical Commission Markers (1983). The Office of the Texas Historical Commission State Archaeologist identifies the entire complex as Site No. 41EP38. Several years ago, the Socorro Mission Preservation Project was selected to receive a coveted State of Texas “Preservation Excellence” Award.

Causes of Deterioration

Simple reasons account for failures in adobe buildings. Since the adobe bricks are set directly on the ground (many historic structures have no foundation), capillary action wicks soil moisture into the walls. Traditional mud and lime plasters at the Socorro Mission allowed the adobe walls to endure natural wet and dry cycles for more than 150 years. During the 1920s, and perhaps earlier, the application of impermeable cement-based products around the walls caused moisture entrapment. Penetrating moisture could no longer evaporate. By the 1990s, several areas within this nationally significant church faced imminent collapse. Undersized window and door lintels, inadequate site drainage, the removal of interior structural and architectural braces, deteriorated mortar joints, and a lack of adequate routine maintenance contributed to the building’s precarious condition.

La Purísima Restoration Committee

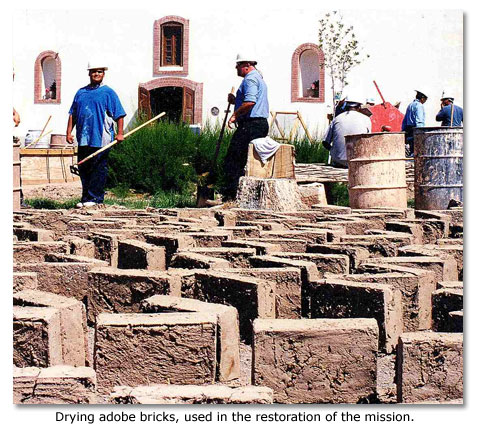

In 1998, the non-profit Cornerstones Community Partnerships, Santa Fe, New Mexico, was invited by La Purísima Restoration Committee (Tury Morales, Chair) to conduct a preliminary “Conditions Assessment” of the mission building. In the summer of 2001, after two years of fundraising, a full-time crew began the hands-on work. An extraordinary output of effort and teamwork replaced the concrete “collar” at the base of the church walls with adobe, repaired deteriorated portions of the walls and roof parapet, stabilized the bell tower and façade, and re-plastered the interior with “yeso,” or gypsum. Once the exterior cement stucco was removed, thousands of pumice stones were inserted into the adobe head joints to serve as a natural anchoring system for the lime plaster. Between seven and 10 coats of lime wash have been applied to the finish coat of lime plaster. Approximately 30 percent of the existing corbels and vigas were consolidated and repaired using fiberglass dowels and epoxies. The nave features a new stone floor. The roof has been repaired, and the clerestory feature replaced. Field staff and volunteers made approximately 22,000 new sun-dried bricks to replace deteriorated adobe throughout the structure. The entire building has now been conserved, top to bottom, inside and out. With minimal routine maintenance, Socorro’s cherished Mission should last for many generations.

Archaeological and Architectural Investigations

A significant amount of new archaeological, historical and architectural evidence was collected throughout the project, in collaboration with the Sociology Anthropology Department of the University of Texas at El Paso and volunteers with the El Paso Archaeological Society. Thousands of homemade wooden matches, pottery sherds, Mexican centavos, a buffalo head nickel, a Mercury head dime, tiny Milagros and small toys are among the many artifacts collected. The project coordinators are seeking funding to permanently display the artifacts inside the mission.

Support from the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) enabled Jacobo Herdoiza, an Ecuadorian architect and ICOMOS intern, to prepare a series of unprecedented architectural drawings based on research compiled by Jesuit archivist Ernest J. Burrus. The project also hosted ICOMOS interns from South Africa, Ghana, Mexico, and Australia. A North American Community Service initiative furnished energetic interns from Canada, Mexico and the United States.

Diverse Workforce

Throughout the process, project coordinators and crew members successfully supervised workers from a wide diversity of groups, including “Welfare-to-Work” adult trainees, clients with the felony and juvenile court systems, and students from the nearby K. E. Y. S. Academy. Principle volunteer groups include: the Upper Rio Grande/Texas Workforce Commission; Judge Ruben Lujan’s Juvenile Court System (Clint, Texas); felony West Texas Community Supervision and Corrections Department; Texas Department of Family and Protective Services; Lee and Beulah Moore Children’s Home; Schaeffer Halfway House; the Center for Civic Engagement (University of Texas at El Paso); the Southwest Key program; Socorro High and other local high school students, and journeymen electricians from the El Paso Community College Advanced Technical Center.

Key Partnerships

Collaboration among additional organizations – including Native American, Hispanic and Mexican – is credited with the success of the preservation effort. Generous individual, private, corporate and public benefactors donated the necessary funding and in-kind services, amounting to just under $2 million.

Cornerstones Community Partnerships’ partners in the restoration included the Catholic Diocese of El Paso; Historic Missions Restoration, Inc, El Paso; the United Nations of Native Americans; the National Trust for Historic Preservation; the El Paso Archaeological Society; the North American Community Service; the International Council on Monuments and Sites; the Engineering Technology Department at New Mexico State University; the Parish of La Purísima; the City of Socorro; the Socorro Independent School District; the El Paso Community Foundation; the University of Texas at El Paso; the El Paso Mission Trails Association; the Mission Valley Chamber of Commerce; La Purísima Restoration Committee; and the Texas Historical Commission. Active support on our Volunteer Days was provided by a wide variety of individuals and organizations, including Girl Scout Troop #325, the Montwood High School Campus Crimestoppers Club, Socorro High School students, the El Paso Junior History Club and numerous other church, school and social organizations. The Houston Endowment provided core financial support. State Senator Eliot Shapleigh, U. S. Congressman Sylvestre Reyes, and U. S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison were instrumental in helping to secure a critical Save America’s Treasures appropriation—the federal “bricks and mortar” preservation program administered by the National Park Service.

Accomplishments

In addition to saving a national treasure from collapse, the community-rooted project to conserve the historic Socorro Mission integrates historic preservation with at-risk youths apprenticeships, on-the-job adult training, the promotion of cross-border collaborations and economic development through heritage tourism. The project also helped alleviate chronic local unemployment. Valuable skills, both tangible (carpentry, adobe making, brick laying, plastering, etc.) and intangible (sense of pride, teamwork, strong work ethic and an understanding of patri

monio) have been instilled. Community apathy was counteracted. Social alternatives were presented to area youths, including those at-risk for involvement in substance abuse, truancy and gang violence. Hopefully, the project to conserve Socorro Mission will be used as a model for other community revitalization projects. It is clear that historic preservation can be used as a powerful means to promote social activism.

Special Thanks

The following individuals would like to express heartfelt gratitude to the dozens of persons who served on the preservation crews, and to the hundreds of volunteers who helped them:

- Donna Vogel, Executive Director, Cornerstones Community Partnerships

- Pat Taylor, Project Coordinator, Cornerstones Community Partnerships

- Jean Fulton, Assistant Project Coordinator, Cornerstones Community Partnerships

- Tury Morales, Chair, La Purísima Restoration Committee

- Most Reverend Bishop Armando X. Ochoa, President, Historic Missions Restoration, Inc.

- Frank Gorman, Vice-President, Historic Missions Restoration, Inc.

Special thanks also to those who provided financial support, and to all who have donated their professional expertise and services.

Visit the Mission

The Socorro Mission is located 20 minutes southeast of downtown El Paso. To visit the mission, you can take the Paisano exit off of I-10 South. Follow Paisano Road (Route 85) into downtown El Paso. Turn right (west) onto Santa Fe Street, which curves underneath the pedestrian bridge to Juarez, Mexico, and turns into Border Highway, or Loop 375. Take the Socorro/Alameda exit off of Border Highway, and take the first right onto Socorro Road. Take a left at the light on Winn Road and look for the back of Socorro Mission on your right.

CORNERSTONES COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPSSince 1986, the non-profit Cornerstones Community Partnerships (Santa Fe, New Mexico) has worked to preserve historic architecture throughout New Mexico and the Southwest. Cornerstones has built an international reputation for the creative use of historic preservation as a tool for community revitalization, and as a method for engaging all ages in the conservation of traditional building skills and cultural traditions. The Cornerstones staff has participated in more than 300 community-based preservation projects, each involving the use of traditional materials and techniques. Project sites include those in Pajarito, La Cueva, Upper Rociada, Doña Ana, Zuni Pueblo and Chacon. Current work sites include St. Augustine’s Church at Isleta Pueblo (New Mexico), Acoma Pueblo (New Mexico), and the historic Hubbell House (New Mexico). For more information please visit the Cornerstones web site. |

Written by Jean Fulton, The Southern Region Program Coordinator, Cornerstones Community Partnerships (Santa Fe, NM)

Hotels/motels

There are hotels/motels in El Paso with something for every taste and price range. For a complete list and to check availability or make reservation on line Click Here.

Camping & RV Parks

There are numerous camping and RV accommodations in and around El Paso. For more information, contact:

- El Paso Convention and Visitors Bureau

One Civic Center Plaza, El Paso, TX 79901-1187

915-534-0696 fax 915-532-0263

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms

SEARCH THIS SITE

The Mountain

Lion Video

The Mountain Lion, also known as the Cougar, Panther or Puma, is the most widely

distributed cat in the Americas. It is unspotted -- tawny-colored above overlaid

with buff below. It has a small head and small, rounded, black-tipped ears. Watch

one in this video.

View Video about The Black Widow Spider. The female black widow spider is the most venomous spider in North America, but it seldom causes death to humans, because it only injects a very small amount of poison when it bites. Click here to view video.

View Video about The Black Widow Spider. The female black widow spider is the most venomous spider in North America, but it seldom causes death to humans, because it only injects a very small amount of poison when it bites. Click here to view video.

The Rattlesnake Video

Rattlesnakes come in 16 distinct varieties. There are numerous subspecies and color variations, but they are all positively identified by the jointed rattles on the tail. Take a look at a few of them, and listen to their rattle!

___________________________________

Take a look at our Animals index page to find information about all kinds of birds, snakes, mammals, spiders and more!

Click here to see current desert temperatures!