Life on the Margin

The Mogollon, The Hohokam and The Anasazi

By the beginning of the second millennium, the three major Puebloan traditions – the Mogollon, the Hohokam and the Anasazi – had arisen in the southwestern deserts of North America. Within a few centuries, those traditions contracted and consolidated. Simultaneously, a fourth major Puebloan tradition – Casas Grandes, or Paquime – emerged in Mexico’s northwestern Chihuahua. By about the middle of the 15th century, it had collapsed. Its people dispersed. While the great Puebloan traditions rose and fell and sometimes reconstituted themselves, numerous other tribes lived along the geographic and cultural margins.

The River and Delta Yumans

From about A. D. 700 to 1550, the River and Delta Yuman people – often called the Patayan – occupied the western sector of the Sonoran Desert, that fearsomely hot and dry region where the Colorado River divides western Arizona from southeastern California and southern Nevada. The geography comprises wide and sandy valleys and small, stark mountain ranges. The 1000-square-mile primal landscape called the Pinacate volcanic field, on the border between southwestern Arizona and Mexico’s northwestern Sonora, punctuates the harshness of the land. Summer daytime air temperatures soar to more than 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Soil surface temperatures approach 180 degrees Fahrenheit. Annual rainfall averages less than three inches. Rainfall fails completely in some areas during the driest years. Drought-tolerant plants such as creosote, white bursage and a few cacti and shrubs grow in widely dispersed stands. In contrast to the surrounding desert, the Colorado River (like Egypt’s Nile River) once inundated its flood plains annually, leaving behind fertile deposits of silt.

The Patayan, who lived in small, highly mobile and loose-knit bands, left a confusing and ephemeral archaeological record. They likely wound some threads from the Mogollon, Hohokam and Anasazi traditions into their cultural skein. They raised corn, beans and squash in the river’s silt deposits, depending on the annual inundation rather than irrigation to nourish their crops. More than their cultural kin, they continued to rely heavily on the ancient traditions of hunting wild game and gathering wild plants (especially mesquite beans) to supplement their agricultural production. They moved frequently in response to the seasons of inundation, planting, harvesting and hunting, often seeing the flood plain campsites of one year swamped by the river during the following year. They lived in temporary hamlets, or "rancherias," which comprise settlements of widely separated lodges. "Rectangular earth lodges with lateral entryways, masonry surface structures with small rectangular rooms, and deep pithouses lined with timber all were reported," Linda Cordell says in Archaeology of the Southwest. The Patayan people stored and protected food in sealed vessels, pounded their grains to flour in mortars and pestles, and cooked in stone-lined roasting pits. They fashioned their ceramics with paddles and anvils, producing undecorated pieces in the early centuries and red-painted wares in the later centuries.

Presumably it was the Patayan who produced the astonishing "intaglios," or "geoglyphs" – monumental landscape art consisting of images such as human figures, mountain lions and geometric shapes – which occur along the river basin from Blythe, California, and Ehrenberg, Arizona, upstream to southern Nevada. In creating an intaglio, the Patayan landscape artists used the surface of the earth itself as a canvas. They scraped away a thin blanket of dark soil to reveal an underlying layer of lighter soil, and they shaped the scraping into a form which typically measured more than 30 feet in length. They produced at least one which measured nearly 300 feet. These are now the most famous such figures in North America.

The Patayan contributed genes and cultural traditions to the rise of the historic Yuma – or, Quechan – and Mojave peoples, who occupied the lower Colorado River basin when the Spanish arrived in 1602. Like their ancestors, the Quechan and Mojave Indians farmed the river’s silt deposits, raising corn, beans, squash and other crops. They hunted wild game. They hooked or trapped fish. They harvested wild plants, especially mesquite beans. They lived in settlements of several hundred people, who occupied dome-shaped brush huts. Warlike, the Quechan and Mojave peoples fought for territory, trade routes, captives and spiritual fulfillment. Late in the 20th century, about 2500 Quechan people lived on the Fort Yuma-Quechan Reservation, which lies along both sides of the Colorado River immediately north of Yuma, Arizona. Descendents of the Mojave people lived on the Colorado River Indian Reservation, which straddles the stream north of Blythe, and on the Fort Mohave Indian Reservation, which extends into Arizona, California and Nevada near Needles.

The Upland Yumans

The Upland Yumans occupied a range which extended from the Grand Canyon and its deeply dissected tributaries in the western Colorado Plateau, to the Colorado River basin in the eastern Mojave Desert. Weather at the higher elevations ranges from moderate in the summer to severe and snowy in the winter, with about 15 inches of precipitation falling in an average year. Summer daytime air temperatures on the floor of Grand Canyon often exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit, with only about eight inches of rainfall in an average year. Weather in the river basin downstream from Grand Canyon varies from hot and windy in the summer to mild in the winter, with annual precipitation averaging five to seven inches and falling mostly in January through March. Ponderosa and pinyon/juniper forests grow at the higher elevations of the Colorado Plateau, and rolling grasslands and desert scrub and yuccas dominate in the desert basin.

To an even greater extent than the River and Delta Yumans, the Upland Yumans relied on hunting game, including deer, bighorn sheep and smaller animals, and on gathering wild plants, especially yucca. Some raised corn, beans and squash in garden plots beside canyon streams during the summer then killed game and harvested wild food plants on the canyon rims during the other seasons. According to Kenneth M. Stewart in his paper, "Yumans: Introduction," in Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest, Volume 10, "The Upland Yumans lived in dome-shaped shelters thatched with grass, they dressed in buckskin, and they wove basketry as their principal craft."

The Upland Yumans comprised several sub-groups, including: the Havasupai ("those of the blue-green water"), who raised irrigated garden crops in Havasu Canyon, a tributary to Grand Canyon, in the summer and hunted and gathered in the plateaus during the fall, winter and spring; the Hualapai ("those of the tall pines"), who planted small occasional gardens and hunted game animals and gathered wild plants in the arid region to the south and west of the Havasupai; and the Yavapai, who – like their Archaic predecessors thousands of years earlier – relied primarily on hunting and gathering in the region south of the Havasupai and the Hualapai. Today, the Havasupai and Hualapai live on reservations within their ancestral ranges, along the south rim of Grand Canyon. The Yavapai live on reservations within or immediately south of their original range.

The Sinagua

Between the 6th and the 15th centuries, the Sinagua people, who probably emerged from Yuman origins, occupied the region which encompasses the ponderosa and pinyon/juniper forests and the grasslands and desert scrub country from the vicinity of Arizona’s Sunset Crater volcano southwestward to the state’s Verde River. They practiced a rudimentary flood plain agriculture in the early centuries, irrigating their farm plots with systems of check dams and irrigation ditches. They supplemented their crops with hunting and gathering. They lived in hamlets of lodges which evolved over time from circular pithouses to "sub-square pithouses with lateral entries or antechambers, teepee-like structures, masonry-lined pithouses, and small masonry surface structures," according to Cordell. "Overly large circular pithouses may have been associated with intercommunity ceremonial activities."

The Sinagua who occupied the northeastern part of their range experienced a cataclysmic interruption of their lives between 1064 and 1067, when the Sunset Crater erupted repeatedly, blanketing some 800 square miles of land with lava, cinder and ash. Although Sunset Crater continued to erupt intermittently for two more centuries, the Sinagua began to move back into the region within a matter of years, capitalizing on a period of increased rainfall and, possibly, the mulching effects of the ash falls. As they established new pithouse and pueblo villages, the Sinagua – more than either the River and Delta or the Upland Yuman groups – expanded their sphere of interaction with both near and distant peoples, especially the Mogollon, Hohokam, Anasazi, Patayan and, possibly, even the Mesoamericans.

During the 12th century, the Sinagua of the Sunset Crater region appear to have evolved, in many respects, into a synthesis of traditions. For example, they reflected relationships with the Mogollon in pithouse architecture and ceramic styles; the Hohokam in crafts and Mesoamerican-style ball court construction; the Anasazi in pueblo masonry and ceremonial chamber, or kiva, construction; and the River and Delta Yumans in projectile point styles. Directly or indirectly, they acquired parrots, copper bells and mythology from Mesoamerica. Like the Zuni and Hopi, the Sinagua likely established clans, and they seem to have adapted several different religious beliefs, which we see expressed through their burial customs, including cremations and flexed and extended inhumations.

Like some Puebloan neighbors, the Sinagua developed an organized and stratified social system. According to National Forest archaeologist Piter Pilles (writing in Ekkehart Malotki’s and Michael Lomatuway’ma’s Earth Fire), the Sinagua built upscale villages at prominent locations, incorporating prestige architectural features such as community ceremonial chambers, courtyards and ball courts. They buried high status individuals, for instance, the well-known "Magician" at the Sinaguan site called "Ridge Ruin," with elaborate grave offerings such as ceramics, wands, baskets and jewelry.

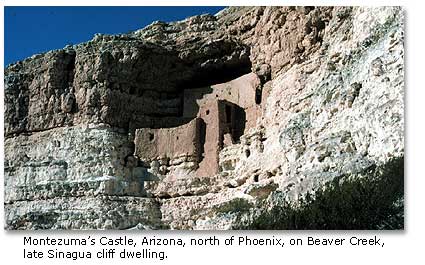

In the 13th century, the Sunset Crater Sinagua began to abandon their region, probably because annual average rainfall diminished. Some moved to the southwestern part of their range. In the 14th and 15th centuries, they built cliff dwellings, including the famous five-story, 20-room Montezuma’s Castle (which had no association with either the Aztec emperor Montezuma nor with any castle) in a towering limestone balcony overlooking Beaver Creek. Others, said Pilles, "probably moved east to the Zuni area and the Rio Grande Valley, while the majority moved through the Hopi Buttes area before arriving at the Hopi Mesas?" The Sinagua migrations seem to be incorporated in Hopi oral histories. The Sinagua culture as a distinct entity disappeared from the archaeological record after the 15th century.

The Salado

The Salado people, who occupied central Arizona’s Tonto Basin region from about 1200 to 1450, were "no one and everyone," Jefferson Reid and Stephanie Whittlesey said in The Archaeology of Ancient Arizona. Perhaps more than any other prehistoric population in the deserts of the American Southwest, the Salado people have triggered archaeological disputes about their origins, their cultural affiliations and development, their disappearance, even their very existence. Cordell said, "The Salado have been viewed as Mogollon, as Anasazi, as a ‘blend’ of Mogollon and Anasazi, and as a ‘blend’ of Anasazi and Hohokam." In a competitiveness which smacked more of football than scholarship, archaeologists from Arizona State University in Phoenix have argued that the Salado people represented a socially complex branch of the Hohokam Puebloan culture while archaeologists from University of Arizona in Tucson have insisted that the Salado emerged indigenously as a socially uncomplicated melting pot of various Puebloan cultures. Some archaeologists, said Reid and Whittlesey, "argued forcefully that there was no distinct Salado Culture and that the term should be dropped."

Without question, Puebloan people from neighboring regions and traditions viewed the Tonto Basin area as a refuge from the persistent drought which gripped the greater Southwest during the 13th through the 15th centuries. They knew that the basin – a transitional zone between pinyon/juniper forested mountains and the Sonoran Desert – received more rain than the Colorado Plateau and the Chihuahuan and Sonoran desert basins. They knew that the Salt River, which drained the basin, held opportunities for irrigation agriculture. They could see that the mountain slopes and desert terrain offered badly needed resources, especially a larger and more diverse game population and more useful wild plant communities. Some groups moved into the Tonto Basin to capitalize on the promise and to forge a distinctive new Puebloan tradition.

Collectively, they followed their own cultural road map, and archaeologists still call the amalgamation "Salado" for want of a better term. During the 13th and 14th centuries, according to Reid and Whittlesey, the Salado people lived in substantial villages comprising residential compounds which surrounded a raised and walled earthen mound and overlooked irrigated fields. They built their extended-family residential compounds of adobe reinforced with river cobbles and posts, enclosing lodges, storage rooms and a central plaza with a wall. They built beehive-shaped granaries within the plaza and rock-lined roasting pits just outside the compound. They probably used their raised earthen mounds in community ceremonies which may have had roots in Hohokam as well as Mesoamerican traditions. Faced with raiding and environmental change in the middle of the 14th century, the Salado people abandoned their communities, and the population consolidated at a few large villages such as the Besh Ba Gowah Pueblo (at Globe, Arizona) or in defensible cliff dwellings at the Tonto Basin perimeter.

During the two and one half centuries that the Salado people occupied the Tonto Basin region, their artisans produced a galaxy of figures on ceramics which would become the tradition’s cultural signature. Using the clay surfaces as their canvases, they painted, for instance, according to Cordell, horned serpents (derived from the icon for a Mesoamerican deity), parrots (native to the heartlands of Mesoamerica), celestial bodies and eyes. The images held such power that one researcher, Patricia L. Crown, has suggested that they signified a "Southwest Regional Cult." (See Crown’s Ceramics and Ideology: Salado Polychrome Pottery.)

The Salado vanished from Tonto Basin in the 15th century, whipsawed by declining resources, devastating floods and searing drought, leaving behind one of the most intriguing and controversial archaeological records in the desert Southwest.

The Upper Pimas

The Upper Pimas, who occupied the vast Sonoran Desert region of northwestern Mexico and southern Arizona when the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, emerged from a common cultural origin but adapted to diverse landscapes. They left an archaeological record which has only been partially investigated by researchers, but they appear to have lived in the region for millennia. They may have arisen from hunting and gathering traditions as old as the last Ice Age, said Charles C. Di Peso in his paper "Prehistory: O’otam," Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest, Volume 9.

According to Bernard L. Fontana ("Pima and Papago: Introduction," Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest, Volume 10), the nomadic Upper Pimas who lived in the western part of the range – in that searingly hot and desiccated region immediately north of the Gulf of California – scratched out a hardscrabble living by capturing rabbits, reptiles, insects and some seafood and by gathering mesquite beans and cactus fruits. Moving in small bands of extended families, they traveled widely and relentlessly in the quest for food. At night, they slept within small circles of stone – "sleeping circles" – which served as no more than windbreaks. They traded with the River and Delta Yumans, exchanging seashells and salt for corn and other food crops.

The Upper Pimas who occupied the central part of the range, which receives some 5 to 10 inches of rainfall per year – twice the precipitation of the western part – lived in hamlets near the mouths of intermontane washes in the summer and adjacent to permanent springs in the winter. Called Papagos, or Tohono O’otam, the central Upper Pima group built water control systems to distribute runoff across their garden plots, where they raised corn, beans and squash during the summer. They hunted game and harvested wild plants – accounting for more than 80 percent of their total annual diet – during the remainder of the year. Their "settlements consisted of several dome-shaped brush structures with slightly excavated floors, separate ramadas (sunshades), outdoor cooking areas, and a small house used as a menstrual seclusion hut," said Cordell.

The Upper Pimas who occupied the eastern part of the range, along the rivers in the more mountainous areas, with 10 to 15 inches of rainfall annually, lived year round in informally arranged villages near their fields, where they raised corn, beans and squash as well as cotton. Additionally, said Cordell, "Hunting and, locally, fishing were important. Deer, peccary, rabbits, iguanas, and quail and doves were hunted for food."

According to Di Peso, some of the Upper Pimas interacted with Puebloan neighbors, especially the Hohokam. They traded for items such as solid clay human figurines, cotton textiles and spindle whorls. They incorporated cultural features such as Hohokam-style ball courts and platform mounds (both with roots in Mesoamerica) into their ceremonial architecture. "In summary," said Di Peso, "it would seem that for 800 years, commencing in the ninth century, the people of Upper Pimeria were very much involved with various cultural intrusions that effected a complicated series of events..." Today, descendents of the Upper Pimas live on a scattering of reservations in southern Arizona.

The Trincheras

The Trincheras people, intermittent and shadowy figures on the archaeological landscape, lived on rocky terraces, in rock-walled and adobe lodges, often near rock-walled community structures, on isolated rocky promontories scattered across the northern Sonoran Desert and the northwestern Chihuahuan Desert. They left behind one of the most substantial – and most confounding – archaeological records of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. Their ruins – called "cerros de trincheras," or "terraced hills," by early Spanish explorers – have yielded information grudgingly to those few researchers who have studied them.

"…the Trincheras culture is still poorly understood," said the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers in its draft Environmental Baseline Document, Arizona Land Border Study Area, Volume 4, March, 1999. "No Trincheras sites with stratified deposits have been excavated, thus precluding the determination of the local chronology. Therefore, it is not possible to delineate cultural development through time, other than in a very generalized manner… …uncertainty exists also about the subsistence and economic practices and the settlement patterns of these people…"

Researchers have known about the trinchera sites for more than a century. In the Seventeenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1895, for instance, W. J. McGee reported that Cerro de Trincheras, a Trinchera site adjacent to the Mexican village Trincheras in Sonora, was "the most elabaorate prehistoric works known to exist in northwestern Mexico. The works comprise terraces, stone walls, and enclosed fortifications, built of loose stones, nearly surrounding two buttes."

Researchers have been mystified by the Trinchera sites – the hundreds of them – from the beginning. Early in the 20th century, Carl Lumholtz, pioneering Norwegian explorer of archaeological ruins in the deserts of North America, said in his book, New Trails in Mexico, found the ruins so puzzling that he thought it was not worth speculating who might have built the original structures. In their paper, "Terraced Hills of Sonora and Their Notices in Literature," University of California Publications in Geography, Volume V, 1931-1932, Carl Sauer and Donald Brand said, "According to current tradition the cerros de trincheras are of the Apache." That proved to be wrong. More recently, researchers have believed that, although a few trinchera sites may have built and occupied as early as A. D. 800, the rest were constructed in late pre-historic times, from A. D. 1100 to 1400. That, too, proved to be wrong. In his paper "Prehistory: Southern Periphery," Handbook of North American Indians, Southwest, Volume 10, di Peso suggested that the Cerro de Trincheras site was "a spectacular hillside trenched defense system…perhaps to protect a marine shell industry." That, too, has proved to be wrong.

In a 1999 report posted on the University of Texas at San Antonio Center for Archaeological Research web site, archaeologist Robert J. Hard said that "recent investigations in northwestern Chihuahua, Mexico have revealed evidence that at least one cerros de trincheras site, Cerro Juanaqueña, was constructed and occupied much earlier than similar Late Prehistoric sites." An immense site with 486 hillside terraces, "Cerro Juanaqueña is similar in scale and form to cerros de trincheras sites dating to the Late Prehistoric period; however, based on numerous radiocarbon dates, Cerro Juanaqueña was constructed and in use by about 1150 B. C., and precedes known sites of similar scale by at least 1500 years." (My emphasis.) Additionally, said Hard, investigators have found evidence of substantial agriculture at Cerro Juanaqueña (again, my emphasis), directly challenging the existing notion that agriculture did not become fully established in the cultures of the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts until the early centuries of the first millennium.

In the Archaeological Society of New Mexico’s La Frontera (annual report no. 25, 1999), archaeologist John R. Roney said that investigations at another trinchera site, Canador Peak, in southwestern New Mexico, have shown that it, too, was constructed and occupied earlier than the late prehistoric sites, but much later than the Cerro Juanaqueña site. Dating from A. D. 200 to 550, Canador Peak helps fill in the time gap between Cerro Juanaqueña and the late prehistoric sites. Inexplicably, at least at this time, the terrace and wall structures of the Canador Peak site closely resemble those of the Cerro Juanaqueña site even though the two are separated in time by more than 13 centuries.

In their paper "Cerro de Trincheras and the Casas Grandes World" in The Casas Grandes World, researchers Randall H. McGuire, Maria Elisa Villalpando C., Victoria D. Vargas, Emilian Gallaga M. reported on the Cerro de Trincheras ruin, perhaps the most extensively investigated and the largest known of the trincheras sites. Truly a late prehistoric site, it dates two and a half millennia more recent than Cerro Juanaqueña. The site has more than 900 terraces, some well over 100 yards in length. "Given the size and visibility of Cerro de Trinchera it seems reasonable at this time to conclude that it was a central place in the Trincheras Tradition," said the archaeologists. During their investigations, they found the ruins of a large complex of architectural features, including, for example, more than 300 round or rectangular flimsy dry cobble-wall rooms and numerous jacales on the terraces; a spiral-shaped cobble-wall plaza, possibly for private ceremonies, on the hill’s crest; and an elongated (60 feet by 220 feet) oval excavation, possibly for public ceremonies, at the hill’s base. They found no evidence to support di Peso’s suggestion that the site might be a fortress to protect a shell industry or other archaeologists’ proposals that it could some sort of an outlier of another culture. In fact, said the authors, "…it is striking how distinctive the site is and how little evidence there is for long-distance exchange."

At this point, archaeologists cannot track the development nor the continuity (or discontinuity) of the Trinchera tradition. They cannot say what purpose the cerros de trincheras served, although they speculate that they functioned as fortresses, residences, terraced gardens, ceremonial communities, signal stations, astronomical observatories and multiple purpose communities. Sauer and Brand said that one archaeologist thought the Trincheras may have used "the terraces for some very special crop, such as grapes! If we assume," Sauer and Brand continued, "that this amazing population carried soil annually to replenish the terraces for such a precious crop, we can imagine some rare vintage being produced here. One might suggest, however, the cultivation of peyote or of a pre-Columbian marihuana to produce more effectively the hallucinations necessary for such strange behavior."

Next month, in "Life on the Margin, Part II," we will review some of the marginal tribes of southern New Mexico, western Texas and Mexico’s northern Chihuahua.

![]()

"Paleo-Indians" (Part 1)

Desert Archaic peoples( Part 2)

Desert Archaic peoples - Spritual Quest (Part 3)

Native Americans - The Formative Period (Part 4)

Voices from the South (Part 5)

The Mogollon Basin and Range Region (Part 6)

The Mogollon - Their Magic (Part7)

Hohokam the Farmers (Part 8)

The Hohokam Signature (Part 9 )

The Anasazi (Part 10)

The Anasazi 2 (Part 11)

The Great Puebloan Abandonments (Part 12)

Paquime (Part 13)

When The Spanish Came (Part 14)

Life on the Margin (Part 15) This page

Life on the Margin (2) (Part 16)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 1 (Part 17)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 2 (Part 18)

The Outside Raiders (Part 19)

The Enduring Mysteries (Part 20)

Some Sites to Visit (Final Part)

Pueblo Rebellion

Profile Of An Apache Woman

Cochise and the Bascom Affair

Geronimo's Last Hurrah

Books on Native American healing

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms

SEARCH THIS SITE

Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park

The movie Stagecoach, in 1939 introduced two stars to the American public, John Wayne, and Monument Valley. Visiting Monument Valley gives you a spiritual and uplifting experience that few places on earth can duplicate. Take a look at this spectacular scenery in this DesertUSA video.

Glen Canyon Dam - Lake Powell Held behind the Bureau of Reclamation's Glen Canyon Dam, waters of the Colorado River and tributaries are backed up almost 186 miles, forming Lake Powell. The dam was completed in 1963. Take a look at this tremendous feat of engineering - the Glen Canyon Dam.

Canyon de Chelly National Monument

Canyon de Chelly NM offers the opportunity to learn about Southwestern Indian history from the earliest Anasazi to the Navajo Indians who live and farm here today. Its primary attractions are ruins of Indian villages built between 350 and 1300 AD at the base of sheer red cliffs and in canyon wall caves.

___________________________________

Take a look at our Animals index page to find information about all kinds of birds, snakes, mammals, spiders and more!

Click here to see current desert temperatures!