Mogollon Magic

Mysterious and Evocative Images

Across their range – from southeastern Arizona and northeastern Sonora through southern New Mexico and northern Chihuahua into western Texas – the Mogollon people left us with stunning galleries of mysterious and evocative images painted or chiseled on surfaces of stone. In rudimentary observatories and mountain crevasses split by the rays of the sun, they tracked the annual passage of our star and the coming and going of the seasons. In sequestered rock alcoves, caves and village ceremonial chambers, their holy men – or shamans, people who had access to the spirit world – cached sacred artifacts, their instruments of magic. On the surfaces of ceramic vessels, their potters, especially those of southwestern New Mexico, produced what are apparently visualizations of Mogollon religious beliefs and legend, including deities, mythological figures, ceremonial dancers, animals, birds and symbolic geometric designs.

While the ruins of their villages and the flotsam and jetsam of their lives tell us much about how the Mogollons sheltered, clothed, provisioned and defended themselves, the images on stone, the sites for celestial watches, the caches of sacred objects, and the paintings on ceramic vessels give us only the vaguest notion about how they nourished their souls. The clues leave us mystified about how they saw their place in the universe, explained the origins of the tribe, chose their village sites in the desert, regarded the epics of their past, commemorated the lives of their ancestors, overcame their anxieties about survival, sought spiritual help for their injured and sick, or petitioned their deities for supernatural intervention and sustenance. We can sense their overriding fears of drought, storm, enemies, disease and, perhaps, witchcraft. We can imagine the ritual, the ceremony, the celebration, the dance. Obviously, we have no artifactual records of the chants of their shamans and medicine men, the stories around their evening campfires or the sounds of their drums. In the end, we know little about the nonmaterial dimensions of their lives.

While the ruins of their villages and the flotsam and jetsam of their lives tell us much about how the Mogollons sheltered, clothed, provisioned and defended themselves, the images on stone, the sites for celestial watches, the caches of sacred objects, and the paintings on ceramic vessels give us only the vaguest notion about how they nourished their souls. The clues leave us mystified about how they saw their place in the universe, explained the origins of the tribe, chose their village sites in the desert, regarded the epics of their past, commemorated the lives of their ancestors, overcame their anxieties about survival, sought spiritual help for their injured and sick, or petitioned their deities for supernatural intervention and sustenance. We can sense their overriding fears of drought, storm, enemies, disease and, perhaps, witchcraft. We can imagine the ritual, the ceremony, the celebration, the dance. Obviously, we have no artifactual records of the chants of their shamans and medicine men, the stories around their evening campfires or the sounds of their drums. In the end, we know little about the nonmaterial dimensions of their lives.

The Rock Art

One summer afternoon, I sat with Alex Mares, a Texas Parks & Wildlife ranger who is half Navajo and half Hispanic, in a small rock alcove in the heart of the range of basaltic hills at Hueco Tanks, a state historical park in far West Texas. Through the narrow entrance, we could see the creosote- and mesquite-covered desert floor and the black granite hill immediately to the west. On the ceiling, just above our heads, hovered several black and white images of goggle-eyed, limbless and trapezoidal-shaped figures which seemingly bear unmistakable connections with Tlaloc, the goggle-eyed Mesoamerican god of storm and rains. The figures stared down at us as if we had intruded into an alien world.

"I got caught in a thunderstorm out in this part of the park late one afternoon," said Alex, "and I took shelter in here. It became a real downpour. A lot of lightening and thunder. While I waited, rain water began to cascade down the slope of the hill above us, and it fell across the entrance like a bridal veil. After a while, the sun came out, and the rays shone right through the veil. Reflections lit up these Tlaloc figures with a shimmering and sparkling light. It felt supernatural and spiritual."

Kay Sutherland, a cultural anthropologist with St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, has suggested that Mogollon shamans may have painted or chiseled images (archaeologists call painted images "pictographs" and chiseled images "petroglyphs") on stone surfaces and then used the figures as a mystical gateway to the spirit world. If so, the abundance, diversity, distribution and stylistic consistency of much of the Mogollon rock art suggest an intense, widespread and pervasive spiritual life, especially in the mountain foothills and desert basins of southern New Mexico, western Texas and northern Chihuahua.

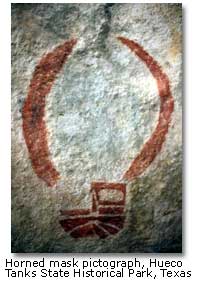

Scattered across this 100,000 square-mile span, which encompasses the Mimbres branch of the Mogollon to the west and the Jornada branch to the east, we find large panels of stone which bear "Masks and faces with almond eyes and abstract decoration, horns, feathers, and pointed caps; mythical beings with round staring eyes; large blanket designs; animals with bent legs and formal decorative patterns on their bodies; horned serpents; flying birds and spread-winged eagles; turtles, tadpoles, fish, and insects; corn, cloud terraces, and rainbows," according to Polly Schaafsma, the foremost authority on the rock art of the deserts of the Southwest.

Investigators have found more than 3,000 Jornada Mogollon rock paintings, or pictographs, at Hueco Tanks alone. They have documented images of the Tlaloc storm god, the Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatal plumed and horned serpent deity, elaborately costumed dancers, religious masks, caricatured faces, storm symbols, corn, animals, birds and reptiles as well as many geometric designs. They have found more pictographs of deities, dancers and masks at Hueco Tanks than any place else in the entire Southwest. Texas A&M chemists and rock art dating specialists Marvin Rowe and Marian Hyman have run radio carbon dating analyses which suggest that Jornada Mogollon shamans may have painted some of the images as early as the seventh century. Most investigators think the Jornada Mogollon continued painting images at Hueco Tanks until well into the first millennium. Computer specialists Evelyn Billo and Robert Mark, Rupestrian CyberServices, Flagstaff, Arizona, have used digital techniques to enhance photographs of Hueco Tanks rock art, offering astonishingly more detailed looks at images which had been thought lost forever to time, weather and vandalism.

Investigators have found more than 3,000 Jornada Mogollon rock paintings, or pictographs, at Hueco Tanks alone. They have documented images of the Tlaloc storm god, the Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatal plumed and horned serpent deity, elaborately costumed dancers, religious masks, caricatured faces, storm symbols, corn, animals, birds and reptiles as well as many geometric designs. They have found more pictographs of deities, dancers and masks at Hueco Tanks than any place else in the entire Southwest. Texas A&M chemists and rock art dating specialists Marvin Rowe and Marian Hyman have run radio carbon dating analyses which suggest that Jornada Mogollon shamans may have painted some of the images as early as the seventh century. Most investigators think the Jornada Mogollon continued painting images at Hueco Tanks until well into the first millennium. Computer specialists Evelyn Billo and Robert Mark, Rupestrian CyberServices, Flagstaff, Arizona, have used digital techniques to enhance photographs of Hueco Tanks rock art, offering astonishingly more detailed looks at images which had been thought lost forever to time, weather and vandalism.

Hueco Tanks holds a treasure-trove of Jornado Mogollon pictographs. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s Three Rivers Petroglyph Site, located on the western flank of southern New Mexico’s Sacramento Mountains, holds an even greater abundance of Jornada Mogollon rock art, in this instance, more than 20,000 Jornada petroglyphs. The Three Rivers site is, according to renowned Native American art historian J. J. Brody, "...one of the densest concentrations of art in any medium anywhere in the world." Helen Crotty, well known rock art documentation specialist, said, "Mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects are present in a variety of recognizable species as well as in stylized and semi-abstract renditions. Human figures, especially faces or masks are also abundant and seemingly endlessly diverse. The numerous geometric designs are equally intriguing..." Schaafsma said that the "...imagery documents much that is significant in the history of ongoing religious beliefs and practices in the Pueblo Southwest." Meliha S. Duran, co-author (with Helen Crotty) of the report on the most important archaeological study of Three Rivers, said that the images "...encode important information on the world view, cosmology, and religion of these peoples [the Jornada Mogollon]."

Archaeologists have recorded more than six dozen other significant Jornada Mogollon rock art sites with thousands more images in southern New Mexico, western Texas and northern Chihuahua. Most lie along the Rio Grande, near mountain foothills and streams, beside ancient trade routes and even near prehistoric turquoise mines. Almost certainly, there are many more sites, especially in Chihuahua, which has never been fully surveyed.

Researchers appear to believe universally that rock art of costumed dancers, masks, mythological figures and certain symbols speaks to ceremony, ritual, magic and spirituality, but the scholars run into a wall of frustration when they try to interpret or even classify the images.

For instance, in attempts to explain the figure "X" – one of the simplest and most common abstracted symbols in the rock art of the Jornada Mogollon region – one investigator says that it represents the shape of a roadrunner’s track and that the symbolic indeterminate direction of the bird’s travel served through magic to confuse tribal enemies. Another researcher says, no, the "X" can’t be a roadrunner’s track; it’s clearly a prehistoric shorthand representation of the prehistoric jaguar priesthood of Mesoamerica, where a similar symbol appears on images of the jaguar religious figures. A third investigator says, no, no, the "X" can’t be a roadrunner’s track. It can’t be a jaguar priesthood symbol. It’s not even an "X." It’s a "K."

Most investigators believe that the goggle-eyed figures like those at Hueco Tanks show undeniable roots in the Mesoamerican storm god Tlaloc. Polly Schaafsma said, "Comparisons with Mexican depictions of Tlaloc suggest strongly that, in fact, it is he who is being represented through the Jornada [Mogollon] style." She said, further, the figure is "...widely represented, occurring at least once in nearly every Jornada Style rock art site on site cluster." However, at least one other scholar, Helen Crotty, has suggested that "...the outsized eyes and the limbless trapezoidal figure are reminiscent of the Archaic Barrier Canyon Style f igures..." which occur, not in Mesoamerica, but in Utah.

igures..." which occur, not in Mesoamerica, but in Utah.

Kay Sutherland and another researcher, Regan Giese, examined a Jornada Mogollon figure of an animal painted on the ceiling of a rock shelter near Fort Hancock, in western Texas, and they declared it is clearly the representation of a bear. Another investigator, John Green, examined the same figure, and he suggested that the figure is the representation of a porcupine.

While acknowledging that much of the rock art is, without question, related to Jornada Mogollon spirituality, a few researchers have suggested that some images may have served to mark prehistoric clans or social groupings, territorial boundaries, important trails and water sites.

The Mogollon peoples left their signature rock art record in the Jornada and Mimbres regions, but they also produced two other, less widespread styles – one called "Mogollon Red," the other, "Reserve Petroglyph" – in the western regions, near the New Mexico and Arizona border. Both seem to have appeared between A. D. 1000 and 1400.

According to Schaafsma, the Mogollon Red, usually small reddish figures painted in rock alcoves, includes two types of human figures, one wearing a one-horned headdress, the other holding an apparent staff. The style also includes an array of geometric designs. It appears to derive cultural inspiration from the Hohokam peoples to the west.

The Reserve Petroglyph style, largely confined to the San Francisco and Tularosa River drainages, includes human figures wearing one-horned headdresses or playing flutes. It also includes human and animal tracks and geometric designs. Most impressively, suggests Schaafsma, it includes large animals, perhaps mountain lions or coyotes, pecked into stone faces high on sequestered cliff faces. The style evidently draws on the Anasazi culture to the north and the Jornada Mogollon culture to the east for artistic inspiration.

Collectively, the Mogollon peoples bequeathed us great outdoor galleries of suggestive and evocative rock art, but they left few keys to its meaning.

Mogollon Sky Watchers

Although we can read little more than isolated fragments of the spiritual stories suggested by the symbols on stone, we can surmise that many Mogollon religious ceremonies revolved around the annual advances and retreats of the sun, celestial events in the night sky, the passage of the seasons, and the timely nourishment or untimely failure of rainfall. We can visualize prehistoric farmers appealing to their deities for supernatural help with crops in a diverse landscape which is characterized by dry spring times, frequent drought, often violent late summer thunderstorms, and – in the higher elevations – early frosts.

We have evidence that the Mogollon tracked the movement of the sun and probably certain planets and stars with reverence and care, presumably using their progression as a celestial calendar for scheduling spring planting and annual ceremony and ritual. For instance, at the ruins of Casa Malpais, a Mogollon agricultural community (7000 feet above sea level) built on basalt terraces above the Little Colorado River in eastern Arizona, we find an apparent astronomical observatory with a roughly circular stone wall measuring some 85 feet in diameter and three to four feet in height. The wall has doorways and a solar petroglyph aligned with the sun’s path during annual equinoxes and solstices. Near the same ruin, we find astronomically aligned shrines, underlining the importance to the farmer of tracking the majestic movements of stars and planets and anticipating the changes of the seasons. Archaeologists working in the Mogollon region have found other sites, including two in the Franklin Mountains of far West Texas, which apparently served as astronomical observatories. They will likely find more in future surveys and studies.

Between the observatories and the rock art, we see evidence – like a diaphanous web – of a complex spiritual belief system which in some mysterious way integrated celestial movements and seasonal change with supernatural powers, ceremony, ritual and agriculture, possibly with echoes from the ancient days of hunting and gathering. In the rock art, we see images of deities – for instance, the Tlaloc storm god – whom the Mogollon may have petitioned for the desert’s most prized resource, water. There are figures of costumed dancers, horned (a carryover from the days of the hunters?) headdresses and ghost-eyed masks which the Mogollon may have used in a ceremonial call for water. An abundance of symbols survive, such as pyramid-shaped cloud altars, lightening zigzags and rainbows, which the Mogollon may have employed in an invocation for rain for their crops. Renditions of corn stalks appear and, especially in the western Mogollon region, the image of the hump-back flute player Kokopelli recurs, which the Mogollon may have associated with fertility and bountiful harvests. We can suspect – it is no more than that – that the Mogollon may have scheduled their ceremonies to coincide with the solstices or equinoxes. We know that some historic tribes held celebrations around those times of the year, apparently in accordance with ancient tradition.

The Tools of the Shamans

Our impression that the Mogollon viewed life from a powerful and pervasive spiritual perspective is reinforced by finds of caches of objects which appear to be sacred. These included ceremonial "prayer" sticks (or pahos), ceremonial pipes, ritual bows and arrows, animal effigies, bear and mountain lion fetishes, feathers, plants, crystals and semi-precious minerals. Certainly, the objects had no apparent practicable use.

Archaeologists suspect, for one example, that shamans may have produced pahos for use in ceremonies. In carving a paho, a shaman sharpened the bottom end to a point. He decorated the shaft with elaborate geometric designs. He often adorned the top end with a pulley-shaped disk which served as a platform for a small mushroom-shaped carving. In other instances, a shaman topped a paho with a masked human figure. Archaeologists have found pahos at various sites, for example, in the Mimbres Mogollon regions.

Archaeologists also have found some evidence which suggests that Mogollon shamans used psychoactive plants to induce trances, a state which conveyed them into the spirit world. The archaeologists have discovered, for instance, caches of the seeds of the sacred datura, a powerful hallucinogenic (and potentially deadly) herb which produces showy white blooms with lavender tints. They suspect that mushroom-shaped carvings atop pahos point to the use of psychoactive fungi, which may have been acquired through trade with tribes to the south. They would not be surprised if the Mogollon shamans made sacred pilgrimages to southwestern New Mexico’s Florida Mountains to collect peyote, a psychoactive cactus still used by some Native Americans in various ceremonies. Investigators of Mogollon sites have found ceramic and ground stone pipes with the residue of tobacco, a narcotic which produced smoke clouds possibly associated magically with rain clouds.

The Story in Clay

While not a Rosetta Stone, images painted on ceramics produced by the Mimbres branch of the Mogollons, in southwestern New Mexico, do yield some intriguing suggestions about the meaning of the Mogollon belief system.

The Mimbres, centered in the southern Gila Wilderness, lived in their region for nearly a millennium, from roughly A. D. 200 to 1150. For approximately half that time, according to J. J. Brody, they produced typical Mogollon plain brown or red ceramic vessels. Then, about 650 or 700, Mimbres potters began to experiment with painted designs on vessel surfaces. By about 800, they had developed a signature pottery, which bore black designs on white backgrounds and would become works of art.

In particular, "Bowl interiors...were treated as artists’ canvasses," said J. J. Brody. "That these vessels were used as art rather than as containers is confirmed by the many thousands of Mimbres pots buried with their dead which show no other use than service as funerary pottery.

"About 10,000 Mimbres pottery paintings are known today... Yet, so large a proportion...was buried with their dead that the art was virtually unknown in its time outside of Mimbres territory.

"Most painted Mimbres pottery was ritually ‘killed’ by being smashed or having a hole punched in it at the time of burial. Usually a bowl was placed over the head of the dead person, who could then look eternally into the picture that was painted on its inner surface."

The earliest generations of Mimbres potters who produced the black on white ceramics used bold heavy, often wavy lines to paint geometric designs which incorporated features such as scrolls, nested squares, cross hatching and spirals on the inner surfaces of the bowls. Rarely, they included stylized images of animals, birds and reptiles.

Middle generations painted finer, often straight parallel lines in developing geometric designs which involved elements such as hachure, rectangles, v-shapes, chevrons and scrolls. More often than in the past, they included figurative representations of wildlife.

The final three or four generations of Mimbres potters produced a crescendo of finely painted geometric designs and representational figures. "...there was an explosion of creativity that generated the development of an incredibly varied and sophisticated design vocabulary," said authority Catherine J. Scott. The figurative paintings portrayed "mammals of various kinds, birds, fish, insects, and hybrid creatures, as well as human figures," she said. She added, "The complexity of geometric design, the great variety of motifs and their arrangement, and the subtlety of figurative depictions have made it difficult to map out the later development... ...it is just these qualities that made the study of Mimbres pottery so rewarding."

In the last century before the Mimbres vanished from southwestern New Mexico, around 1150, the potters produced what is perhaps the most complete record of the nonmaterial dimensions of the lives of the Mogollon people. They gave us fleeting glimpses of connections with distant Mogollon rock art, celestial watches and shamanistic celebration and ritual. We see images of Tlaloc figures, animals and birds similar to those of Hueco Tanks and Three Rivers. We see images which seem to represent, for instance, the moon, which would have been observed by the Mogollon sky watchers. We see representations of pahos, the shamans’ magic staffs.

We even see snapshots apparently connected with everyday life. J. J. Brody said, "Most Mimbres figurative paintings represent only a single creature, and about half of these are birds or nonhuman mammals. Rabbits, mountain sheep, deer and antelope make up the majority of the latter, while most of the birds are waterfowl or other game birds. Humans make up about fifteen percent of all images and fish another ten percent. The remaining twenty-five percent are divided fairly evenly among insects, amphibians, reptiles, and mythic creatures...

"What does it mean to represent food animals [such as rabbits, mountain sheep, deer and game birds]? Why are rabbits, the most common food animal of [late] Mimbres times, and mountain sheep, among the least common, the two mammals most often pictured by Mimbres artists? Are the paintings prayers for hunting success? Are they offerings of thanks commemorating successful hunts? Are they prayers for fertility and increase?"

"...I believe that many of the scenes on the bowls are depictions of myths," said researcher Pat Carr, "the very myths the [Mimbres] lived by and for. From a study of the myths of any culture, we are able to understand the ethical precepts, the inspirations, and the beliefs of that culture, and thus if we can discover the myths current in the Mimbres Valley during the eleventh century, we may be able to understand the ideals, the philosophical bent, and ultimately the very patterns of behavior of the ancient [Mimbres] Indians."

We would also be able to broaden our understanding of the ideals, philosophy and behavior of the Mogollon culture as a whole.

For additional reading, see Archaeology of The Southwest, Second Edition, by Linda Cordell; Mimbres Painted Pottery by J. J. Brody; Mimbres Pottery by Tony Berlant, J. J. Brody, Catherine J. Scott and Steven A. LeBlanc; Mimbres Mythology, Southwestern Studies, Monograph No. 56, by Pat Carr; Indian Rock Art of the Southwest by Polly Schaafsma; Three Rivers Petroglyph Site: Results of the ASNM Rock Art Recording Field School by Meliha S. Duran and Helen K. Crotty; "Spirits From the South," The Artifact, Vol. 34, Nos. 1 & 2, 1996, by Kay Sutherland. All these sources should be available in any university library.

More...

"Paleo-Indians" (Part 1)

Desert Archaic peoples( Part 2)

Desert Archaic peoples - Spiritual Quest (Part 3)

Native Americans - The Formative Period (Part 4)

Voices from the South (Part 5)

The Mogollon Basin and Range Region (Part 6)

The Mogollon - Their Magic (Part 7) This page

Hohokam - the Farmers (Part 8)

The Hohokam Signature (Part 9 )

The Anasazi (Part 10)

The Anasazi 2 (Part 11)

The Great Puebloan Abandonments (Part 12)

Paquime (Part 13)

When the Spanish Came (Part 14)

Life on the Margin (Part 15)

Life on the Margin (2) (Part 16)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 1 (Part 17)

The Athapaskan Speakers Part 2 (Part 18)

The Outside Raiders (Part 19)

The Enduring Mysteries (Part 20)

Some Sites to Visit (Final Part)

Pueblo Rebellion

Profile Of An Apache Woman

Cochise and the Bascom Affair

Geronimo's Last Hurrah

Books on Native American healing

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms