Pottery - Southwest Collectibles

Native American Pottery

by Jay W. Sharp

For some 20 centuries, the Native American potters of the Southwestern deserts have produced ceramic vessels that give expression to their heritage. Through their distinctive and enduring work, they have marked the boundaries and durations of their traditions, the cultural reach of their people, and the courses of their trade routes and migrations. In the bodies of their vessels, they have left clues to sources of raw materials and techniques of manufacture. In their designs, they have embraced symbols of their religious and mythological beliefs, and they have revealed their cultural debts to other, sometimes distant, peoples. Today, modern potters offer the collector a treasure trove of Southwest Native American history and artisanship that emerged largely from prehistoric Puebloan village farming communities and the mobile Navajo and Apache hunting, gathering and raiding tribes.

The Craft - Prehistorically

The early potters learned their craft from peoples to the south, from Mexico, introducing it into the Southwest early in the first millennium. The potters — almost exclusively women, in all likelihood — may have produced their ceramics at manufacturing centers or in their homes.

Typically, they dug clay from nearby (often secret and carefully guarded)

deposits. They picked it free of impurities such as pebbles, stems and leaves.

They pulverized it with mortars and pestles and grinding stones. They mixed it

with a temper such as sand, finely crushed rock or even finely crushed pottery

fragments (sherds), which would help prevent a vessel from shrinking and cracking

during the drying and firing process. They soaked the clay and temper mix with

water to create a pliable mass, ready to be transformed into a vessel.

Typically, they dug clay from nearby (often secret and carefully guarded)

deposits. They picked it free of impurities such as pebbles, stems and leaves.

They pulverized it with mortars and pestles and grinding stones. They mixed it

with a temper such as sand, finely crushed rock or even finely crushed pottery

fragments (sherds), which would help prevent a vessel from shrinking and cracking

during the drying and firing process. They soaked the clay and temper mix with

water to create a pliable mass, ready to be transformed into a vessel.

The potters kneaded and flattened the clay/temper mix to squeeze out air

bubbles, which could expand and burst during a firing. They rolled the mix into

short coils, or ropes, each roughly the size of a finger. They may have made

a tight, flat spiral of one strand, using their hands to mold it into a solid

base. They laid another strand around the top of the perimeter of the base, and

they laid other strands one on top of the other to build up the sides of their

vessel. With their hands and fingers, they pressed the strands together to join

them together, into a solid wall. They may have used stone basins or large potsherds

as molds for  shaping a vessel. They used tools such as flaked stone, deer bones

or potsherd scrapers to dress the vessel walls. (Some of the early potters formed

vessels by using a paddle to shape the walls around a large stone or other object

known as an anvil.)

shaping a vessel. They used tools such as flaked stone, deer bones

or potsherd scrapers to dress the vessel walls. (Some of the early potters formed

vessels by using a paddle to shape the walls around a large stone or other object

known as an anvil.)

After treating, polishing, decorating, and drying a vessel, they fired it, probably along with other vessels, in an open fire, a shallow pit or a rude kiln, using wood or perhaps dried dung as fuel.

The earliest Southwest potters — probably those of the Hohokam culture, in southern Arizona — usually made plain brownish or gray vessels called utility wares. With the passage of centuries and the geographic expansion of the technology, the potters raised their craft to the level of art. They not only created graceful and imaginative new vessel shapes, they drew on paints and materials derived and processed from minerals and plants to produce ceramics with elegant surfaces, sparkling glazes, elaborate surface patterns and designs, and richly symbolic and variously colored imagery. They used fine paint brushes fashioned from the leaves of plants such as a narrow-leaf yucca.

At their artistic peak, according to the History of Ceramics Internet site, the Hohokam potters, for example, produced vessels from a buff-colored clay painted with a red slip and decorated with "lively forms in 'simplified realism.'" The Anasazi potters, of the Four Corners region, "developed tight geometric motifs in symmetrical repeated patterns with black on white ware."

Late prehistoric Puebloan potters of the upper Rio Grande — many of them descendants of the Anasazi — produced new vessel forms, and they explored new designs that often incorporated images of birds, feathers and sun symbols. The potters of the Mimbres branch of the Mogollon tradition — which spanned eastern Arizona, southern New Mexico, western Texas and Mexico's northern Chihuahua — crafted simple, hemispheric-shaped bowls decorated with sophisticated black on white images of humans, animals, mythic figures and geometric abstractions. (The Mimbres potters would have been astounded to learn that their bowls, often plundered from ancient village sites, now sell for as much as $100,000 in the illicit marketplaces for antiquities.) The potters of Casas Grandes, a late prehistoric Puebloan tradition centered in northwestern Chihuahua, created vessels with multicolored designs of highly variable geometries, real animals, mythological beings and abstracted human figures.

As the Yale University Press said in its Internet site comments about the book Casas Grandes and the Ceramic Art of the Ancient Southwest, "In the flourishing ancient Indian communities of the American Southwest and northwest Mexico, master potters created ceramic arts that are considered among the most accomplished in the world. The symbolic imagery and distinctive local styles of the region are unmistakable..."

Modern Southwest Native American potters, while always mindful of their cultural roots, have reached for whole new levels of art. "You're always talking to the pot when you are making it — telling it of your feelings — and when you finish a pot you blow life into it and it is given life," said the Acoma Pueblo's Wanda Aragon, according to Rick Dillingham, Acoma and Laguna Pottery.

The Craft Today

The Craft Today

In the Indian markets and specialty retail stores at reservations, visitor centers,

trading posts, communities and festivals across the Southwest, you will find

that — while holding true to their cultural legacy — the top Native American

potters view each vessel as a three-dimensional surface with limitless possibilities

for shaped, molded, sculpted and painted designs.

While adhering to the ancient methods for crafting their vessels, they will make every piece a distinctive creation. If you become drawn to Southwest Native American pottery, your collection will inevitably stand unique.

As you consider vessels for a collection, you will discover, as authority Robert F. Nichols says, a diversity that flows from varying cultural legacies as well as from individual family traditions, personal innovations and locally available mineral and plant materials. For example, in accordance with their tradition, says Nichols, potters of the Cochiti Pueblo can use a broad range of designs in their work while those of the Santa Domingo Pueblo must avoid using certain designs imbued with religious meanings. In what has become a family tradition, the Bacas, of the Santa Clara Pueblo, have become known for distinctive melon pots (ribbed bowls that resemble melons). Their tradition began with an original innovation attributable to an individual, Angela Baca. Reflecting the colors of clays locally available to them, the potters of the Acoma Pueblo produce white pots; those of the Zia Pueblo, red pots; those of the Hopi Pueblo villages, beige pots.

In selecting pots for a collection, you have a broad range of options. For

instance, you can simply choose pots that appeal most to your taste. Or you might

opt for vessels from a particular pueblo, the Navajo or Apache wares, a certain

family, or an individual artist. You might collect vessels with paintings of

mythological figures such as Kokopelli, the Hero Twins, the Corn Maidens or the

Plumed or Horned Serpent. You may become enamored by the charming Cochiti Pueblo "Storyteller" ceramics,

which feature figures of wise elders telling tales of his people to rapt children.

You might be taken by the utilitarian pots of the Tarahumara Indians, a tribe

that still closely follows a traditional lifestyle in Copper Canyon, in Mexico's

state of Chihuahua. You might prefer replicas — for instance, of the famous

Mimbres or Casas Grandes bowls — made with the same manufacturing techniques

and designs used by the prehistoric potters. However you choose to structure

a collection, each vessel will speak to the cultural origins of prehistoric potters.

A few of many examples of producers of high quality Native American ceramics

include:

In selecting pots for a collection, you have a broad range of options. For

instance, you can simply choose pots that appeal most to your taste. Or you might

opt for vessels from a particular pueblo, the Navajo or Apache wares, a certain

family, or an individual artist. You might collect vessels with paintings of

mythological figures such as Kokopelli, the Hero Twins, the Corn Maidens or the

Plumed or Horned Serpent. You may become enamored by the charming Cochiti Pueblo "Storyteller" ceramics,

which feature figures of wise elders telling tales of his people to rapt children.

You might be taken by the utilitarian pots of the Tarahumara Indians, a tribe

that still closely follows a traditional lifestyle in Copper Canyon, in Mexico's

state of Chihuahua. You might prefer replicas — for instance, of the famous

Mimbres or Casas Grandes bowls — made with the same manufacturing techniques

and designs used by the prehistoric potters. However you choose to structure

a collection, each vessel will speak to the cultural origins of prehistoric potters.

A few of many examples of producers of high quality Native American ceramics

include:

San Ildefonso Pueblo — Typically, the potters of San Ildefonso, roughly 20 miles northwest of Santa Fe, produce highly polished black vessels with black matte imagery. Beginning early in the 20th century, the pueblo's Maria Martinez, her husband Julian, and their descendants revived the art of Puebloan pottery making, which had faded after the introduction of commercial tin wares. Maria's exquisite ceramics have become world famous, often finding places in museums. Today, even her small bowls may sell for thousands of dollars.

Santa Clara Pueblo — The potters of Santa Clara, just a few miles north

of San Ildefonso, craft highly polished black and reddish brown ceramics with

heavy vessel walls and carved bas relief imagery. The Baca family, with the ribbed

melon bowls, probably ranks as the best known of the pueblo's potters, but others,

exploring other avenues of creativity, have helped expand the boundaries of their

craft.

Santa Clara Pueblo — The potters of Santa Clara, just a few miles north

of San Ildefonso, craft highly polished black and reddish brown ceramics with

heavy vessel walls and carved bas relief imagery. The Baca family, with the ribbed

melon bowls, probably ranks as the best known of the pueblo's potters, but others,

exploring other avenues of creativity, have helped expand the boundaries of their

craft.

Cochiti Pueblo — In 1964, Cochiti's Helen Cordero, inspired by the ancient Puebloan tradition of making figurines, created her first ceramic storyteller, in essence, a family portrait of her grandfather surrounded by five grandchildren (including herself) listening to his tales. Her work touched a Puebloan nerve — the tradition of the elders telling stories and singing songs to the children. "Today," said Barbara Babcock in her book The Pueblo Storyteller: Development of a Figurative Ceramic Tradition, "as many as three hundred potters in thirteen pueblos have created storytellers . . . and the storytellers are not only men and women, but also mudheads [ceremonial masked dancing figures], koshares [also masked dancing figures], bears, owls and other animals...often with children numbering more than one hundred!"

Acoma Pueblo — The artisans of Acoma — a spectacular, early second millennium, Anasazi-rooted village atop a 350-foot high mesa some 70 miles west of Albuquerque — produce dazzlingly white ceramics from their nearest sources of clay. According to Carol Snyder Halberstadt (see her Internet site), "Designs...include polychrome rainbow bands, birds (parrots or macaws), deerÉ[and] black or dark brown and white abstract stylized adaptations of ancient Anasazi, Mogollon, and Mimbres wareÉ Hatching symbolizes rain, stepped motifs represent clouds, double dots stand for raindrops... Some of the better known Acoma potters come from the Lewis, Chino, Cerno, Torivio, Aragon, Garcia, Antonio, Concho, Vallo, and Sandoval families, according to the Canyon Country Originals Internet site.

Zuni Pueblo — Inspired by some gifted teachers and the Smithsonian Institution, the potters of Zuni, near the Arizona/New Mexico border, where Coronado arrived with his conquistadors in 1540, revived their craft in the second half of the 20th century. Some have returned to the prehistoric methods for making pots.

"Traditional Zuni designs include water symbols such as tadpoles, frogs,

dragonflies and the Zuni 'rain bird,' as well as flower rosettes and deer..." according

to The Zuni Connection Internet site. "Traditional forms include the stepped-edge

cornmeal bowl (also known as  cloud or prayer bowls), bird effigies and vessels

in such forms."

cloud or prayer bowls), bird effigies and vessels

in such forms."

Hopi Pueblo — Stimulated by growing interest from outsiders, the potters of the Hopi villages, in northwestern Arizona, rejuvenated their art from fading traditions late in the 19th century.

Typically, the potters decorate their usually beige-colored pots with designs of "eagles, parrots, roadrunners, migration patterns, eagle tail, kiva designs, pueblo style villages, rain & rain clouds, lightning, water waves and other life germinating symbols such as corn," says the Hopi Market Internet site. Often the Hopi potters produce small, thin-walled vessels with precisely detailed imagery. Hopi families with well-known potters include the Nampeyos, the Namingas, the Navasies and the Tahbos.

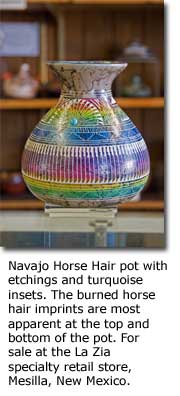

Navajos — The Navajo people — once hunters and wild plant gatherers from the Four Corners region — produced relatively crude, pitch-covered utilitarian wares with practical uses such as holding water and cooking meals. Resourceful and innovative, however, Navajo potters began to make ceramics, often in non-traditional ways, in answer to rising tourist demand in the 20th century, often using Puebloan design motifs. More recently, however, they have begun creating the strikingly unique "Horse Hair" pottery, which bears the ethereal imprint of horse hair scorched into the vessel surface during the firing process. Still more recently, various Navajo artists have integrated iridescently colored etchings and turquoise insets with the horsehair imprints to create extraordinary works. A few of the better known Navajo potters include Hilda Whitegoat, Tom Vail, Geri Vail, Susie Charlie and Myron Charlie.

Apaches — The Apaches, specifically the Jicarilla group from northern New Mexico, have for centuries produced ceramics from clay with a high proportion of mica, crystalline minerals that often occur in layers. Originally, the Apache potters thought of the glittering, bronze-colored vessels — lightweight, strong, heat retentive — as no more than high quality utility ware perfectly suited for cooking and food and water storage. Recently, however, they have found a market among discerning purchasers, who have realized that micaceous ceramics can add a distinctive warmth, character and charm to a collection. Jicarilla Apache potters Felipe Ortega and Lydia Pesata have played key roles in elevating micaceous ceramics to the level of art.

Mata Ortiz — The consummate potters of Mata Ortiz, a remote, dusty village

in the northwestern corner of Chihuahua, look to Mexico, not to the Native Americans,

for their cultural roots, but led by the renowned master artisan, Juan Quezada,

they have resurrected and now surpassed the pot-making artistry of the Casas

Grandes Puebloan tradition. According to the Fine Mexican Ceramics Art Gallery

Internet site, "Éthe potters of Mata Ortiz have imprinted in [their

ceramics] not only re-creations of [Casas Grandes] symbols, but they have searched

within their own spirit and creativity and have been able to conceive a unique

artistic language, creative and original.  They have gone through the imitation

of pre-Hispanic ceramics, and have moved on to a sophisticated creation of contemporary

art." Today several hundred Mata Ortiz potters, following Juan Quezada,

produce exceptional work that is marketed throughout the world and especially

in our desert Southwest. They have been called "the largest concentration

of artists on the face of this earth." Many collectors regard a trip to

Mata Ortiz, not as a hard drive over a rough dirt road, but rather as a pilgrimage.

They have gone through the imitation

of pre-Hispanic ceramics, and have moved on to a sophisticated creation of contemporary

art." Today several hundred Mata Ortiz potters, following Juan Quezada,

produce exceptional work that is marketed throughout the world and especially

in our desert Southwest. They have been called "the largest concentration

of artists on the face of this earth." Many collectors regard a trip to

Mata Ortiz, not as a hard drive over a rough dirt road, but rather as a pilgrimage.

Building a Collection

As you build a collection of Southwest Native American ceramics, you

can expect to pay from tens to hundreds to thousands of dollars, depending on

the quality and style of work and the reputation of the artist.

A vessel made and decorated in the traditional ways with clays, tempers, minerals and plants from natural sources typically holds a higher value, with greater potential for appreciation. While it may have a few blemishes attributable to the nature of the clay or to the process of firing, it must nevertheless embody the expression of grace in its shape, craftsmanship in its finish, and creativity and execution in its decoration. A vessel made from "greenware," that is, a vessel commercially shaped from commercial clays, may be free of blemishes, but it offers little potential for appreciation.

You will find that collecting the ceramics can lead to memorable experiences. My wife and I had a friend, an elderly man, who collected pots along with Navajo rugs (he had 34) and Native American jewelry. He allowed a beloved cat to sleep in one of his bowls, which had been crafted by a well known potter. He regretted that after the cat tipped the bowl over, knocking it to the floor, shattering it, especially after he learned that the estimated value of the bowl was several thousand dollars.

Southwest

Collectibles: Kachina Dolls

Southwest

Collectibles: Navajo Weavings

Southwestern

Arts and Crafts

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Your GPS Navigation Systems

May Get You Killed

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Desert Survival Skills

- Successful Search & Rescue Missions with Happy Endings

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert

Survival Tips for Horse and Rider

- Preparing

an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms