Sand Dunes

Phenomena of the Wind! - Part 1

by Wayne P. Armstrong

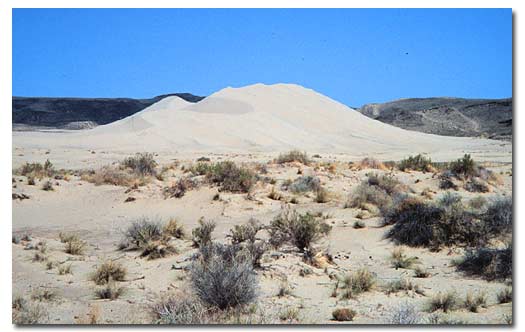

The Algodones Dunes near Interstate 8

Wind and sand create majestic dunes

that are constant but ever-changing.

They move across the deserts,

sing to the wind and

inspire our creativity!

The accumulation of windblown sand marks the beginning of one of nature's most interesting and beautiful phenomena. Sand dunes occur throughout the world, from coastal and lakeshore plains to arid desert regions. In addition to the remarkable structure and patterns of sand dunes, they also provide habitats for a variety of life that is marvelously adapted to this unique environment.

Picturesque dunes against a sky of blue or a full moon, with perfectly contoured shadows of ripples and undulating crests, have always been a favorite subject of photographers. Dunes have also been the subject of many desert movies, and have historically been a formidable barrier to vehicular and rail travel. Depending upon one's particular situation, they can be one of the most incredibly beautiful, thrilling, eerie, treacherous or just plain inhospitable places on earth.

Origin of Sand Dunes

The origin of sand dunes is very complex, but there are three essential prerequisites:

- An abundant supply of loose sand in a region generally devoid of vegetation (such as an ancient lake bed or river delta)

- A wind energy source sufficient to move the sand grains

- A topography whereby the sand particles lose their momentum and settle out. Any number of objects, such as shrubs, rocks or fence posts can obstruct the wind force causing sand to pile up in drifts and ultimately, large dunes.

There are even reports of ant hills forming the nucleus upon which sand dunes are built. The direction and velocity of winds, in addition to the local supply of sand, result in a variety of dune shapes and sizes. The wind moves individual grains along the inclined windward surface until they reach the crest and cascade down the steep leeward side or "slip face," piling up at the base and slowly encroaching on new territory. Some California dunes with crests only 30 feet high may advance 50 feet a year, posing a serious threat to nearby farms and roads.

If the wind direction is fairly uniform over the years, the dunes gradually shift in the direction of the prevailing wind. Vegetation may stabilize a dune, thus preventing its movement with the prevailing wind. Along the Oregon coast, entire forests may cover sand dune areas. Sometimes severe storms or other disturbances can destroy the forest canopy allowing sand from nearby dunes to move into the disturbed area. In fact, the author has stood at the crest of a shifting dune where the tip of a sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) was protruding from the sand.

The structure and mineral composition

of sand grains depends on the geology

of the mountains that have been

eroded away by wind and water.

The structure and mineral composition of sand grains depends on the geology of the mountains that have been eroded away by wind and water. Although most dunes are composed of quartz and feldspar grains, the brilliant snow-white dunes of White Sands, New Mexico are composed of gypsum and the spectacular black sand beaches of tropical South Pacific islands are made of fine volcanic particles.

Gleaming white sands of tropical coral beaches and atolls are composed of a glistening, microscopic assortment of reef animals and algae, including wave-worn fragments of brightly-colored corals, minute one-celled foraminiferans, fragments of sea shells and star-shaped sponge spicules. Sand grains of some tropical beaches are composed of fragments from a common calcareous green alga (Halimeda) that grows among submarine seagrass meadows and coral reefs.

Evidence of abrasion on sandblasted surfaces of telephone poles and posts reveals that sand grains seldom travel more than a few feet above the ground. Myriads of sand grains bouncing and rolling up the windward surface of a dune often form a series of ridges and troughs called wind ripples. Bouncing sand grains tend to land on the windward side of each ripple, thus producing a low ridge.

A series of ridges and troughs called wind ripples

Without getting too complicated, the spacing of ripples is related to the average distance grains jump. This in turn, is related to the wind velocity and size of the grains. Wind ripples are often very spectacular and photogenic, especially when the thousands of tiny ridges catch the shadows of early morning or late afternoon.

Bouncing sand grains tend to land

on the windward side of each ripple,

thus producing a low ridge.

Many people associate deserts with vast areas of drifting sand, as portrayed by a number of Hollywood films depicting the French Foreign Legion, battles of World War II and other dramas. In fact, less than 20 percent of the earth's total desert area is covered with sand, and sand dunes only account for about two percent of the surface of North American deserts. One of the largest dune systems in the United States is the Algodones Dunes.

It extends southeasterly for more than 40 miles (64 km), from north of Glamis in Imperial County, California to the southwestern corner of Arizona and into Sonora, Mexico. In California, the dunes range from two to six miles in width, with crests rising 200 to 300 feet (91 m) above the surrounding landscape. Other large dunes occur in Death Valley and Eureka Valley, in the Mojave Desert near Kelso, and along the California coast just south of Pismo Beach. The Eureka dunes rise to nearly 700 feet (200 m) and the Great Sand Dunes in Colorado rise to nearly 800 feet (240 m).

Algodones Dunes

Booming Dunes

For centuries, explorers and naturalists throughout the world have described strange sounds emanating from sand dunes. Strange squeaking sounds are also produced by beach sand by simply compressing the sand with your foot or poking it with a rod. Some of the earliest references about "acoustical" dunes are found in Chinese and Mideastern chronicles dating back more than 1500 years. Marco Polo described weird sounds on a journey through the Gobi Desert, and Charles Darwin mentioned it while traveling through Chile. The sounds have been variously described as singing, whistling, squeaking, roaring and booming.

Some accounts compare the sounds with distant kettle drums, artillery fire, thunder, low-flying propeller aircraft, bass violins, pipe organs and humming telegraph wires. Low frequency sounds are produced when closely packed sand grains slide over each other, such as an avalanche down the slip face of a dune. The stationary sand underneath apparently acts as a giant sounding board or amplifier to produce the enormous volume of sound. The sand must be very dry for sound production, and under a microscope the grains appear more rounded and finely polished compared with ordinary (silent) sand. Astronomers and geologists have speculated that this remarkable phenomenon may be common in the windy and nearly waterless sand dunes on Mars!

Acoustical "booming" dunes are rather widespread on earth, including the Sahara Desert, Middle East, South Africa, Chile, Baja California and the Hawaiian Islands. California has at least two documented areas with booming dunes, the massive Kelso Dunes of San Bernardino County and the scenic Eureka Dunes of Inyo County.

One of the best places to observe booming dunes in the western United States is Sand Mountain, about 16 miles southeast of Fallon, Nevada. A short dirt road north of Highway 50 leads to the base of the massive white dunes. Sand Mountain is composed of two "seif" (sword-shaped) dunes whose summits stand about 390 feet (120 m) above the desert floor. To really appreciate this acoustical phenomenon you must climb to the crest of a dune and then slide down the steep slip face. Going down with an avalanche of sand is sort of like riding down an escalator, ankle deep in sand. As the sand begins to vibrate the sound becomes quite loud, like a low-flying B-29 bomber or squadron of World War II vintage fighter planes.

Sand Mountain

There are several interesting legends about the mysterious moaning of Sand Mountain. According to Mary Holliday (Nevada Official Bicentennial Book, page 137), a large sea dinosaur or plesiosaur once lived and frolicked with its mate in ancient Lake Lahontan. Strong winds piled the lakebed sediments into what is now called Sand Mountain, completely burying the dinosaur under hundreds of feet of sand. Today the dinosaur moans for its mate and the deep blue waters of Lake Lahontan.

Where to See Booming Dunes in the U.S.

Dryness is essential for sound production in booming sand. Rain or high humidity will eliminate booming completely. Hot, dry days are best to experience this remarkable phenomenon. For more information please refer to the article about booming dunes by Jerry Schad in Omni Vol. 1, 1979: pages 131-132.

- The Kelso Dunes consist of 3 groups of large barchan (crescent-shaped) dunes, 7.5 miles (12 km) southwest of the town of Kelso in San Bernardino County. Access from either Interstate 15 or Interstate 40 is by way of the paved Kelbaker Road and a short segment of dirt road that passes within 1.2 miles (2 km) of the southern edge of the highest dune.

- Sand Mountain in western Nevada lies 2.5 miles (4 km) north of US Highway 50, about 16 miles east of Fallon. A dirt road leads to the soft apron along its base. From here it is an easy walk to the dunes.

- The Roaring Sands or Barking Sands on the west coast of Kauai, Hawaii, near Mana run parallel to the coast for a mile (1.6 km). They are unique because they consist of carbonate sand--water-worn and wind-blown fragments of shells and corals. Under a microscope (or hand lens) you can actually see the pieces of shells and corals. Most other booming dunes in the world are composed of quartz sand grains.

- Back beach dunes on the island of Niihau, Hawaii are known for their booming sounds. Beach sands along the Baja California coast may also emit squeaking sounds when shuffling through the topmost layer of sand during the dry season. This is particularly true in the Cape region.

- Booming has been reported for the Eureka Dunes in remote Eureka Valley of northeastern Inyo County, California. Highway 168 (Westgard Pass Road) heads northeast from Big Pine in California's scenic Owens Valley. About 6 miles (10 km) from Big Pine, a paved road to Eureka Valley goes to the east and north. The road turns into gravel and winds through Eureka Valley, through the Last Chance Range, and eventually connects with Ubehebe Crater in Death Valley National Monument. A bumpy dirt road at the southeast corner of Eureka Valley leads to the sand dunes. These are the tallest sand dunes in California and the home of the rare Eureka dune grass (Swallenia alexandrae) that grows no where else in the world.

Of all the Earth's natural phenomena, sand dunes are one of the most beautiful and fascinating. The complex geological factors resulting in the formation of dunes and their subsequent colonization by plants and animals are absolutely amazing. Sandstone formations, formed by ancient dunes, often reveal many mysteries about the geologic history and weather patterns of a region.

To stand before an enormous, gleaming white sand dune and realize that all of this was once an ancient lake bed or coastal plain is quite astonishing. The incredible roaring sounds of distant dunes is an unforgettable experience, particularly during the quiet hours of darkness and daybreak. Starting with the wind and tumbling particles of sand and culminating in picturesque drifts of rippled sand with an entire, dynamic, living community of plants and animals; this is one of nature's most remarkable cycles, and it is truly a phenomenon of wind.

Part 2: The Life on the Sand Dunes

References About Sand Dunes

1. Cooke, R.U. and A. Warren. 1973. Geomorphology in Deserts. Univ. of Calif. Press, Berkeley.

2. Criswell, D.R., et al. 1975. "Seismic and Acoustic Emissions of a Booming Dune." Journal of Geophysical Research 80: 4963-4973.

3. Hinds, N.E.A. 1952. Evolution of the California Landscape. California Division of Mines Bulletin 158.

4. Levin, H.L. 1981. Contemporary Physical Geology. Sanders College Publishing, Philadelphia, Pa.

5. Lindsay, J.F., D.R. Criswell, T.L. Criswell and B.S. Criswell. 1976. "Sound Producing Dune and Beach Sands." Geological Society of America Bulletin 87: 463-473.

6. Schad, J. 1979. "Explorations: Acoustic Sands." Omni 1: 131-132.

Wayne P. Armstrong is Professor of Botany

Life Sciences Deptartment - Palomar College - San Marcos, California.

He is publisher of WAYNE'S WORD®: A Newsletter of Natural History

![]()

Desert Plant & Wildflower Index

Why Owens Lake is Red

Desert Varnish & Lichen Crust

Curious Wildflower Names

Nevada's Route 50

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms