Carlsbad Caverns

Chambers of Enchantment

By Joe Zentner

Plunk. Water drops heavily onto limestone. Drip, drip, and drip. It splashes into puddles and then spreads into pools. Water lands on your nose. One less droplet to continue a cycle of a half million years, the constant creation of rock curtains and columns within Carlsbad Cavern.

The hole in the ground is the centerpiece of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, a slice of the Chihuahuan Desert in the foothills of the Guadalupe Mountains of southeastern New Mexico. The park features one of the most spectacular cave systems in the world. Of the 70+ caverns within the park, only Carlsbad, with 29 miles of underground caverns, and Slaughter Canyon’s New Cave, with three miles of caverns, are open to the general public.

How did this underground landscape develop? The chunk of limestone containing the caverns was created in Permian times, when a huge sea covered much of this part of the southwestern United States. Plants and the skeletons of sea animals combined with lime precipitated out of the seawater, and created a huge reef system. One group, the Guadalupe Mountains and the Capitan formation south of Carlsbad, is among the world’s greatest fossil reefs.

Pressure beneath the earth’s surface gradually lifted the reef above sea level, and cracks caused by this movement allowed underground water to flow through the rock. Hydrogen sulfide gas from deeper rock layers rose upward along some of the larger cracks, and, when it reached oxygen-rich water in the reef, it was converted to sulfuric acid, which dissolved the limestone. Carlsbad Cavern was thus born.

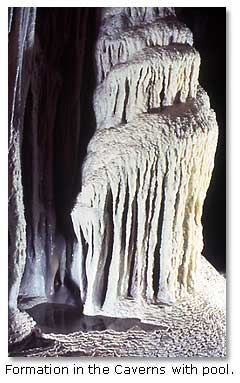

Continued uplift drained the caves, which soon filled with air. Water filtered down from the surface picking up carbon dioxide and dissolving limestone along the way. When this water reached the air in the caves, it deposited some of its dissolved minerals on the ceilings, walls and floors. The accumulation from billions of such drops created the elaborate formations that today are seen today in the Carlsbad Caverns.

Modern History

The presence of the caverns has been known by humans for probably a thousand years. Indians used the cavern mouth for shelter (their pictographs can be seen on the entrance walls), but they did not test the temper of any god of the underworld by penetrating far inside.

Carlsbad first became known locally in the late 1800s. A widely accepted account attributes the discovery to a rancher and his son searching in 1885 for a lost cow. They reported a whirlwind of bats in the sky above the desert. When the two followed the swarm to its source near the top of a limestone ridge, they found a broad cavern entrance. (Whether they ever found the cow is unknown.)

Carlsbad first became known locally in the late 1800s. A widely accepted account attributes the discovery to a rancher and his son searching in 1885 for a lost cow. They reported a whirlwind of bats in the sky above the desert. When the two followed the swarm to its source near the top of a limestone ridge, they found a broad cavern entrance. (Whether they ever found the cow is unknown.)

How cowboy Jim White found Carlsbad Cavern himself, in 1901 is a tale often told. White was surveying a fence line around dusk; when he noticed a funnel-shaped, black cloud rising above the rugged terrain. Having grown up in the desert lands of southeastern New Mexico and western Texas, he was familiar with whirlwinds clouds of dust that race across the landscape. But this “cloud” was different, and it didn’t seem to be moving over the desert.

Traveling on horseback a few miles to get a better look, White saw that the cloud was made up of whirling black specks. On closer inspection, the black specks turned out to be bats – thousands of them – spilling out of a gigantic black hole in the ground.

What White witnessed was a bat flight from Bat Cave, now part of Carlsbad Caverns National Park. For thousands of years, huge colonies of Mexican free-tailed bats have made their summer home in the cave, and from about mid-April until mid-October, hundreds of thousands of the winged creatures fly at dusk to feed on night-flying insects in the nearby Black and Pecos River valleys.

Reasoning that where there are bats, there must be bat guano, an enterprising soul named Abijah Long filed a mining claim in 1903; very soon thereafter, a guano mining operation was established in the upper reaches of the cavern. Over 100,000 tons of the rich fertilizer was mined over the next 20 years, most of it sent to southern California citrus orchards.

Amazing as the bat spectacle was, what White discovered next really bowled him over. Venturing into the hole where the bats had emerged, White entered a strange and fascinating cavern, the likes of which he’d never before seen. He found a world of gigantic stalagmites and crystalline stalactites, in rooms as big as 14 football fields. (Stalagmites rise from the cave floor. Stalactites hang from the ceiling.) White spent the last 20 years of his life exploring, building trails and leading travelers through the underground fantasyland.

Early visitors to Carlsbad Cavern had an arduous experience. Lowered to the floor of the Bat Cave in guano buckets, they climbed on crude trails over the rubble-strewn floor and down long slopes, with only lanterns to light the vast chambers through which they passed.

Eventually, the outstanding natural character of the cavern came to the attention of the U. S. General Land Office; before long, an investigation of the area was requested to ascertain the desirability of affording it national protection. In April of 1923, it was recommended that the cave be preserved as a national monument.

On October 25, 1923, President Calvin Coolidge signed a proclamation establishing Carlsbad Caverns National Monument, and making it a part of the National Park System. In 1930, an act of Congress established Carlsbad as the 28th national park. A short time later, its boundaries were extended to provide protection to other, nearby caves, which were being vandalized.

What to See and Do

The town of Carlsbad, New Mexico, makes an ideal base for expeditions to Carlsbad Cavern. The short trip from there to the cavern takes you over the northernmost reaches of the Chihuahuan Desert to the town of White’s City, the gateway to the national park.

On a clear day, you can see the peaks of the Guadalupe Mountains National Park just over the Texas border to the south, and at dusk, the sun sets in a light display worthy of an alien spacecraft landing. When you arrive at the Carlsbad Caverns Visitor Center, you can’t help but feel that you’ve come to the far edge of the earth to see this cave, and it had better be good.

On a clear day, you can see the peaks of the Guadalupe Mountains National Park just over the Texas border to the south, and at dusk, the sun sets in a light display worthy of an alien spacecraft landing. When you arrive at the Carlsbad Caverns Visitor Center, you can’t help but feel that you’ve come to the far edge of the earth to see this cave, and it had better be good.

It isn’t just good; it’s perfect, the way a cave should be. It’s the way Mark Twain pictured a cavern in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, complete with messages smoked on the wall, rock waterfalls, dripstone columns and mysterious passages.

Mammoth Cave in Kentucky is longer by over 250 miles, but what Carlsbad has to show is nonpareil cave decorations. At Carlsbad, stone sculpture lines the lighted path in amazing variety—60-foot-tall stalagmites that resemble giant bowling pins, thickets of rock icicles, limestone draperies caught for the ages in apparent midfurl, and even weirder wonders like fragile aragonite flowers and helictites that seem to defy gravity as they shoot from the cave’s ceiling, floor and walls.

The self-guided Big Room Tour is about 1.25 miles long, and takes about one and a half hours.

The subterranean Big Room is the main event. This cross-shaped chamber is 1,800 feet long, 1,100 feet wide and up to 255 feet high. Walking its perimeter is an hour’s stroll, at least. Shaped like a giant T, the Big Room is 1,800 feet long and, at its cross-section, 1,100 feet wide. You could lay the Empire State Building, with its TV tower, down in the longest part of the Big Room and still have space to spare. Here nature takes a stand against the architectural dictum that form should follow function, for this hall and its decorations seem to have been created with no purpose at all, except human wonderment.

There are also four incredible chambers in Carlsbad Caverns – the Green Lake Room, the Kings Palace, the Queens Chamber and the Papoose Room – that are, perhaps, the most impressive sights there. Relatively small chambers, they are nonetheless riotously decorated with a virtual lexicon of aptly named cave formations. Popcorn, draperies, flowstone, soda straws, and all manner of stalactites and stalagmites cram these areas, giving them an outlandish beauty. The effect is lunar, sub-aqueous, surreal. Unreal.

Bats

Each evening around sunset, between mid-summer and late October, visitors crowd the outdoor amphitheater at Carlsbad Caverns National Park. The air crackles with anticipation. Cameras are ready. Mick Jagger or Pavarotti, perhaps? Nope. It’s bats.

Taking center stage is a uniformed park ranger. He waits for the audience to settle down, clears his throat while consulting note cards, and then begins his lecture, about bats. He has hardly begun when someone in the audience yells, “Here they come!” That person could be announcing the running of the bulls in Pamplona and cause less commotion.

Taking center stage is a uniformed park ranger. He waits for the audience to settle down, clears his throat while consulting note cards, and then begins his lecture, about bats. He has hardly begun when someone in the audience yells, “Here they come!” That person could be announcing the running of the bulls in Pamplona and cause less commotion.

Out of the cave’s mouth, a single bat appears, then a few more, then dozens, and finally thousands, all swirling out of the cave and across the darkening landscape. The only sound heard is the persistent noise of the bats’ wings, a hum that mounts to a steady, droning roar.

Using echolocation – locating an object through sound waves – they catch insects on the wing; Carlsbad’s bats collectively consume more than three tons of insects per night.

If you’re really into bats (really batty?), make it a point to attend the annual Carlsbad Fabled Bat Breakfast. This annual August event (named for the guests of honor, not for the menu), induces over a thousand people to awaken early and drive to the park, in the name of eating sausages and scrambled eggs, while witnessing the spectacular homecoming of the legendary Carlsbad bats from their winter home in Mexico.

One step beyond Carlsbad on the wilderness scale, the New Cave is a relatively short but picturesque attraction in a lonely spot located near the mouth of Slaughter Canyon.

The trip to this smaller cavern requires physical stamina; not only did I have to stumble over uneven cave floor with only a flashlight for illumination, I also had to climb a very steep, very hot, path just to get there. (I am reminded of the hike down to – and up from – Crater Lake in Oregon.)

But the experience of New Cave was well worth the effort. It contains formations that surpass even those found in Carlsbad Cavern—one of them a huge column called “The Klansman,” which looks uncannily like a hunched figure in a white robe.

Should you visit New Cave, bring a strong flashlight and carry drinking water. Wear hiking boots or good walking shoes. Photography is permitted; tripods are not.

For true caving enthusiasts – those fanatics whose idea of a perfect weekend is 36 hours of crawling around the unplumbed depths of an underground wilderness – there’s Lechugilla Cave, which is longer and deeper than Carlsbad Caverns and where new passages are being discovered all the time. Access to the cave is limited to approved scientific researchers, survey and exploration teams, and NPS management-related trips.

A Fantastic World

A few hundred feet beneath the Chihuahuan Desert in Southeastern New Mexico lies a shadowy world of fantastic mineral formations—Carlsbad Caverns National Park. Carlsbad has been the setting for several movies, guano mining operations, and even, in 1979, a hostage situation. But somehow, despite all this human intervention, Carlsbad still has the charged quality of raw nature. The floodlights, the asphalt paths, the cellophane-wrapped brownies in the underground lunchroom—none of these artifacts of the human species can rob the cavern of its power to command respect.

Carlsbad will forever boggle the minds of new generations, still displaying the amazing things that nature can do with a little water, a little limestone and – by geological standards, at least – a little time. Still, when I asked my wife recently, where does “it” go when you flush a toilet 750 feet beneath the surface? She had no answer. (Actually, she said, “You’re weird.”)

If You Go

Although visitors can fly into an airport in the town of Carlsbad, 25 miles northeast of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, we chose to take the 350-mile drive from Albuquerque, across the arid plains of eastern New Mexico. Above, the clouds have weight and biblical billow; at rare rest stops, rattlesnake warnings are posted, and, occasionally, an Amtrak train roars by.

To get to Carlsbad Caverns from Carlsbad, New Mexico, travel 27 miles south of U.S. 62/180 and State Route 7. The Visitor Center is open 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. during the summer, and 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. during the spring. For additional information, contact Carlsbad Caverns National Park, 3225 National Parks Highway, Carlsbad, New Mexico, 88220 (Phone 1-505-785-2232).

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms