New Mexico’s Organ Mountains

Explore the Organ Mountains Trails

by Jay W. Sharp

The Organ Mountains, a small and rugged 9,000-foot high, 32 million-year-old range in south-central New Mexico just east of Las Cruces, have long drawn the adventurous into the rocky folds and crevices of their steep granitic and rhyolite slopes. The mountains hold evidence of their attraction for humans in secluded caves, Indian rock art, abandoned mines and crumbling ruins. Clues to prehistoric hunters and farmers, Apache raiders, treasure hunters, miners, gunfighters, revolutionaries, Union and Confederate troops, hermits, ranchers, and early tourists are scattered in a multitude of sites across the range.

Chihuahuan Desert Island

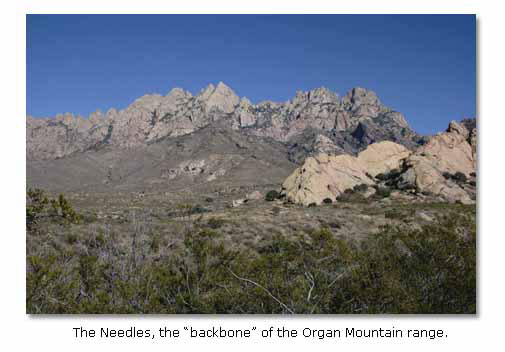

Unlike their stratified neighboring mountain ranges, which had origins in ancient and placid seas, the Organs emerged from the molten interior of the earth in a complex sequence of violent magmatic eruptions, lava flows, structural warping and fracturing, and relentless erosion. Rising like an island for a mile above the surrounding Chihuahuan Desert floor, the Organ Mountains now stand as “one of the most picturesque and rugged mountain ranges in the Southwest,” said New Mexico Institute of Mining & Technology’s W. R. Seager in his Memoir 36 – Geology of Organ Mountains and Southern San Andres Mountains, New Mexico. “The row of jutting, fluted, bare-rock pinnacles known as the Needles – the backbone of the range – can be seen on a favorable day from nearly 100 miles away... The stark, sawtooth profile, their challenging slopes and changing moods have made the Needles a favorite of artists, photographers, and mountain climbers...” The mountains derived their original name, Sierra de los Organos, from the early Spanish, who thought the pinnacles resembled the pipes of the great organs in the cathedrals of Europe.

Rugged as they are, the Organs serve as a haven for one of the most diverse plant and wildlife communities in the Southwest.

The mountains harbor more than 800 plant species, including mesquite trees, creosote bushes, lecheguilla agave, and several acacias and gramma grasses in the lower flanks; various juniper and oaks in the intermediate elevations; and ponderosa pine, mountain mahogany and various juniper and oaks in the higher elevations. Several plants, for instance, the Organ Mountain evening primrose and the Organ Mountain pincushion cactus, occur nowhere else. They have perhaps the richest assemblage of ferns, mosses and lichens in the West. With sufficient rainfall during the late summer monsoon season, the lower slopes blaze golden with Mexican poppies in the following spring, especially at the northern end of the range.

The Organs, enriched by several permanent springs and various intermittent streams, host some 80 species of mammals, ranging from the Organ Mountain Colorado chipmunk to the mule deer; 185 species of birds, ranging from the ruby-throated hummingbird to the golden eagle; and 60 species of reptiles and amphibians, from the horned lizard to the western diamondback rattlesnake to various toads.

Dripping Springs Trail Complex

You might begin your exploration of the Organs – a National Recreation Area administered by the Bureau of Land Management – at the Dripping Springs trail complex, located at the A. B. Cox Visitor Center, 10 miles east of the Interstate Highway 25 University Exit, at the end of Dripping Springs Road. The center was once the home of the A. B. Cox family, well known ranchers on the western side of the Organ Mountains.

In the visitor center you will find a contour map, which will give you an overview of the mountain range. You will find small exhibits of prehistoric and historic artifacts and an especially interesting collection of local historic photographs. Just outside the center, you will find a native plant garden, with a variety of Chihuahuan Desert species, including the Organ Mountains evening primrose and the Organ Mountains pincushion cactus.

You will discover the head of the Dripping Springs Trail, perhaps the most popular in the Organs, immediately south of the visitor center. A generally uphill, mile-and-a-half-long trudge, it leads past the permanent Dripping Springs to the ruins of what was surely one of the Southwest’s most secluded and exotic hideaways, Colonel Eugene Van Patten’s Dripping Springs Resort. Van Patten – nephew of the famed John Butterfield, employee of his uncle’s stagecoach operation, veteran Confederate officer of the Civil War Glorietta Pass battle (east of Santa Fe) and husband of a Piro Indian woman – built his resort in an isolated and sequestered mountain alcove in the 1870s. He employed Indians who lived in quarters on the site, carried water in handmade ollas (large clay jars) and performed their native dances for the guests. At his 16 rooms, dining room and ballroom, at the foot of a precipitous mountain face, he hosted famous Southwestern personalities such as Pancho Villa, who became legendary in Mexico’s early 20th century revolution, and Pat Garrett, who shot Billy the Kid at New Mexico’s Fort Sumner.

The trail also leads past the ruins of the home of Dr. Nathan Boyd, who bought the Dripping Springs Resort and then homesteaded nearby in 1917. Married to an Australian woman who had contracted tuberculosis, Boyd converted the resort from a cheerful retreat for the famous into a gloomy and isolated sanatorium for the ailing. Eventually he sold it to another physician, who continued to care for tubercular patients at the site until its abandonment in the first half of the 20th century. Today the ruins of the buildings, including a coach stop for the resort guests, lie along the upper end of the trail.

Just east of the A. B. Cox Visitor Center, you will find the Crawford Trail, a mile-long pathway that will conduct you northward, through a plant community with a number of localized and unusual species, to the Fillmore Trail. You can follow the Fillmore Trail eastward, over a rocky surface, into the narrowing walls of a box canyon and – with some rain and good luck – to the rush of a waterfall. Just at the mouth of the canyon, you will pass the site of the concentrating mill for the Modoc Mining Company, which took galena (lead and silver) ore from some 13 mines. Nearby, mostly on private property, lie other remnants of the mining operation—a place where dreams eventually turned to dust and stone.

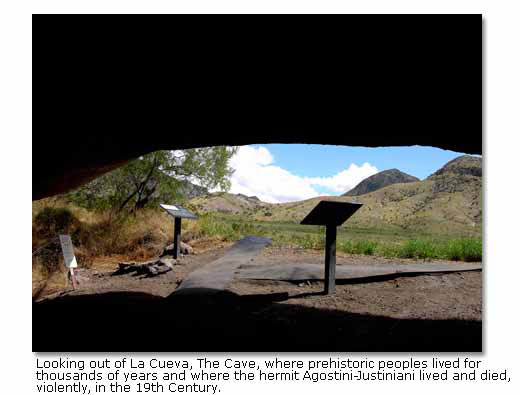

On the Dripping Springs Road, a half mile west of the visitor center, you come to the turnoff to the La Cueva Picnic Area and the La Cueva Trail beginning. A half-mile hike along the south side of a tuff (consolidated volcanic ash) outcrop will take you to La Cueva, the Cave. With a ceiling blackened by the smoke from 7,000 years of campfires, La Cueva, although it is small, has yielded 100,000 artifacts to the trowels, shovels and screens of archaeologists. It sheltered bands of hunting and gathering peoples, who subsisted primarily on bighorn sheep, pronghorn antelope, mule deer, blacktail jackrabbits and desert cottontails for more than 5000 years, and then extended families of farming peoples, who raised corn, beans and squash and hunted the local wildlife. It still has mortar holes in nearby bedrock, where Indian women once used stone pestles to pound and grind seeds into flour.

In the 1860s, La Cueva served as home for a hermit, Agostini-Justiniani, a strange man who had descended from Italian nobility, according to BLM information at the visitor center. Although he likely trained as a priest, Agostini allied himself with Los Hermanos Penitentes, or the Penitent Brothers, who scourged themselves in bloody religious rituals. He would become revered as a healer by the Penitentes. After wandering across much of Europe, Latin America and the United States, he wound up as an aging man near Dripping Springs, taking up his lonely desert residence, perhaps in the spirit of John the Baptist, at La Cueva.

On the isolated flanks of the Organs, he continued with his prayers and his healing of the sick. Warned of the danger of living alone in the remote area, he promised residents in the valley to the west “to make a fire in front of my cave every Friday evening while I shall be alive. If the fire fails to appear, it will be because I have been killed.” He would prove to be prophetic. In the spring of 1869, his Friday night signal fire failed to appear. When found the following morning, he lay dead, a knife in his back, a penitential “metal girdle full of spikes” around his loins.

Soledad and Bar Canyon Trail

Taking Dripping Springs Road west from the visitor center for about five miles, you will come to the intersection with Soledad Canyon Road, which leads south for a mile then east, to the southern end of the Organ Mountains. There you will find the head of the Soledad and Bar Canyon Trail, a rising and falling loop of about three miles through a natural amphitheater near the juncture of the two canyons. Located on a land parcel added to the Organ Mountain National Recreation Area through a cooperative effort by a private landowner, the Nature Conservancy of New Mexico, the BLM and one of New Mexico's longest serving congressmen, Joe Skeen, the trail leads through a rich mountain plant community. It conveys a feeling of the loneliness and isolation of the early Organ Mountain ranchers, especially through the ruins of a small rock home of an unknown owner at the northern end of the loop.

The Other Side of the Mountain

You can explore the eastern side of the Organs from the Aguirre Springs National Recreation Area, where you can camp in designated sites among juniper and oak trees and hike through dramatic vistas on the Pine Tree and Baylor Pass trails. Aguirre Springs lies about 14 miles east of the Interstate Highway 25 Main Street Exit, off U. S. Highway 70/82.

Enroute from the west, you will pass through the historic San Augustin Pass, between the Organs on your right and the San Andres Mountains on your left. As you approach the pass, you will see a marker that identifies the site where, on February 29, 1908, a cowboy named Wayne Brazel – or someone – shot Pat Garrett in the back of the head. Brazel claimed self-defense. He won acquittal in a trial in which jury deliberations took no more than 15 minutes, said C. L. Sonnichsen in his Tularosa: Last of the Frontier West. You will also pass through the village of Organ, which served as the center of gravity for mining operations in the Organ Mountains during the late 19th century. In the slopes overlooking the village, you can still see the tailings of several of the mines, which altogether produced some millions of dollars in lead, copper and silver ore.

A mile or so east of San Augustin Pass, you come to the turnoff to Aguirre Springs, six miles to the south, and the trailheads for both the Pine Tree and the Baylor Pass trails.

The 4.5-mile-long Pine Tree Trail, which makes a loop through the eastern flanks of the Organs, begins at an elevation of about 5,600 feet and ascends to nearly 7,000 feet then returns to 5,600 feet. In your hike, you will leave the mesquite trees and creosote bushes behind. You will pass alligator junipers that grow from seemingly impossible rocky matrices in an example of the tenacity of life. You will reach ponderosa pines at the higher elevations, from where you can look eastward, down into the Tularosa Basin and see the blinding dunes of the White Sands National Monument. You can look beyond the basin and, on a clear day, see the Sacramento Mountains and Sierra Blanca, a 12,000-foot-high peak that the Mescalero Apaches hold sacred. You can see, a mile southeast of the main Organ Mountain range, Sugarloaf Peak, an incongruously conical, stony pinnacle some 8000 feet in elevation. From the primal folds and crevices of the granitic slopes of Pine Tree Trail, you can see, on the desert floor below you, the launch pads of the White Sands Missile Range, the birthplace of high tech weaponry and America’s space program.

The 6-mile-long Baylor Pass Trail, the only maintained footpath across the Organ Mountain range, begins at an elevation of about 5,540 feet at Aguirre Springs. It ascends to 6,430 feet at Baylor Pass, where you can see the Tularosa Basin to the east and the Rio Grande Valley to the west. It then descends to 4,865 feet, down the western side, to a trailhead just off Baylor Canyon Road, which parallels the Organs on the west side. You can, of course, hike the trail east to west or west to east. On the trail, you will be walking in the steps of Confederate Lieutenant Colonel John Robert Baylor, who led the Texas Mounted Volunteer regiment on a mission of high drama and low comedy in the summer of 1861. The colonel, with a force of about 200, had set off in pursuit of a Union force of about 500 troopers, who were retreating from a potential Confederate assault on their ill-equipped and poorly supplied fort in south central New Mexico. Baylor followed the trail now named for him eastward, across the Organs. On the eastern side, he turned north, paralleling the range to San Augustin Pass, where he intercepted the Yankees. Anticipating a hard and bloody fight against a force two and a half times larger than his own, Baylor must have been stunned when the entire Union force promptly gave up without firing a shot. He soon learned why. The Yankees had – at least according to knowing whispers – filled their canteens, not with water for the hot summer march across the Chihuahuan Desert, but with whiskey. They arrived at San Augustin Pass dehydrated and drunk, quite happy to surrender in return for water.

Other Organ Mountain Adventures

In addition to exploring the trails of the Organ Mountains, you can – provided you are exceptionally fit and skilled – climb the various peaks of the range. “The range,” said Herbert E. Ungnade in Guide to the New Mexico Mountains, “consists of an amazing number of spires and pinnacles which lie on the 20-mile ridge between San Augustin Peak at the north end and Rattlesnake Ridge...” at the south end.

“Climbing in the Organs is rather different from other mountains in New Mexico. It is necessary to carry water. One must learn to avoid the ever-present cactus, thornbush, and yucca, and climbers frequently clap hands to induce rattlesnakes to rattle so that they may be avoided. Loose rock hazard is present on most routes... Once climbers have become used to these hazards which the Organs present, they seem to be drawn back irresistibly to this fascinating array of needles, towers, walls, and buttresses.”

The Organ Mountains do seem to cast a spell. “One does not forget the Organs blackening against the sunset, swathed in a veil of lilac shadows...” said Sonnichsen.

For more information and maps, contact:

U. S. Department of the Interior

Bureau of Land Management

Las Cruces Field Office

1800 Marquess Street

Las Cruces, New Mexico 88005

Ph: 1-505-525-4300

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms