Albert Jennings Fountain

The infamous Fountain Murders

By Jay W. Sharp

As he harnessed his team of two horses to his four-wheel buckboard carriage, Albert Jennings Fountain understood fully the threat that he – with his eight-year-old son, Henry – would face in crossing the Tularosa, that foreboding desert basin in south-central New Mexico.

Even though his carriage bore a cover, which offered some protection against the icy winds of winter blowing over the land, Fountain also worried about young Henry, who was suffering from the onset of a bad cold. The child needed his mother’s caring hand.

Fountain and his young son faced a three- to four-day westbound journey, some 140 miles in length. It began in Lincoln, nestled in the pass between El Capitan Mountains to the north and Sacramento Mountains to the south. It led southwest, through the Ponderosa pines of the Sacramentos to the village of Tularosa. From there, it turned south to the hamlet of La Luz. It then bore southwest for 40 miles southwest across the basin, a desert grass- and shrubland, past the spectacular dunes called White Sands and a gypsum-laced rise called Chalk Hill. It ascended San Augustine Pass, between the Organ and San Augustine Mountains, then descended the western flanks of the mountains, passing through the mining community of Organ. As it drew near the Rio Grande river valley, it passed through Las Cruces and into Mesilla and home.

A Hard and Lawless Land

If Fountain knew the risk before him and his son, he also bore the confidence of a man who had flourished in a land as hard as carborundum. He saw in southern New Mexico and western Texas an often lawless country that, in that late January of 1896, still bore the open wounds of the Mexican/American and Civil Wars. Americans, moving westward, appropriated lands that rightfully belonged to Hispanic peoples who had not met the bureaucratic requirements necessary to validate their claims under U. S. law. Newly minted land barons effectively subjected Hispanic peoples to a system of peonage. The Catholic bishops of Durango and Santa Fe had, until recently, competed for the allegiance of the Faithful. Bitter Republican and Democratic political rivalries grew out of the desert sands, giving rise to a bloody riot on the plaza of Mesilla in 1871. Cold-blooded and cunning attorneys, newly arrived Texas ranchers, audacious cattle rustlers and callous gunfighters formed alliances of convenience, a wellspring of enemies for any man they didn’t like.

The Enemies He Makes

Albert Jennings Fountain knew his enemies well. He knew that Las Cruces lawyer and political rival Albert B. Fall and Tularosa Basin cattleman Oliver Lee and gunmen like Billy McNew and Jim Gilliland stood at the top of the list of those who would like to kill him, given the chance.

Fall, a “rough-hewn native of Kentucky and son of a Confederate office,” according to Gordon R. Owens, The Two Alberts: Fountain and Fall, had held a kaleidoscope of odd jobs, including that of a miner in the Mexican state of Zacatecas. He grew fluent in Spanish. He read the books of the law. He married. He moved with his family to southern New Mexico in 1887 to capitalize on post-war opportunities, becoming a powerful force in the Democratic Party. Fired by a towering ambition that would propel him to regional and national prominence, Fall soon became the crafty leader and lawyer for the equally ambitious Lee and his hired gunfighters. He hated Albert J. Fountain, finding him “‘exceedingly obnoxious to myself,’” according to a quote cited by A. M. Gibson in The Life and Death of Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain.

Lee, “magnificently muscled, straight as a young pine, catlike in his coordination,” according to C. L. Sonnichsen in Tularosa: Last of the Frontier West, had come from Texas to the basin as a young man with his family to claim a ranch and raise cattle. He soon became famous because of “his wizardry with a six-shooter and rifle.” He killed men who challenged or crossed him. He helped himself to the cattle of major livestock syndicates. In return for the legal services of Fall, Lee and his men terrorized men and voters on the lawyer’s behalf.

Sometime in the early 1890s, Lee “added Bill McNew and Jim Gilliland to his inner circle” said Sonnichsen. “McNew, a tough Texan with ice-blue eyes, had come down from the mountains to work for Lee.” Gilliland was “another hard-fighting, iron-nerved Texan... He wanted to prove that he was not afraid of anything, however, and that makes a man dangerous.”

Like other private ranchers in the region, Lee and his men – their crimes absolved in the courts by Albert Fall – felt entitled to government and private land in the Tularosa and the cattle of the big companies. In a practice called “brand blotting,” Lee and his men altered brands on other people’s cattle, modifying the identifying marks so they would resemble his own. Bloody conflicts spiraled into a full-scaled range war, yielding bitterness that lingered among local families well into the 20th century.

Fountain Takes His Toll

Even knowing the risks, Fountain challenged Fall and his cohorts in the political arena and in the courts. He came to the task well seasoned and thoroughly prepared. The son of a sea captain, he had traveled throughout the world. He had worked as a miner and a freighter. He had studied the law. He had joined the Union’s First California Infantry Volunteers, commanded by Colonel James H. Carleton, and marched eastward across the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts to southern New Mexico and western Texas. He had advanced rapidly from private to lieutenant. He had fought the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apaches in the Indian Wars. Married to an Hispanic woman, Mariana Pérez, he had become fluent in Spanish.

In 1866, he moved with his family to El Paso, where he established a legal and political career, held various local offices, and won state office. No stranger to violence, he “killed political enemy Frank Williams in a duel after Williams insulted him in a saloon,” said Gibson in an article, “Fountain, Albert Jennings (1838 – 1896),” The Handbook of Texas Online.

In 1873, fearing for the safety of his family in El Paso, he moved to Mesilla, where he carved out a new legal and political career. He promptly became a powerful force in the Republican Party, serving in leadership roles in the territorial legislature. He founded a local newspaper. He helped lay the foundation for the local university. He served as Colonel in the Mesilla Scouts, a volunteer militia charged with protecting the community against raids by the Apaches. As one of the most prominent attorneys in the state, Fountain became known, not only for his defense of Billy the Kid, but even more for his aggressiveness as a prosecutor. He stood as the most powerful political threat against Fall and as the most serious legal threat against Lee and other rustlers. He was about to turn up the heat even more.

As chief investigator and prosecutor for the newly formed Southeastern New Mexico Stock Growers’ Association – an organization of the big cattle operators backed by eastern and foreign capital, according to Gibson – Fountain set out, both in the legislative and law-enforcement venues, to put a stop to the cattle rustling. The thievery had cost the association members thousands of head of livestock. “By late July [1894],” said Gibson in The Life and Death of Colonel William Jennings Fountain, “scarcely three months after the organization of the southeastern New Mexico Stock Growers’ Association, warrants were issued for the arrest of the Slick Miller gang,” a band of cattle rustlers out of central New Mexico. Within a year, Fountain had engineered convictions that sent 15 of the gang to prison.

He turned next to Oliver Lee. “I shall start in person for Tularosa and begin the work of corralling the entire gang” Fountain said in a report to the Association, according to Gibson. “The present condition of affairs cannot long exist I anticipate a hard contest, one perhaps to the death.” His wife, Mariana, mourning the recent death of her mother, now suffered “from mental trouble arising from her apprehension that my life is in danger.”

A Feeling of Being Closely Watched

Fountain, with a thrilled young Henry at his side (no one, insisted Mariana, could be evil enough to attack a child), had come to Lincoln in that January of 1896 to seek indictments against Oliver Lee and his men. He presented a grand jury in the Lincoln County Courthouse with a case full of evidence, including depositions, letters, affidavits and brand registrations document, according to Gibson. Always persuasive, Fountain secured 32 indictments.

“Throughout the proceedings,” said Gibson, “Fountain had the feeling of being closely watched—in the courtroom, on the streets of Lincoln, and in the hotel lobby at night as he visited with friends. During a recess on the final day of court an anonymous messenger handed him a crudely written note. It warned, ‘If you drop this we will be your friends. If you go on with it you will never reach home alive.’”

In the afternoon of January 30, Fountain loaded the buckboard and started for home, with Henry at his side. On the first leg of the trip, they headed up into the Sacramento Mountains, through the Ponderosa Pines, stopping for the night near the village of Mescalero, where an Apache friend gave them a pinto pony.

The next morning, January 31, with the pinto tied to the rear of the buckboard, they headed down the western slope of the Sacramentos to the desert floor. At Tularosa, at the foot of the mountains, they turned south, skirting the western flank of the mountains, headed for the hamlet of La Luz to spend the night. He stopped for brief visits with friends he met along the way. During the day, he noticed two riders, sometimes ahead, sometimes behind, always too far away to permit recognition. Fountain, perhaps remembering the note, “you will never reach home alive,” grew uneasy.

At La Luz, Fountain gave Henry, now taken with his bad cold, a quarter to buy sweets. The child spent 10 cents. Carefully, he tied the change, a nickel and a dime, in the corner of his handkerchief.

Early the next morning, February 1, Fountain, with Henry beside him and the pinto pony in tow, struck the wagon road to the southwest, across the Tularosa Basin past White Sands, bound for Mesilla and home. He met a stagecoach. The driver, Santos Alvarado, said that he had seen three riders back up the road. They stayed too far away to permit recognition. Soon Fountain saw the three riders, one, he noticed, on a white horse.

After a rest at a mid-way stage stop, Fountain pressed on. He met another stagecoach. As they stopped for a brief visit, he and the driver, Saturnino Barela, both saw the three riders, hovering like specters in the distance. Fountain declined Barela’s suggestion to return to the mid-way stage stop, spend the night, then finish his journey in the company of a stage the following day. Henry had a cold. He needed care. Mariana, worried, expected them home sooner. Besides, no one could be evil enough to attack a child.

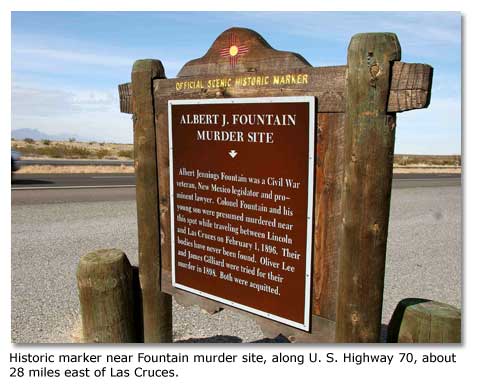

He headed across the rise called Chalk Hill. With the sun falling and a cold wind rising, Fountain gathered a blanket and a quilt around Henry, said Gibson. He buttoned his heavy overcoat. He looked for the three riders. He could not see them. With growing uneasiness, he picked up his Winchester rifle. He heard the sudden crack of gunfire. That was the last thing that he or his eight-year-old son would ever hear. Someone was evil enough to attack a child.

The Aftermath

The next morning, an anxious Saturnino Barela, at the Chalk Hill crossing on his return trip to Las Cruces and Mesilla, discovered the tracks of Fountain’s waylaid buckboard. He found the hoof prints of strange horses. He saw no sign of the carriage, the horses, or Fountain and his son. He rushed across San Augustine Pass and down the mountain slope to Fountain’s home in Mesilla to alert the family.

Two search parties, one of them led by Fountain’s son, rushed through the darkness of the icy night to the murder site. Helped by two Mescalero Apache scouts, they began piecing together the evidence as the sun rose over the Sacramento Mountains, on the eastern horizon. They found where a man had knelt and fired from behind a growth of shrubs, leaving shell casings on the ground. They discovered the site where two men had tended three horses. They followed wagon tracks and discovered a pool of blood. One man discovered a blood-soaked handkerchief with a nickel and a dime tied carefully in its corner. They followed the wagon tracks of the buckboard and the hoof tracks of six horses east for some 12 miles, into sand dunes west of a small and isolated mountain range called the Jarillas. There, they discovered the carriage, which had been plundered and abandoned. They tried to follow the tracks of the killers. One trail led toward one of Oliver Lee’s ranches, where trackers found a threatening reception.

In the days to come, new posses joined the search, hoping the find the bodies of Fountain and his son. Rumors swirled throughout the desert and across the country. Newspapers covered the story in detail. The governor of New Mexico offered a reward for the capture of the killers. The Republican Party and the regional cattlemen mourned Fountain’s passing.

According to Sonnichsen, a local paper, the Republican, said, under the headline THE HOUR AT HAND: “A devoted wife and loving family await longingly and hopefully the coming of a kind husband and father and a dutiful son and brother upon whose living faces they may never look again. Many friends hope against fate for the return of an honored friend while many other search the plains for his living or dead body. If dead there can be no question as to at whose door the blame lies...”

Meanwhile, Albert Fall, said Gibson, “screamed that the whole deal was political; that the Republicans were using the Fountain issue to crucify innocent Democrats.”

Gradually, as months and then years passed, investigators, including Pat Garrett, famous lawman and gunfighter, finally put together a case. The governor, said Gibson, told a representative of the famous Pinkerton National Detective Agency that, “The men who are suspected of this crime are Oliver Lee, William McNew, and James Gilliland.” They eventually came under arrest. In a legal charade orchestrated by Albert Fall, McNew won his release. Lee and Gilliland, defended in their trial by Fall, won “Not Guilty” verdicts. “The gallery,” said Gibson, “cheered wildly.”

Although rumors and leads surfaced for years, no one has ever found the bodies of Fountain and his son.

Politically craven, Albert Fall switched from the Democratic Party to the dominant Republican Party in 1904. He won a seat in the senate when New Mexico became the country’s 47th state in 1912. He served until 1921, when he accepted President Warren G. Harding’s appointment as Secretary of the Interior. He promptly proceeded to engineer the infamous Teapot Dome scandal, which prompted his resignation from office, his conviction on a felony charge, a term in prison and the loss of many assets. Disgraced, he moved to El Paso, where he died in 1944.

If you would like to learn more about the infamous Fountain murders, you can get a good overview of Fountain and Fall in the internet sites Borderlands and The Handbook of Texas Online. You will discover good accounts of the murders in A. M. Gibson’s The Life and Death of Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain; Gordon R. Owen’s The Two Alberts: Fountain and Fall; and C. L. Sonnichsen’s Tularosa: Last of the Frontier West. You will find good background information in Owen’s Las Cruces, New Mexico 1849-1999: Multicultural Crossroads and Mary Daniels Taylor’s A Place as Wild as the West Ever Was: Mesilla, New Mexico 1848-1872.

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms