Oasis Hunting

Joshua Tree National Park

by Ryan Weaver

I had a simple goal: hike to every oasis in Joshua Tree National Park.

I would do it alone. It wasn’t that I desired solitude. It’s just that nobody wanted to come with me. It was, potentially, going to be an arduous vacation.

By the time I pulled into the Cottonwood Visitor Center I knew that, according to the National Park Service’s website, out of 158 desert fan palm oases in North America, Joshua Tree claims all of five. Five oases in a million acres. And yet I was having trouble finding facts about these oases—namely, what they were called and where they could be found.

The Five(?) Oases

With the help of knowledgeable ranger Jenny Arismendi, we pinpointed Oases Cottonwood Spring, Lost Palms, Mara and 49 Palms on the tourist map. Although all trails seemingly ended at Lost Palms, both of us knew the fifth oasis, Victory Palms, lay somewhere ahead.

Arismendi unfurled a lavish topographic map and opened On Foot in Joshua Tree National Park to page 144 without bothering to consult the index, which suggested that she’d spent many a lonely hour at her post. Using the book and map together, we saw that traveling a mile beyond Lost Palms would bring one to Victory Palms.

We also saw a surprise: one paragraph about Munsen Canyon. “With over 110 palms,” the book said, “this canyon easily surpasses Lost Palms canyon for the most palms in one canyon.”

A sixth oasis in Joshua Tree! Why not mention Munsen in park literature or on the Internet? Why let the largest oasis cower in obscurity while lesser oases wallowed in fame?

Apparently, because to tempt people to go there would be to put people in danger. Rated as “Difficult +”, a 12-mile round trip, “strenuous and difficult,” it was arguably the harshest destination-hike in Joshua Tree. The more one considered it, the more it seemed that Munsen was only possible to reach if one was a bighorn sheep.

Cottonwood Spring Oasis

Cottonwood isn’t disappointing, but it isn’t exactly a hoot, either. The whole oasis consists of about two-dozen palms and one huge cottonwood sprouting in a dense clump. Although the shady interior of this mini-jungle is inviting, it’s protected from reckless boots by a split-rail fence arranged in a semi-circle. Extending from under the fence is a swatch of trampled mud—the remains of a spring that once gushed 30,000 gallons a day.

Placards reveal that while the spring is ancient, the trees were planted between 1890 and 1910 by freight-haulers and prospectors. Cottonwood, then, wasn’t a vision of a genuine fan palm oasis as much as an abandoned, overgrown garden.

Nearby, I saw another split rail fence. This one was arranged in a circle around what appeared to be the loose stones of an old campfire ring with a few of the rusted tin cans that one associates with the mining-era strewn about. A placard suggested, rather optimistically, that this was an old mule-driven arrastra, that is, a pit where ore was crushed.

I stood there laughing until I noticed a trail meandering up into the barren hills. At the end of that trail lay Lost Palms Oasis.

Lost Palms Oasis

Since one cannot reasonably hope to hike the seven miles roundtrip to Lost Palms in one day without encountering some oppressive hour of desert heat, it seemed a good idea to backpack in around dusk and spend the night.

In order to backpack in Joshua Tree National Park, one simply needs to sign into a backcountry board in the parking lot at the trailhead. It’s free and painless. For me it was also comforting, because I was alone and a ranger checks on parked vehicles every night. If I wound up bitten by a rattler or shriveled with dehydration or half-crushed under a boulder and was a week late in getting back, I assumed it would be this ranger who would scratch his head and say hmmmmm.

The trail to Lost Palms Oasis is raw. Footprints alone delineate it, although an occasional 4X4 post with an arrow provides reassurance. Many times I found myself looking around blankly at a jumble of footprints that took off in all directions like the game trails that flank mountainsides. Eventually I realized that the best one can do is follow the direction of the footprints and hope that some joker hadn’t turned the posts to send one careening all over creation.

Fortunately, backpackers are mostly a responsible herd. There was zero litter on the trail, and it was a good hike. I startled lizards and rabbits from their shady retreats. The Salton Sea blazed in the distance. And then, in the steep canyon, two bursts of green.

As hiking literature I’d brought along The Alchemist, because it’s light to carry and because in it the desert is a place to chase dreams. I’d just read this passage: “He always enjoyed seeing the happiness that the travelers experienced when, after weeks of yellow sand and blue sky, they first saw the green of the date palms. Maybe God created the desert so that man could appreciate the date trees, he thought.”

Looking down on the foliage of Lost Palms Oasis and Dike Springs, I agreed.

I hiked in at first light and discovered that the pictures I’d drooled over on the internet were outdated. The gorgeous reflective puddles settled serenely amidst the palms had been reduced by drought to a colony of reeds.

Getting to Dike Springs, which is in a side canyon, required an acrobatic feat of bouldering. The palms form a compact circle, the center carpeted by discarded fronds. The shade was unbroken. There was no split-rail fence. I waltzed right in and lay down, soaking it all up, watching the birds, listening to the fronds flutter.

The Lost Palms are scattered along a dry bed of boulders that meander downhill. I wandered among them. Soon, I found myself standing on a precipice with an endless view of the baked Colorado Desert, and I understood why the trail stops here on the maps. There is no trail to Victory Palms. There is only a plunging of boulders.

Victory Palms

In leaping down to Victory Palms, you parallel a rotted, rusted pipe. This pipe is fascinating because each astoundingly heavy 20-foot section had to be hauled up here and put together by some poor bastard who must have been very bad in a past life.

Follow the rotted pipe road, I chanted. Follow the rotted pipe road.

Victory Palms came into view long before I reached them. They were in the last wedge of canyon before the boulders were swallowed by the giant sand wash that swung around an arroyo and filtered toward distant Highway 10.

I was gratified to see that what the guidebook had said about there only being two palms was incorrect. In addition to two older palms were four younger ones. Fresh life. Perhaps one day this would be a nice oasis indeed, but standing among Victory Palms just then didn’t inspire me to linger. They were too distantly spaced from one another to produce even a little decent shade, and it was noon. I required shade or movement.

I scrambled up mountains on the north and south in search of Munsen Canyon. I’d failed to purchase the topographic map and was running off memory, which I was sure would suffice. I was wrong.

Munsen eluded me, and eventually I realized that I’d be too tired to explore the canyon even if I did find it. So I scaled the boulders back up into Lost Palms and stumbled back over the rough trail to Cottonwood Springs, where a mattress in the bed of my truck awaited me.

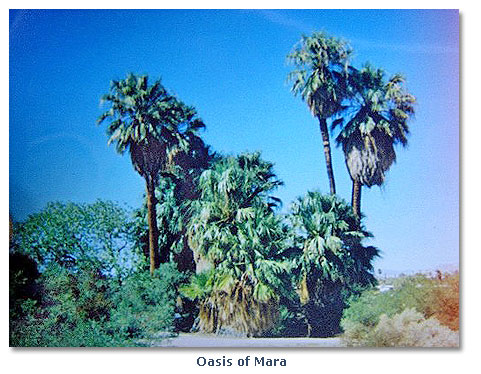

Oasis of Mara

Time to rest. I drove leisurely up through the park to the North Entrance, where another visitor center and the Oasis of Mara were located.

The visitor center was nice; the oasis was melancholy. It wasn’t in a canyon, which suggested it was manmade like Cottonwood. And it was, but at least this time the story was interesting. Legend holds that Indian women who desired male offspring came to this spring on the advice of their medicine man. He instructed them to plant a palm for each male born, and 29 palms soon sank shallow, dense roots into the topsoil.

A patch of vegetation surrounds the palms, forming an alluring area again protected by a split-rail fence. This is necessary, of course, but a thing can be necessary and regrettable too. There are a few iron and plastic benches cemented into the shade nearby so that some of the area’s peace can be savored. The half-mile stroll around the greenery is freshly paved and clean, complete with little placards bursting with information.

One such placard states that the Serrano Indians called this place “Mara,” meaning “little springs and much grass.” It says that gold-hunters, cattleman and homesteaders came and displaced the Indians. They stayed and by the 1940’s, the spring water no longer bubbled to the surface.

There’s a panoramic view from this placard of the dusty city of 29 Palms. It’s a rather ugly scene of urbanization, and easy to resent. Every building does its part to lower the water table. The National Park Service is now forced to pump in water so that the plants and animals of the oasis can survive.

Mara is a nostalgic place; it’s easy to pine for the past and lament the present here.

49 Palms

This was to be my favorite oasis. It was foreshadowed when I asked someone in 29 Palms how to get there, and she said, “I believe it’s the left by the vet clinic.”

She was right. Sighting the High Desert Animal Hospital is your best bet, since there are no signs anywhere, concerning anything.

The hike runs three miles round-trip, but it’s worth the customary elevation gain and loss as one traverses mountains because even from a distance 49 Palms is the most beautiful.

Not so dense as the other oases but rather luxuriously thick, 49 Palms has the superior feel of a forest. There’s ample room to take a stroll, to relax on cool polished boulders, to contemplate the puddles and ponds and to envision how this place must flow in wet times – waterfalls everywhere – and all of this under a canopy of perfect shade. This is the best oasis for families, for lovers, for picnics, for inspiration, for rejuvenation. Good thing that I enjoy lingering by myself. I was the only one there.

At this point in my journey I needed this rejuvenation of both body and spirit. For I had decided not to let Munsen Canyon escape me.

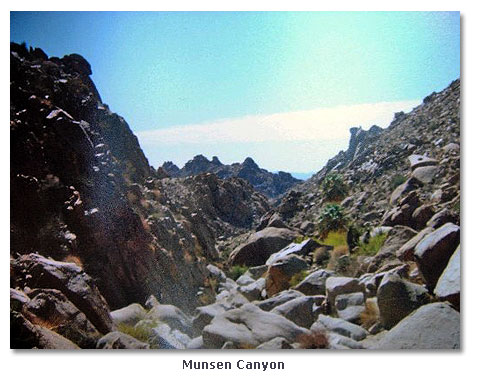

Munsen Canyon

After surviving the Lost Palms Oasis hike, I stopped by the visitor’s center on my way north through the park to let Ms. Arismendi know I was still alive. I told her that Munsen had eluded me. We resurrected the map and saw that Munsen could be approached from Chiriaco Summit Road, off Interstate 10, which connected to the sandy wash that led into the canyon. Sure it was going to be a nine-mile day, but it was better than trying to get there from Cottonwood again.

The wash was long and arduous going, but at least I knew where to go: to the right, where a canyon went up steeper and farther than one could see – and one could see a very long way – without revealing a hint of green.

Climbing into Munsen is something akin to a biblical trial. There is no path, no trail, just boulders stacked atop one another. Where you can, you climb over them. Where you can’t, you climb the hillsides to skirt them or crawl under them, through a series of shady caves and back up into the light.

Finally, after three hours saturated by yellows and browns and bleached whites, the first vibrant green burst into view. Although it was music to my soul, my first thought was: This can’t be it. There were only a dozen or so palms, and the book promised over 110. I wondered if a flood had wiped them all out, but this would’ve left considerable debris and there was none.

Forty-five minutes later I hit the second grove. It was even more beautiful. A pleasing network of puddles beneath the thriving palms reflected the oasis inversely, and fallen palm trunks acted as bridges over them. A charming side canyon punchbowl featured a stand of palms as well. It was picturesque, but we were nowhere near 110 palms yet, not even if you counted reflections.

I hiked further into the bleak boulders. At the third small grove I realized I’d been wrong to expect one sweeping forest of green. No, Munsen Canyon’s two miles of near-vertical bouldering would slowly reveal eight separate oases, plus two in side canyons.

In my zeal to explore to the very last palm (and still hoping for a sizable grove), I nearly ran out of water. I went on anyway, fully aware that anyone stupid enough to die from dehydration in an oasis is making himself an example of Darwinism.

I contemplated a foul-smelling puddle of turquoise water that had collected in the root cavity of a toppled palm. I wasn’t that desperate. To get a drink I would’ve had to sift through ropes of snotty green algae and pray that all the bighorn excrement scattered around didn’t necessarily mean I would contract an über dose of Giardia.

But before I hit that extreme I arrived at the final oasis, a collection of 13 healthy palms in a punchbowl that marked the end of Munsen Canyon. It was dazzling, and I felt paradoxically fantastic. Despite being utterly exhausted, I was strangely refreshed. And despite my thirst, I felt that a great inner-thirst had been quenched.

My goal: accomplished! Although on the surface this goal had been to lay eyes on every fan palm in Joshua Tree National Park, I’d also been chasing something more profound, and I’d finally found it in Munsen Canyon.

I turned to The Alchemist to see if there might be words to describe what I felt when I gazed upon that last stand of palms.

“You are in the desert,” said the author. “So immerse yourself in it. The desert will give you an understanding of the world. You don’t even have to understand the desert: all you have to do is contemplate a single grain of sand, and you will see in it all the marvels of creation.”

Yeah, it was something like that.

On The Trail Of The Desert Fan Palm

Hiking and Climbing Trails in Joshua Tree NP

Joshua Tree NP Overview

Desert Queen Ranch Tour

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Your GPS Navigation Systems

May Get You Killed

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Desert Survival Skills

- Successful Search & Rescue Missions with Happy Endings

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert

Survival Tips for Horse and Rider

- Preparing

an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms