Below Cooke’s Peak

Prehistoric Sites and More

by Jay W Sharp

Sometimes, relatively obscure places have served as grand stages for human drama—spiritual outreach, cultural exchange, treasure sought, travelers’ passages, deadly conflict, courage defined, military assertion, and, too often, tragic endings.

I often think of northwestern New Mexico’s Pueblitos – many village sites and lookout structures, all abandoned and most now in ruins. They marked a temporary merging of Puebloan and Navajo cultures, which joined together for protection against Spanish conquest from the east and Ute raiding from the north during the 17th and 18th centuries.

The hills, canyons and desert lands just south of Cooke’s Peak, in southwestern New Mexico, have served as a rugged desert setting for the long human pageantry of the region, but the story occupies little space in the history books. The state does not list it in its Recreation and Heritage Guide. The Bureau of Land Management, in its 1985 New Mexico Statewide Wilderness Study: Appendices Wilderness Analysis, did say that, “The historical component of this WSA [Wilderness Study Area, which encompasses most of the Cooke’s Range] is probably the most significant of all the WSAs in the Las Cruces District.” I would suggest that the significance extends well beyond that.

The Setting

Cooke’s Peak, rising 8,400 feet above sea level and some 3,600 feet above the surrounding desert floor, dominates Cooke’s Range, which is administered by the Bureau of Land Management. The name “Cooke” recalls Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, commander of the Mormon Battalion, which crossed the range in 1846. Easily visible from as far away as the Organ Mountains, some miles east of the Rio Grande, Cooke’s Peak served as a beacon for travelers crossing the Chihuahuan Desert. “In front we could see in the distance Cooke’s Peak, rising from the plain in bold prominence from among the surrounding hills,” commented Waterman L. Ormsby, The Butterfield Overland Mail. Ormsby, a journalist, was the only through passenger on John Butterfield’s inaugural westbound run, from St. Louis to San Francisco.

Cooke’s Range, a heavily faulted, north-south, igneous and sedimentary formation roughly 17 miles in length, lies some 12 to 15 miles north of Deming. Cooke’s Canyon, a rough three- to four-mile-long crevice that runs generally east to west, crosses the range south of the peak. It lies at the heart of the area’s history. Cooke’s Spring, one of the few dependable sources of water in the area, is located near the eastern end of the canyon. Mixed desert shrubs and tobosa grass dominate the plant community in the lower slopes of the range, and pinyon pine and juniper shrubs, the higher elevations. With its diverse natural habitats, the range hosts a considerable variety of wildlife.

Prehistoric Sites

Along the canyon trail and in the rugged lands below Cooke’s Peak, deadly conflicts (late 19th century) between the Chiricahua Apaches and the relentlessly expanding Anglo and Hispanic populations defined much of the history of America’s desert Southwest in this area. Earlier peoples, centuries to millennia ago, left evidence of their own chapters in the area.

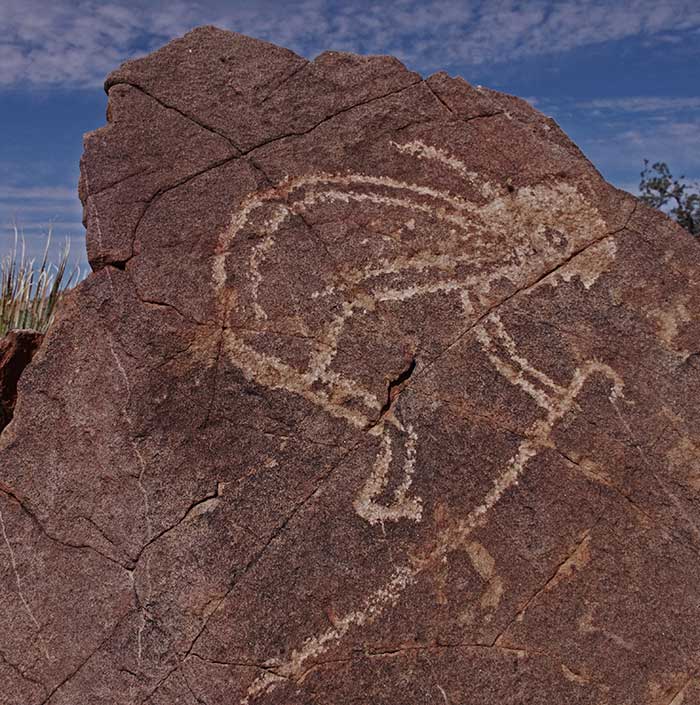

At the western end of Cooke’s Canyon, at a prehistoric living site near the juncture with Frying Pan Canyon, you will find images chiseled and scribed into rock surfaces –“petroglyphs” – that almost certainly speak to a center of ritual for hunting and gathering peoples some two to three thousand years ago and for early agriculturists six hundred to two thousand years ago. Telltale images of spear points suggest the reverence that the early hunter held for his weapon. Imaginative images of figures with goggle eyes and others with elaborate headdresses and decorated faces recall the ceremony and dance the early agriculturist shaman performed to petition the spirit world for the success of crops and the welfare of his people.

Just across an adjacent desert basin – Starvation Draw – immediately south southwest of Cooke’s Range, at a prehistoric living site called Pony Hills, you will discover still more petroglyphs left by the early agriculturists. Images, for instance, of goggle-eyed figures, human footprints, a mountain sheep, a rattlesnake and abstracted figures point to a rich, but enigmatic human story. A large human figure with a staff may represent a local interpretation of the famous Kokopelli, or hump-backed flute player, who played a central role in Puebloan mythology. Petroglyphs of a macaw (native, not to the Southwest, but to Central America and northern South America) and a stylized rabbit suggest cultural influences from the great Mesoamerican city states far to the south, in southern Mexico and Central America.

At some point, probably after the early agriculturists abandoned Cooke’s Range six to seven centuries ago for some unknown reason, an Athapaskan-speaking people, the Chiricahua Apaches, moved in to occupy the region. Over the succeeding centuries, they laid claim to the area as part of their homeland. Restless hunters and raiders, the Apaches left evidence of their presence in the detritus of their rancherias, or ephemeral campsites, which lie scattered across the slopes and through the canyons south of Cooke’s Peak. They would assert their right to the land when Anglo and Hispanic populations surged across the Southwest in the mid-19th century, drawn by the promise of conquest, opportunity, treasure and adventure.

The Rise of Conflict

Military forces, trappers, miners, drovers, emigrants, merchants and commercial transporters making their way across the Chihuahuan Desert often followed or crossed the trail that led through Cooke’s Canyon, capitalizing on its value as one of the few locations with a spring that offered a reliable source of water for travelers and their livestock.

In 1846, during the Mexican-American War, Lieutenant Colonel Cooke led his Mormon Battalion – troopers with their families – through what would become known as Cooke’s Range, across Cooke’s Canyon and past Cooke’s Spring in an epic march from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to San Diego, California. While the battalion helped secure the Southwest for the United States, it also capitalized on the march to garner U. S. government support in moving Mormon families westward, away from the persecution they suffered in Iowa.

Trappers followed the canyon trail in a quest for valuable pelts of animals of the wilderness, serving markets back east and sometimes depleting local wildlife populations. Prospectors came in search of mineral resources – gold, silver, copper and other profitable ores – often scarring the hillsides with forest clearings, trenches, prospect pits, shafts and mine waste. Vaqueros and cowboys came to drive longhorn cattle westward, some as far as California, to capitalize on vast virgin rangelands. Entrepreneurs like the celebrated Roy Bean came to establish new enterprises and serve newly established communities. Soldiers came – and some left – to answer the call of the Civil War. Adventurers came for the sheer excitement of exploring a wild new land.

In 1857, James E. Birch established a mail and passenger service that connected San Antonio and San Diego, and followed the trail through Cooke’s Canyon. The next year, John Butterfield followed suit, connecting Saint Louis to San Francisco—a 2,800-mile-long journey, the world’s longest stagecoach route. Both followed much the same route across the desert Southwest. Coaches from both services stopped at a newly built stone way station at Cooke’s Spring, where an onsite crew changed out draft teams and fed drivers and passengers.

Not surprisingly, the Apaches and their chief, Mangas Coloradas, saw this human wave as a threat to their homeland. “This major intrusion into the heart of Mangas’s country,” said Edwin R. Sweeney, Mangas Coloradas: Chief of the Chiricahua Apaches, “not only destroyed the Apache land but also psychologically devastated the Indians.”

As Sweeney said, “...it was inevitable that hostilities between whites and the Chihennes [the Chiricahua Apache band that viewed the Cooke’s Range as part of its homeland] would occur; after all, Americans were poaching and prospecting in some of the choicest regions of Apache country.” Meanwhile, the Civil War erupted. The stage lines terminated their service. American military forces transferred to battlefronts to the east. Although the Apaches did not understand the reasons for the withdrawals, it did seem, the Apaches thought, the ideal time to drive the remaining intruders from their land.

In the summer of 1861, Mangas Coloradas and his son-in-law Cochise – the two most prominent Chiricahua leaders of the time – set up a headquarters near Cooke’s Peak, or as the Apaches called it, “Dziltanatal,” (“Mountain Holds Its Head Up Proudly”), to develop and coordinate battle plans, according to Sweeney. They set ambushes “to kill as many whites as possible.”

They succeeded probably beyond anything they anticipated. They made the passageway through Cooke’s Canyon a “gauntlet of death.” During the course of their campaign, their forces killed, according to some sources, more than 400 travelers, leaving a grizzly wake of bones and makeshift graves along the canyon trail.

John Cremony, in his Life Among the Apaches, described the aftermath of one massacre in the canyon, “As I was the first to pass through Cooke’s Canyon after this affair, the full horror of the torture was rendered terribly distinct. The bursted [sic] heads, the agonized contortions of the facial muscles among the dead [who had been roasted, alive, over open fires], and the terrible destiny certain to attend the living [captured women and children] of that ill-fated party, were horribly depicted on my mind.”

Cooke’s Canyon became perhaps the most feared segment of the entire trail westward from the Rio Grande’s Mesilla Valley to California. As Sweeney said, “...in terms of fatalities, it exceeded the two most dangerous passes in southeastern Arizona – Apache Pass and Doubtful Canyon – combined.”

Fort Cummings

The situation grew so perilous that the Lincoln administration – even with the Civil War at its peak, in 1863 – felt compelled to commit the resources necessary to build and man a new post below Cooke’s Peak. It would become known as Fort Cummings. Its force would be charged with putting a stop to the massacres and raids by Mangas Coloradas’ and Cochise’s Chiricahua warriors.

Army Captain Valentine Dresher, Company B, 1st California Infantry, of the California Column was given responsibility for selecting the site and initiating construction. He chose to locate it at the eastern end of Cooke’s Canyon, beside Cooke’s Spring and the now vacated stagecoach way station. Cooke’s Peak stood prominently on the horizon to the northwest, a part of the view.

Dresher’s unit began construction of the fort in October of 1863. As W. Thornton Parker, an Army officer assigned to the fort later in the 1860’s, said in his book Annals of Old Fort Cummings, the brand new fort “presented an ancient look which...the American flag floating from the tall flag staff in the center of the parade ground looked almost out of place.” The fort’s adobe (“doby,” as Parker called them) walls, about 12 feet in height, “formed a huge square against which within the enclosure were erected the various buildings occupied by the garrison, i.e., the barracks, the hospital, the officers' quarters, the quarter-master and commissary departments, etc. Opposite from the main entrance there was a door going out to the hay stacks in the rear. The sentries walked their beats day and night at both entrances and there were also guards at the doors of the quarter-master and commissary departments. To the rear of the fort were huge piles of hay stored for the use of the cavalry and the quarter-master's department.”

The soldiers stationed at Fort Cummings found frontier life spartan. “The ‘doby’ buildings were low structures with flat roofs, built against the inner walls of the fort,” said Parker. “There were no outside windows even in the hospital. All the windows looked upon the parade ground — there were of course no outside windows in the fort walls. The floors were of dirt. In some rooms army blankets were fastened down with wooden pegs for carpets. In one corner of each room was a large open fireplace.”

The soldiers also had to be resourceful and watchful to protect themselves from venomous residents of the desert. “The legs of the bedsteads were in good sized tins containing water to prevent large red ants from crawling upon the beds. Overhead we nailed up rubber blankets, so that scorpions, centipedes, and tarantulas would slip off on to the floor, and be less likely to fall on the sleeper. Rattlesnakes got into our store rooms and into any open boxes, or among blankets and clothing.”

The soldiers faced continual strong reminders of why they had been assigned to Fort Cummings. “A settler in the sixties,” said Parker, “stated that he had counted nine skeletons while passing through [Cooke’s] Canyon, and the graves and heaps of stones which used to fringe the trail will long bear record of those dreadful times.”

“In 1867 the military authorities caused detachments of soldiers to collect the bones in the Canyon and to bury them in the post cemetery,” located on a hill not far south of the fort.

By the early 1870s, U. S. forces had largely suppressed the Apache threat to the Anglos and Hispanics in the lands below Cooke’s Peak, and soldiers began to withdraw, leaving Fort Cummings abandoned by 1873. The Army reoccupied the fort seven years later, however, when the Apaches, now under the leader named Victorio, launched a new campaign against the invaders of their homeland. Troopers operated out of the fort for the next six years, until the autumn of 1886, when the Apache wars finally ended once and for all with Geronimo’s surrender at Skeleton Canyon, in the southwest corner of New Mexico, near the border with Arizona.

Today, Fort Cummings, visited by few people, lies in ruins, with only a few “doby” walls still standing. The stagecoach way station also lies in ruins, with only remnants of its rock walls still in place. Cooke’s Spring is protected by a roofed rock structure called the “spring house,” built in the 1880s, although the water is no longer safe to drink. The cemetery, with scattered graves, many unmarked, stands as a grim reminder of the violent conflict of cultures below Cooke’s Peak in the late 19th century.

Nevertheless, as Parker suggested, the post held a firm place in the recollections of those who served there. “Fort Cummings!” said Parker, “What memories cling to its short but honorable record. Staunch and strong it seemed to derive inspiration from the glorious hills and arid mountains at whose feet it nestled. Here it stood, a shelter to its faithful garrisons, and a haven of refuge to the weary and imperiled emigrants and travelers who hastened to it for succor and relief.”

Below Cooke’s Peak Today

Now relatively few people make the effort to explore the remnants of the long and dramatic human history of the hills, canyons and desert lands below Cooke’s Peak. It can be a rewarding experience, especially if you have a knowledgeable guide for your first trip. (Unfortunately, many of the area’s markers and signs have been damaged or destroyed by vandals.)

You can reach Pony Hills and the Fort Cummings area by rough dirt roads that turn northwest off Highway 26, which runs from Deming to Hatch. You can access both of those locations by a high clearance vehicle.

As far as I know, you can still follow the old trail through Cooke’s Canyon, although on my last trip, the road was often very rough, especially in the vicinity of Frying Pan Canyon. You will certainly need a four-wheel-drive vehicle. As always in desert ventures, you should come amply supplied with water and prepared for emergencies. You should advise someone of your destination and plans.

The United States Geological Survey map titled “Deming New Mexico” will serve as a general guide to the area. You can acquire that map, and perhaps others, at the Bureau of Land Management office in Las Cruces:

U. S. Department of the Interior

Bureau of Land Management

Las Cruces District Office

1800 Marquess Street

Las Cruces, New Mexico 88005

Ph. 1-575-525-4300

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms

Click here to see current desert temperatures!