New Mexico's Pueblitos

A Navajo Legacy

by Jay W. Sharp

If you’ve traveled the southwestern United States and enjoy archaeology and history, you have probably visited the spectacular ruins of prehistoric communities in the Four Corners area, at Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, Mesa Verde in Colorado, Canyon de Chelly in Arizona, and maybe even Hovenweep in Utah. You have also probably dealt with the crowds of tourists who often pack campgrounds and trails and dilute the adventure at these famous locations.

You’ve probably never even heard, however, of another complex of ruins which stand like sentinels in northwestern New Mexico’s rugged, arid sandstone mesa and canyon country. These ruins mark a watershed period in the history of the Navajos. Even many people who live in the vicinity are unaware of these 17th and 18th century ruins, or that you can explore a number of them, hike nearby trails through juniper and pinion pine forests, see powerful Navajo rock art on canyon walls, and seldom encounter another visitor along the way.

Individually, these ruins, called "pueblitos," the Spanish word for "small villages," are modest in size compared to the more famous ruins, but collectively, they stand as one of the most extraordinary Native American achievements of the period. Today they offer adventurous travelers exciting opportunities for exploration and discovery. Archaeologists have found some 100 pueblito sites, and they believe that there may be as many more still undiscovered.

Pueblo ruins in Hovenweep National Monument. Photo by from Getty Images Signature

The story of the pueblitos has its roots in the violent, tumultuous Southwest of three centuries ago, when New Mexico’s Spanish colonialists battled to bring rebellious Indians to heel. Fighting had erupted across the Spanish northern frontier. Marauding tribes struck Indian and Spaniard alike, taking women, children, horses and guns. Slaves, called "genizaros" in New Mexico, became the currency of commerce. Indian refugees sought sanctuary in the mountains and plains and with other tribes.

The Navajos were, at the time, bands of nomadic foragers who lived in northwestern New Mexico,  in a homeland they called "Dinetah." They found themselves threatened not only by Spaniards from the east and south, but even more, by other Indian tribes, especially slave-hunting Utes, from the north.

in a homeland they called "Dinetah." They found themselves threatened not only by Spaniards from the east and south, but even more, by other Indian tribes, especially slave-hunting Utes, from the north.

Instead of fleeing, the Navajo bands decided to unite and protect themselves and their homeland, which covered sixteen hundred square miles, an area a third again larger than Rhode Island. They created a network of pueblitos that became the centerpiece of their strategy for defense.

First, they chose construction locations which were highly defensible. You can still see the results. You will find pueblito ruins at locations which would have discouraged assault by enemies on one hand and which offered broad overviews of approach routes on the other hand. Ruins lie atop steeply sloped mesas, for instance, overlooking canyons and streams. Oddly, you will also find isolated minuscule ruins, perhaps no more than a single stone room perched atop a large boulder, apparently positioned as network outposts. Presumably, the Navajos deployed a few individuals at such sites to afford early warning of raids.

Next, the Navajos designed their major pueblito structures to repel attack. Using locally available materials, they constructed fortified walls, maze-like accesses and dead ends to confuse and frustrate raiders. They incorporated small, strategically placed portals through which occupants could fire weapons at intruders. They camouflaged many villages so cleverly that they can scarcely be seen from a distance. At some of the pueblitos, the Navajos built defensive towers which resemble the 12th and 13th century Anasazi Hovenweep towers in southeastern Utah, near today’s Navajo reservation.

Chaco Canyon Ruins. Photo from Getty Images

Their architecture reflects a blend of cultures: Spanish style room-corner fireplaces with hoods; Pueblo style walls of stone and mud mortar; possibly Anasazi (Pueblo ancestor) style access shafts and towers. They continued building traditional Navajo "forked stick" hogans, or house structures, sometimes in the midst of the pueblito stone structures. You can still see the remains of some of the hogans, which were originally raised on a framework of forked Utah juniper logs and covered with small branches and mud plaster. In rare instances, the log frameworks still stand after more than 200 years.

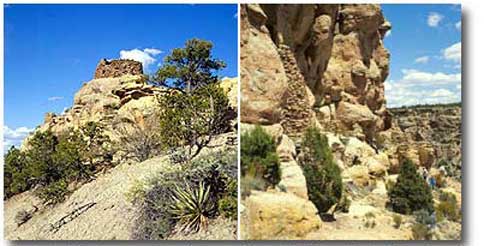

On the left are the remains of a pueblito which Navajos built on top of a large sandstone massif, which extends out from a large mesa. On the right is the shaft of a pueblito which the Navajos built nestled against a canyon wall. The shaft led to two living levels within the pueblito.

Finally, the Navajos positioned their pueblitos at sites which were not only defensible, but would also permit communication from one to the other, tying the communities together into an integrated network. Within minutes, communications could ripple across the network by signals such as direct visual contact or smoke or fire or by sounds such as rifle shots or drums. If one pueblito came under attack, it could notify neighboring pueblitos, which could rally quickly to its defense. Today, you can still see the ruins of some of the largest and apparently most strategically important pueblitos at intersections of lines of sight from several neighboring pueblitos, an arrangement which would have accelerated alerts and communications relays.

The pueblito network emerged as a testament to the resourcefulness and knowledge of the Navajo nomads. The concept of many small and widely dispersed defensible sites, fortified structures, a communications network and mutual defense was an ingenious, carefully planned alternative to the massing of people and forces at a few central fortified locations. That defensive strategy was impossible because of the meager resources of the Dinetah. The Navajo approach to defense required a level of familiarity with the land which archaeologists have so far been unable to duplicate, even with sophisticated computerized mapping systems.

The pueblito network emerged as a testament to the resourcefulness and knowledge of the Navajo nomads. The concept of many small and widely dispersed defensible sites, fortified structures, a communications network and mutual defense was an ingenious, carefully planned alternative to the massing of people and forces at a few central fortified locations. That defensive strategy was impossible because of the meager resources of the Dinetah. The Navajo approach to defense required a level of familiarity with the land which archaeologists have so far been unable to duplicate, even with sophisticated computerized mapping systems.

The unification of the bands for mutual protection not only bound the Navajos together, it produced unanticipated results which extended far beyond defense. Within a century, a short time period for major cultural change in technologically undeveloped societies, the Navajos evolved from primarily hunters and gatherers into primarily shepherds and farmers. The transformation was fueled, not only by a common cause, but also by livestock acquired through raids and trading and by agricultural technology acquired through Pueblo and Spanish contacts. You still see the echoes of the transformation on the Navajo reservation. Navajo women, wearing velvet dresses and turquoise and silver jewelry, still herd family sheep across the sage desert lands of Four Corners.

During the pueblito period, the Navajos absorbed Pueblo refugees who fled Spanish tyranny. The influx of a different culture further enriched the Navajos’ developing lifestyle. It helped trigger a flowering of ideas and creative experimentation, a rise of new clans, a synergism of philosophies, religions, cultures, crafts. You see the evidence in the vigor and power of the Navajo rock art which graces the surfaces of cliffs at the mouths of canyons, where there are veritable galleries of petroglyphs, or forms which Navajo shamans, or holy men, chiseled into the sandstone. These haunting images of tribal deities and sacred symbols served as shamanistic passageways into the spirit world.

Antelope House Ruins - Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Photo from Getty Images.

In the rock art, you will discover depictions of bows and arrows and animal tracks which speak strongly of the Navajos’ hunting and gathering past, portrayals of masked figures with horned headdresses which suggest contacts with Pueblo Indian ritual and dance, and even outlines of pyramid-shaped altars and corn plants which whisper of ancient influences from southern Mexico and Central America.

Jim Copeland, Bureau of Land Management archaeologist, explains a rock art figure of a Navajo deity which occurs near several pueblitos. On the stone surface to the right, a corn plant rises from a step sided pyramid shaped altar. Corn was introduced into the Southwest thousands of years ago from southern Mexico and Central Arnerica. The altar was an ancient symbol of the area.

The Navajos’ strategy for defense succeeded for a century, until about 1780, when they had to deal with major change once again. Relentless threats from the Utes, religious pressures from Spanish Franciscans, and a drought of enduring length combined to force the Navajos to abandon the pueblitos and the Dinetah and move to the south and the west, where they continue to live at the beginning of the third millennium.

The Navajos must have left their beloved Dinetah with profound grief, mourning their departure from the land where they transformed themselves from hunters and gatherers to the unified people we know today.

The current of the culture they brought from their homeland ran deep, however, and it continues to flow through Navajo life more than two hundred years after the Navajo exodus. It is reflected in a poem from an ancient healing ceremony called the Night Chant, which traditional Navajos still practice in sacred sites in the canyons of the Dinetah:

In beauty (happily) I walk.

With beauty before me I walk.

With beauty behind me I walk.

With beauty below me I walk.

With beauty above me I walk.

With beauty all around me I walk.

It is finished (again) in beauty.

It is finished in beauty.

The best and safest way to visit the pueblitos and the rock art sites, which are broadly scattered across rugged terrain, is to secure the services of a professional tour guide. Two who specialize in Four Corner area tours, including full and half day pueblito visits, are:

Aztec Archaeological Consultants, LLC,

210 S. Main Street,

Aztec, NM 87401,

(505) 334-6675

San Juan County Archaeological Research

Center at Salmon Ruins

P. O. Box 125

Bloomfield, New Mexico 87413

Ph 1-505-632-2013

FAX 1-505-632-1707

Contacts: Larry Baker, Executive Director, or Kurt Montoya, Educational Coordinator

Both organizations, staffed by professional archaeologists, know the pueblito ruins, their history, and the surrounding land exceptionally well. Either will design individual tours especially to accommodate your particular needs and interests. They will emphasize the importance of cherishing and preserving, not only the pueblitos, but all archaeological sites.

Plan to visit the pueblitos from spring through fall. Winter visits are possible, but the weather is unpredictable. Your family should wear good hats, good hiking shoes, long pants, sunscreen and sunglasses for protection from the sun and brush. You should also take a good insect repellent in case the mosquitoes and gnats decide you look tasty. You can make arrangements for transportation, meals and water through your tour guide.

Principal Sources

Powers, M. A. and Johnson, B. P., Defensive Sites of the Dinetah, New Mexico Bureau of Land Management, Cultural Resources Series No. 2, 1987

Marshall, M. P. and Hogan, P., Rethinking Navajo Pueblitos, New Mexico Bureau of Land Management, Cultural Resources Series No. 8, 1991

Note: Article was reviewed by Moore and Baker (above)

More..

Native American Desert Peoples Index

Prehistoric Desert Peoples Index

The Chiricahua Apaches: Cochise & Geronimo

Sojourn at Apache Pass

Touring Apache Country

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms