Termites

Six-Legged Terrorists

Termites, to us humans, amount to not much more than six-legged terrorists, sneaky creatures that slip up on us en masse to chew up our homes and buildings as well as cultivated and wild vegetation.

In hot and humid New Orleans, for an extreme example, Formosan termites – probably introduced unwittingly by a military transport vessel returning from Asia after World War II – have made it their mission to devour the entire city, especially the historic French Quarter. As furtive as jewel thieves, they build secretive 300-foot long tunnels to reach historic buildings, which – by the millions – they consume with gleeful and patient precision. The Formosan termites, probably unlike any other creature in all of New Orleans, took delight in Hurricane Katrina; they have used storm debris as vehicles for expanding their battlefront in their relentless campaign. (So far, only isolated colonies of Formosan termites have been found in the Southwest.)

In arid western Texas, desert termites have delivered a coup de grâce to millions of acres of drought-stricken and overgrazed pasturelands, leaving some areas “completely denuded,” according to Sharla Ishmael, writing for The Cattleman Magazine a few years ago. “It’s the beginning of a downward spiral called desertification,” she said. The termites “live in colonies deep down in the soil, with worker termites surfacing to feed on grasses, forbs, mulch, dry wood and dung.” During the height of the drought, desert termites in the upper one foot of 20 acres of western Texas soil consumed enough forage in the course of a year to feed a cow and her calf for more than a month.

Though our first instinct is to get rid of termites in our homes, termites do play an important role in Nature's unremitting process of recycling and renewal, especially those in the desert Southwest. “Termite ecology helps decompose woody plant materials [for instance, cacti skeletons] in a dry environment where decomposing fungi are limited because of a lack of moisture,” according to a publication issued by University of Arizona, Cooperative Extension, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. In a process known as “obligate mutualism,” a biologically primitive termite “worker’s gut can digest cellulose [the primary component of the cell walls of a plant] with the help of protozoa.” A more biologically advanced termite worker maintains an obligate mutualism with bacteria and fungi in the digestive process.

However, as said on the BugInfo Internet site, “...termites are not a discriminating lot.” As far as a termite is concerned, “...wood is wood!” even if it happens to be the frame of your home or a building. “If it used to be a tree, then it needs to be recycled [in the termite’s view], and the attempt is made, even if we aren’t actually done with the product just yet.”

Description

Typically, termites look something like cream-colored ants. Indeed, they sometimes get mistaken for ants. Biologically, however, they bear a closer relationship to cockroaches, said Paul B. Baker and Ruben J. Marchosky, Jr., in an informative paper called “Arizona Termites of Economic Importance,” University of Arizona, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

While the termite and the ant bear a superficial resemblance, they differ in several ways. Like all insects, of course, each has a head, thorax and abdomen encased in an external skeleton, and each has two pairs of wings and three pairs of legs. Each measures something less than a quarter of an inch to roughly half an inch in length, depending on the species. The termite, however, has a relatively wide connection between the thorax and the abdomen; the ant has a pinched connection. The termite has straight or slightly curved antenna; the ant has distinctly bent antenna. The termite, if swarming, has wings all of equal size; the ant, wings of unequal size.

The Termite Colony

Termites – like ants, honeybees and wasps – live in a feudalistic, socially stratified colony, in effect, a caste system, something like a miniature kingdom. They share shelter and food among a population of several thousand individuals, each with a designated purpose.

A queen, with her king, presides over the colony. The two produce offspring that may become royal successors, working peasants, soldiers, or winged colonists (alates). In founding a colony, the queen tends to her eggs and nymphs until enough workers emerge to take over those homemaking duties. She then becomes a termite reproduction machine. As she produces generations of offspring, she develops a greatly distended abdomen, which always contains a number of eggs. Depending on her species, she may live for a decade or more, producing hundreds to thousands of eggs in the course of a year. The king, ever faithful to his queen, helps her tend the colony at the beginning, and he mates with her throughout his life, making his contribution to the growth of the colony.

The royal successors, called “neotenic reproductives” by entomologists, “are a group of immature individuals that develop functional reproductive organs without ever leaving the nest,” said Baker and Marchosky. A pair may ascend to the termite “throne” of the colony as the queen and her king fail or die from old age. Or, in a process called “budding,” a pair of neotenic reproductives may establish a new kingdom in one part of the original colony should it somehow become isolated by breakage of connecting passageways or foraging tubes.

The working peasantry, or “workers,” comprise the largest caste within the colony. Not only do the workers, usually creamy in color, tend the queen and king, they take responsibility for “caring for the eggs and young larvae; constructing the colony foraging network; rebuilding tunnels and galleries when they are damaged; foraging for and providing food to alates, soldiers, and one another; assisting other termites when they molt; and grooming and cleaning nestmates,” according to Baker and Marchosky. In some species, the workers divide their duties based on sex and age. They may also come to the defense of the nest if it is attacked.

Soldiers, armed with powerful mandibles, or jaws, as well as defensive chemicals hold primary responsibility for protecting their colony against intruders, primarily predatory or pillaging ants. According to the paper, “Threat-Induced Defensive Behaviors in Termite Colonies,” by Colorado State’s David Stecco, the soldiers may also escort workers’ foraging expeditions to allow “the foragers to move farther from the nest in search of resources.” Depending on the species, the soldiers use their mandibles to club, stab or squash attackers. They may expel a sticky fluid to immobilize an enemy, sometimes, like a suicide bomber, sacrificing themselves for the cause. Able to identify ants based on chemical secretions, the soldiers may calibrate their defensive response to the aggressiveness of the specific species of an opponent, marshalling just enough force to drive off the intruders.

Several times a year, at the right conjunction of humidity, temperature, light, barometric pressure and wind speed, a termite colony’s alates – winged colonists – leave their home in a swarm, hundreds to thousands of aspiring queens and kings, taking flight, mating and establishing new colonies. They may meet other swarms of kindred termites, their ambitions all fired simultaneously by the same environmental cues, according to the Insects in the City Internet site, Texas Cooperative Extension, Texas A&M University. A female produces a fragrance that a male finds irresistible. Two termite lovers may pair up airborne, sometimes in the romantic glow of a streetlight. They alight on the ground, shedding their wings. Together they choose a place to set up housekeeping. They excavate their nuptial chambers from wood or moist soil, where they mate and the new queen lays her eggs to begin their new colony. Fortunately for human beings, the royal couple, with their lives determined by fate, will have less than one chance in a hundred of succeeding in their enterprise, according to Baker and Marchosky. Most swiftly fall prey to opportunistic insects, arachnids, reptiles, birds and mammals.

Termites of the Southwest

Our termites here in the desert Southwest fall into one of three species groups: dampwood, drywood and subterranean. Collectively, the groups include several dozen species. (More than 2,000 species exist worldwide.)

Dampwood termites, say Baker and Marchosky, span the Southwest. Typically, they take up residence – as their name would imply – in and around damp wood that is in contact with moist soils, maintaining a relatively small termite colony of perhaps 1,400. “The desert dampwood termite...attacks living or partly living desert shrubs and even young citrus trees, utilizing the sap of these plants for needed moisture,” said the authors. One typical species, the Paraneotermes simplicicornis, swarms from late May through September, often at dusk of the day following a strong summer rain. Although not a major pest, it may infest continually damp wooden structures.

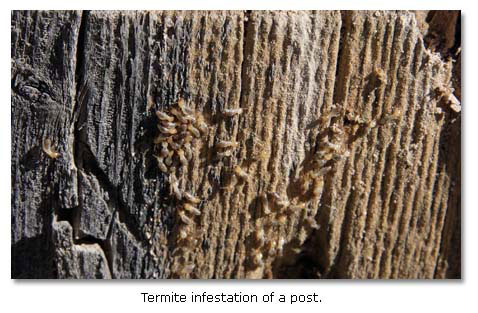

The drywood termites also have a range that extends across the Southwest, often in the hotter and dryer regions of our deserts. Requiring no contact with moist soil, they establish colonies of several thousand in sound dry wooden structures, for instance, dead tree limbs, posts, poles, lumber, and home and building structures. The Marginitermes hubbardi species, which may swarm as many as 20 times around sunset from June into September, infests trees along streambeds and cactus skeletons on the desert floor, but it especially seems to relish sound, dry wood in manmade structures. The species Incisitermes minor, which usually swarms on bright sunny days in June through August, ranks as the most widely distributed and destructive drywood termite in the Southwest, according to Baker and Marchosky. It may “attack flooring, windows, doorframes, soffits, fascia boards, and even roof sheathing.” Both the M. hubbardi and the I. minor species appear to be looking forward to human invasion of their natural habitats.

“Subterranean termites are among the most abundant but cryptic of animals, a factor making behavioral studies very difficult,” say University of Arizona entomologists Jeffery P. La Fage, William L. Nutting and Michael I. Haverty said in their paper “Desert Subterranean Termites: A Method for Studying Foraging Behavior.” Occurring across the Southwest, they construct concealed underground colonies with many thousands of workers that work like a stealthy multitude of saboteurs in attacking our wooden structures. (The voracious Formosan termite belongs to the subterranean group.) They cause more economic damage than the dampwood and drywood groups combined. Across the nation, they account for some billion dollars a year in termite control, say Baker and Marchosky. The widespread and destructive Reticulitermes tibialis species, or arid land subterranean termite, which favors higher, less harsh environments, swarms during the daylight hours of midsummer and possibly into the winter. If it builds a colony near a building, it can construct shelter tubes, or covered passageways, over concrete foundations to invade structural wood within the structure. The species Heterotermes aureus, which can tolerate high heat and extreme drought, holds top spot as the most destructive termite within its range, from southern Arizona to southeastern California. This species swarms at dusk following a rain during the summer monsoon season. If it colonizes near a building, it can build elaborate shelter tubes from its underground chambers to reach structural wood. “It can attack hardwoods readily,” say Baker and Marchosky, “and has been reported to attack Sonoran ironwood.”

Signs of Termite Presence and Control of Termites

While termites attack your house or building in secrecy, they may still signal their presence in several ways. Alates may appear as uninvited and unwelcome guests in your home. They may leave their shed wings beneath a light. Workers may produce visible holes in wood structures. Drywood termite workers may leave recurrent piles of sawdust-looking fecal pellets beneath holes. Subterranean termite workers may construct shelter tubes that lead from the soil up concrete surfaces to wood structures. Often described by biologists as “cryptic,” or secretive, termites may elude discovery for a substantial – and destructive – period of time.

In infested areas, the termite threat may call for annual inspections by a pest control professional, who may detect them through wood-probing techniques, non-invasive (and expensive) high-tech methods, or even specially trained (and expensive) termite-sniffing dogs. A termite battle may have to be fought with wood replacement, fumigation, liquid termiticides or baiting systems.

Keeping a close watch for the six-legged terrorists, say Baker and Marchosky, “allows control methods to be employed contemporaneous to the infestation, reducing the risk of serious structural damage to the home.”

By Jay W. Sharp

More...

Animals and Wildlife

Fire Ant

Velvet Ants

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms