The Yucca

Desert Food Chain Producers - Part 4

If most cacti bristle with arrays of modified leaves, or spines, that look like pins and needles or fishhooks, most yuccas – unlikely members of the symbolically peaceful lily family – guard themselves with armaments of leaves, not spines, that resemble sabers. Like the cacti, the evergreen yuccas – producers – serve up tasty meals to various animals – the consumers – in spite of the threatening botanical weaponry.

In fact, the yuccas held such an important role in the diets (as well as the economies) of the Native Americans that the plants became embedded in folk histories, ceremony and tradition. For one example, in The Dîné: Origin Myths of the Navaho Indians (recorded by Aileen O’Bryan, Bulletin 163 of the Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution, 1956), “The Plan, or Order of Things,” declared that “There was a plan from the stars down…

“…they planned how a husband and a wife should feel toward each other, and how jealousy should affect both sexes. They got the yucca and the yucca fruit, and water from the sacred springs, and dew from all the plants, corn, trees, and flowers. These they gathered, and they called them tqo alchin, sacred waters. They rubbed the yucca and the sacred waters over the woman's heart and over the man's heart. This was done so they would love each other; but at the same time there arose jealousy between the man and the woman, his wife.”

Emblems of the Desert

Typically, the yuccas, emblematic of the desert, suggest sprays of broadswords or rapiers that crown either a root-stem, a single stem or branching stems. Altogether, at least four dozen species occur in their native range of the western United States, Mexico, Central America and the West Indies. More than a dozen species populate our Southwestern region, growing from the bottoms of desert basins to the upper slopes of mountain ranges.

One of the most widely distributed, the Banana Yucca, has extended its range “from the mountains of the eastern Mohave Desert of California across southern Nevada, southwestern Utah and southwestern Colorado as far east as Trinidad. From this northern boundary it extends south and southeast across northern and central Arizona and the greater part of New Mexico into southwestern Texas,” according to Willis H. Bell and Edward F. Castetter, writing in the Ethnobiological Studies in the American Southwest, “VII. The Utilization of Yucca, Sotol, and Beargrass by the Aborigines in the American Southwest,” 1941.

Collectively, the desert species of yucca, all well equipped for surviving under harsh conditions, have several distinctive characteristics.

Their sharply pointed succulent (or, water-storing) leaves bear grayish- or bluish-green waxy skins that both reflect the heat of the desert sun and restrict the loss of stored water. The rosette leaf arrangements and the often channeled upper leaf surfaces function as conduits for funneling water from rains, snowmelt and dew into the plant stem and root system. Most desert species’ leaves signal their botanical identity with tendrils of fiber that curl away from the edges.

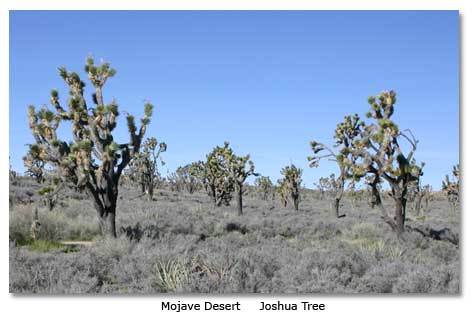

The yucca stems have a “vascular” structure, or scattered bundles of specialized tissues that store and conduct water. Some species, for instance, Our Lord’s Candle, a yucca of the western Sonoran Desert, have very abbreviated stems, or “root stems,” that barely reach the surface of the ground. Others, like the Banana, or Datil, Yucca (of all three deserts) have very short or sometimes, “reclining,” stems. The Soaptree Yucca (Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts) and the Torrey Yucca (Chihuahuan Desert) have stems, sometimes shaggy with skirts of dead leaves, that can range from several inches to 10 to 15 feet in height. That star of the yuccas, the Joshua Tree (Mojave and Sonoran Deserts), has multiple branching fibrous stems as tall as 40 or 50 feet. Some yucca species that grow in dune fields, for instance, the Soaptree Yucca of northern Chihuahua’s Médanos de Samalayuca (Sand Dunes of Samalayuca), have stems that grow taller very rapidly – as much as several inches per year – to keep the leaf rosettes from being engulfed by the marching dunes.

Some species have both shallow radial root systems and deep tap roots. The radial roots intercept rain water and snow melt as it soaks into the upper soil layers. (Other species have a more limited root system.) The tap roots reach for the deeper water in the lower soil layers, and they have fleshy tissues for storing and conducting water. The roots stake out a claim for water and nutrient resources, guarding a plant’s “territory” against encroachment by neighboring yuccas and other plants.

Typically, the yuccas produce a dense bouquet of creamy white flowers, sometimes with a reddish or purplish tinge, on a single stalk in the spring and early summer, attracting a specialized pollinating moth species, and they follow with an equally dense cluster of fleshy green edible fruits during the summer, attracting a veritable lunch line of consumers.

Like cacti, the yuccas minimize the evaporation of water from their tissues by opening their stomata (leaf pores) during the coolness of night (rather than during the heat of the day) to take in the carbon dioxide required for photosynthesis. They open their stomata as darkness falls. They effectively inhale the carbon dioxide through the night. They put it in short term storage by combining it, biochemically, with an organic acid. They close their stomata as darkness gives way to sunlight. They free their store of carbon dioxide internally. Fueled by solar energy, they begin the process of photosynthesis, which they continue through the day.

By comparison, many other plants open their stomata for business at sunrise. They take in the carbon dioxide during the heat of the day and proceed directly with photosynthesis, without the intermediate step of short-term chemical storage. More efficient, these plants tend to grow more rapidly, but they also squander much of their water store by evaporation through their stomata.

Representative Members of the Yucca Family

Generally, the yuccas of the Southwest fall into one of two groups, the broad-leaf yuccas, with mature leaves that measure roughly two inches in width, and the narrow-leaf yuccas, with mature leaves that measure well under one inch in width. Some of the better known species include the broad-leaf Banana and Torrey Yuccas and the narrow-leaf Our-Lord’s-Candle and Soaptree Yuccas and, of course, the Joshua Tree Yucca.

The Banana Yucca holds residence in the Sonoran, Mojave and Chihuahuan Deserts. As described in the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center internet site, its 30-inch-long leaves typically occur in an open cluster atop abbreviated stems. It has a fibrous and highly branched radiating root system. Its flower stalk reaches as much as 40 inches in height, bearing fleshy white flowers with a red or purple tinge. Its produces a green, fleshy, banana-shaped fruit, hence its common name.

The Torrey Yucca, or Spanish Bayonet, a signature plant of the Chihuahuan Desert, closely resembles the Banana Yucca, with both having similar leaves and radiating root systems, and the two species, in fact, may be hybridizing, according to Clark Champie in his Cacti and Succulents of El Paso. The Torrey Yucca, however, has a rising and shaggy skirted stem that may reach 15 feet or more in height. It produces creamy white flower clusters and fleshy fruits on a stalk that sometimes extends for several feet above the leaf rosette.

Our-Lord’s-Candle, native to the western Sonoran Desert, has a decorative “dense basal rosette of gray-green, rigid, spine-tipped leaves” that span about two feet, according to the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center internet site. It has a branched radiating root system. It produces, on a single 10- to 15-foot stalk, a dense cluster of purple-tinged, cream-colored, bell-shaped flowers and a juicy, tender but seed-filled fruit. Its blossoms almost seem to glow in the soft light of dawn or sunset, giving the plant its name. Unlike other yuccas, Our-Lord’s-Candle dies once it has bloomed.

The Soaptree Yucca, among the most common of the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Desert yuccas, has pale green leaves with whitish margins. As it grows and matures, it often develops a branching, shaggy stem perhaps 15 feet in height. It has both a radiating root system and a tap root. Each stem branch produces a cluster of cream-colored bell-shaped flowers and brown woody seed capsules that tip a flower stalk several feet in length.

The Joshua Tree yucca, the patriarch of the clan, holds primary residence in the Mojave Desert. It’s leaves, according to Richard Katz’s “Botanical Profile of the Joshua Tree,” Flower Essence Society web site, measure about five to 12 inches in length, becoming “sword-like in their intensity” as they mature. Resembling a plant you would expect to find in a Hollywood version of an alien world, a mature Joshua Tree has a bizarrely branched stem, a result of its inclination to add new growth from the site of a blossom cluster. According to the Blue Planet Biomes web site, the Joshua Tree “has two sets of root systems, one stores any surplus water and it also develops bulbs. The bulbs are buried 10 to 30 feet under the soil. Sometimes they reach up to 4 feet in circumference and weigh up to 40 pounds. The other set is a shallow root system; the shallow roots only reach down to a couple of feet.” The Joshua Tree blooms annually, provided it receives enough rain. Upon flowering, “the light cream or ivory colored waxy blossom emits a ‘musty odor similar to that of a toadstool’ and reveals a seedpod that is ‘raspberry’ or artichoke in shape. …these blossoms open only at night and only partially, which is considered rather unusual,” said Graeme Somerville in his paper, “The Biogeography of The Joshua Tree,” San Francisco State University Department of Geography web site. The Joshua Tree, which may live for centuries, received its name from Mormon pioneers who thought the plant looked like the Biblical prophet, his arms raised, beckoning them across the desert wilderness to the promised land.

A Botanical General Store

The yuccas serve not only as a grocery store for insects, reptiles, birds and mammals – filling an important niche in the desert food chain – they also answer needs for housing, tools and raw materials for the consumers. In fact, for some yucca species, virtually every part – from the leaves to the stems to the roots to the flowers and fruits – winds up on the shopping list of some consumer, frequently including man.

For example, yuccas provide seed stores for feeding the larva of the yucca moth, a partner in a textbook example of “mutualism,” by definition, a biological relationship in which both parties benefit. In the spring, when the yuccas flower, their whitish blossoms give refuge to the moth during the day. Their ovaries serve as a depository for the eggs laid by the moth during the night. The fruits contain the food seeds, stacked like poker chips in the pod, for feeding the larva until they emerge from the hull to pupate. In return, the yuccas receive pollination by the yucca moth, the only insect that renders the service. In essence, the yucca and the moth evolved in a kind of extraordinary biological minuet, with each essential to the survival of the other.

For example, yuccas provide seed stores for feeding the larva of the yucca moth, a partner in a textbook example of “mutualism,” by definition, a biological relationship in which both parties benefit. In the spring, when the yuccas flower, their whitish blossoms give refuge to the moth during the day. Their ovaries serve as a depository for the eggs laid by the moth during the night. The fruits contain the food seeds, stacked like poker chips in the pod, for feeding the larva until they emerge from the hull to pupate. In return, the yuccas receive pollination by the yucca moth, the only insect that renders the service. In essence, the yucca and the moth evolved in a kind of extraordinary biological minuet, with each essential to the survival of the other.

The yuccas (especially during the flowering and fruiting season) become a veritable banquet table for the consumers. For example, the leaves attract black-tail jackrabbits, desert cottontail rabbits, woodrats and packrats. The stems draw various insects. The roots provide food for pocket gophers. The blooms, fruits and seeds attract arthropods (invertebrate animals with jointed legs and a segmented body, for instance, the insects), song birds, game birds and rodents. The flower stalks may become food for antelope, mule deer and elk. Even dead yuccas feed consumers, for instance, termites.

Yuccas also offer accommodations for wildlife. The Soaptree Yucca, for instance, opens its botanical apartment doorway to the Cactus Wren, the Scott’s Oriole, flickers, the Swainson’s Hawk, the Aplomado Falcon and others. It offers temporary perches for many birds. The Joshua Tree stem gives shelter to the Desert Night Lizard, one of the smallest reptiles in the world.

For the highly resourceful Native Americans, the yuccas not only served as an important food source, they furnished fibers for making clothing, basketry, mats, cordage, netting, cradles brushes, bindings, bowstrings and gaming pieces, according to Bell and Castetter. Leaves became a poltice for treating sore eyes; leaf points, awls for sewing leathers and fabrics and piercing ears; leaf fibers, brushes for combing hair and painting ceramics; leaf juice (mixed with a powder made from scorpions, red ants, centipedes and jimson weed), a potion for poisoning arrow points; fresh roots, a detergent for washing bodies, clothing, fresh hides and scalps; dead roots, a fuel for firing pottery; dead and dried flower stalks, tools for making fires; long flower stalks, lances for fighting enemies; fresh flower stalks, construction material for building lodge walls; and the emulsion, a medicine for treating insect and snake bites.

The Banana Yucca, a Jemez Puebloan told Bell and Castetter, “was the most important of all wild fruits. [The Puebloan] recounted [a] method of preparation known to all the pueblos which consisted of splitting the fruit into halves, removing the seeds, and allowing the halves to dry. Much the commoner method, however, was to peel the fruit and dry the pulp, which was afterwards worked into a cake and dried further. The Jemez boiled the pieces of cake with water and drank the sweet liquid.”

Banana Yucca “was abundant in the mountainous country inhabited by the nomadic Yavapai [of the Sonoran Desert] and was one of the wild crops to be gathered in its season…” said Bell and Castetter. “The Northeastern Yavapai ate the fruit after boiling [it] in water and in addition gathered the tender flower stalks before blossoming and prepared them for use by roasting in the fire…”

A narrowleaf yucca helped replenish the Chiricahua Apaches’ larders during the spring, when “the clusters of white flowers…are in bloom,” said Morris Edward Opler in his An Apache Life-way. “These are gathered and boiled with meat or bones. Any surplus is boiled, dried, and stored. The buds of still another variety of yucca (unidentified) are opened and dried. During the process they must be impaled on sticks ‘as you dry peaches; you cannot put them on a hide because they would stick to it [said Opler’s Chiricahua informant]…These are used to sweeten drinks.”

“In the opinion of the authors,” said Bell and Castetter, “yucca ranked foremost among the wild plants utilized by the inhabitants of the Southwest.”

Next The Agave Role as a producer

Some yuccas (scientific and common names) of the deserts:

Sonoran Desert Yucca Species

Y. aloifolia (Spanish Bayonet)

Y. baccata (Banana Yucca, Datil)

Y. brevifolia (Joshua Tree)

Y. elata (Soaptree Yucca, Palmella)

Y. rigida (Blue Yucca)

Y. whipplei (Our Lord’s Candle)

Y. valida (Datilillo)

Mojave Desert Yucca Species

Y. baccata (Banana Yucca, Datil)

Y. brevifolia (Joshua Tree)

Y. schidigera (Mojave Yucca)

Chihuahuan Desert Yucca Species

Y. baccata (Banana Yucca, Datil)

Y. elata (Soaptree Yucca, Palmella)

Y. faxoniana (Spanish Bayonet

Y. rigida (Blue Yucca)

Y. schottii (Schott Yucca)

Y. thompsoniana (Beaked Yucca)

Y. torrevi (Torrey Yucca, Spanish Dagger)

![]() Click Here for a short video on how the Food Chain works

Click Here for a short video on how the Food Chain works ![]()

Index

Part 1 Desert Food chain - Introduction

Part 2 Desert Food chain - The Producers

Part 3 Desert Food chain - The Cacti: A Thorny Feast

Part 4 Desert Food chain - The Yuccas

Part 5 Desert Food chain - The Agave

Part 6 Desert Food chain - Desert Grasslands

Part 7 Desert Food chain - Desert Shrubs

Part 8 Desert Food chain - The annual forbs

Part 9 Desert Food chain - Mavericks of the Desert Plant

Part 10 Desert Food chain - Outlaw desert plants

Part 11 Desert Food chain - Animals: The Consumers

Part 12 Desest Food chain - The Insects

Part 13 Desest Food chain - The Ugly, the Uglier and the Ugliest

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Death by GPS

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Maps Parks and More

- Desert Survival Skills

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert Rocks, Minerals & Geology Index

- Preparing an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms