Jornada del Muerto Trail

Dead Man's Journey

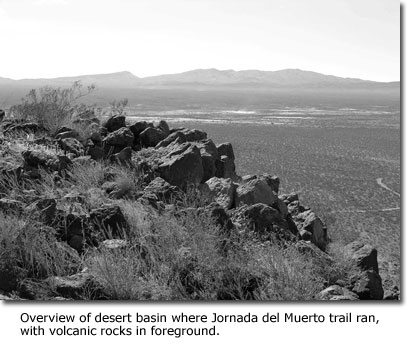

Overview of the hard, dry desert basin through which the Jornada del Muerto trail ran. The Caballo Mountains lie in the background, to the west. Beyond the Caballos, the Rio Grande follows its course southward.

Headed southward toward Mexico in the summer of 1670, over a trail through a foreboding desert landscape bounded by dark and sullen mountains to the east and west, a party of five traders made a grim discovery. Later, one of the traders, Francisco del Castillo Betancur, would say, in a letter to a friend, that they had found "a roan horse tied to a tree by a halter. It was dead and near it was a doublet [a short-waist jacket] or coat of blue cloth lined with otter skin. There were also a pair of trousers of the same material, and other remnants of clothing that had decayed…" Searching the area, the party soon found "hair and the remnants of clothing… I and my companions," said Castillo, "found in very widely separated places the skull, three ribs, two long bones, and two other little bones which had been gnawed by animals." (I have taken the quote from Joseph P. Sanchez's The Rio Abajo Frontier 1540-1692.)

The traders suspected that their discovery spoke of murder, but they could have known nothing of why or just how it happened.

They gathered the human remains and carried them on southward to El Paso del Norte, today's Juarez, across the Río Grande from El Paso. They left them for burial by a Franciscan friar at La Conversión de los Mansos y Sumas, a mission church on the south side of the river. They continued southward, on down the trail toward Parral.

Bernardo Gruber, Trader

Two years before the five traders discovered human bones scattered across the

desert, a man named Bernardo Gruber – a German immigrant and itinerant

trader from Sonora – made his way northward, likely following the trail

through the foreboding desert landscape. Accompanied by three Apache servants,

including a teenage boy named Atanasio and two women, he led a pack train that

included 10 pack mules, 18 horses and three oxen. "His mules bore fine

stockings, gloves, embroidered cloth, buckskins, and iron tools and weapons," said

Marc Simmons in his Witchcraft of the Southwest.

Gruber would certainly have known that the route, which lay east of the Rio Grande and the Fra Cristobal and Caballo mountain ranges, crossed one of the most punishing parts of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro—the old Spanish road that connected Mexico City with Santa Fe. Some 30 to 40 leagues (roughly 90 miles) in length, across desert sand and rock, it passed not a single spring or stream, not a single dependable waterhole. It offered little forage for mules, horses and oxen. It left the thorns of its cholla and prickly pear cacti embedded in the flesh of travelers. It often took a week or more to traverse since caravans often covered only eight to 12 miles a day. Gruber certainly knew that this passage could inflict a terrible toll on man and animal, but it offered a shorter, much less rough route than the alternative.

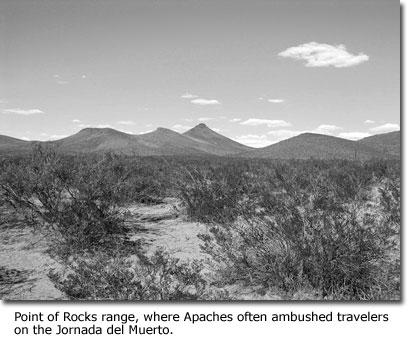

Gruber must have known, too, that this part of the trail intruded into the range of the Mescalero Apaches—notorious and deadly raiders. He had likely heard that the Apaches often ambushed Spanish caravans and trading expeditions at a small range called Point of Rocks, near the southern end of the trail, or beside the desert playa called Laguna del Muerto, or Lake of the Dead, near the middle of the trail. He would not have been surprised to learn that Franciscan Fray Juan de Paz would say (in a quote recalled by John L. Kessell in his Kiva, Cross and Crown) that "…the whole land is at war with the very numerous nation of the heathen Apache Indians… No road is safe. One travels them all at risk of life for the heathens are everywhere." Gruber, however, may have felt comparatively safe. After all, he had Apaches for companions, and he brought goods for trade with the Indians.

As he drew near the Spanish settlements and pueblo missions in what is now central New Mexico, this German trader may not have known – or fully appreciated – that the Spanish Inquisition had extended its malignant tentacles, not only across continents by the 17th century, but even up El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro and into the Southwest. A native of Europe, Gruber likely knew that the Inquisition in Spain cast a dark and terrible pall of fear over every citizen whose veins carried the blood of the Jews or the Moors, anyone whose religious beliefs strayed even slightly from the strict teachings of the Faith, anyone whose behavior suggested the practices of witchcraft, anyone whose enemies brought accusations or even suggestions of contaminated racial blood or heresy or sorcery. Gruber likely knew that the Inquisition in Spain could imprison and torture anyone even vaguely suspected of violating the "edicts of the Faith." It could hold anyone indefinitely without ever revealing the identity of accusers or the nature of offenses. It could seize anyone's property with no compensation even if they proved innocent of the charges.

So far away from Europe, however, the German – "El Alemán," they called him, in Spanish – might not have realized, or fully appreciated, the influence and control of the frontier friars, empowered by the Inquisition. As in Spain, "…the citizens [of New Mexico]," said Kessell, "stood defenseless and fearful before the arbitrary justice of the Franciscans. For no greater offense than hiring an Indian laborer against the will of a friar, New Mexicans were threatened with prosecution by the Inquisition. Such intimidation was commonplace."

Bernardo Gruber, Sorcerer?

The risks notwithstanding, Gruber negotiated the trail through the foreboding

desert landscape, and he took his expedition on northward, along the banks of

the Río Grande. At some point, Gruber led his pack train to the southeastern

flanks of the Manzano Mountains, at the northern end of the vast Chihuahuan Desert.

He apparently meant to spend several months there, trading with the peoples of

the Quarai and Abó pueblos, where he knew that the Franciscan fathers

had established mission churches. He likely did not know, however, that three

Franciscan priests at Quarai had held jurisdiction for enforcement of the "edicts

of faith" or that the convent at Quarai had space designated specifically

for use by the Inquisition.

During his stay, Gruber impressed the Puebloans with his fine clothing—a "doublet, which is a short-waist jacket," said Sanchez, "and pantaloons with woollen (sic) stockings. To keep warm, the German wrapped himself with an elkskin overcoat."

Apparently, Gruber carried on his business routinely until Christmas morning of 1668. For some strange reason, during mass that morning at the Quarai mission church – Nuestra Señora de las Purísima Concepción – Gruber and a friend, Juan Martín Serrano, climbed the ladder to the choir loft. As mass proceeded, Gruber took several papelitos (small pieces of paper) from his pocket, according to Sanchez, and he and Martín wrote on 11 of them mysterious letter combinations separated and bracketed by crosses: "+ ABNA+ADNA+."

Gruber whispered to the choir members: "He who eats one of these slips of paper, will, from that hour of this first day to that same hour of the second day, be free from any harm, whether it be caused by knife or shot." The effect would only last, said Gruber, through the first day of Christmas. Gruber gave a couple of the marked papelitos to Juan Nieto, a 19-year-old who indicated that he wanted to be "free from any harm."

Gruber probably did not know that within the hour after the mass young Nieto would stand within a pueblo ceremonial chamber, or kiva, before a group of curious Indian men. He swallowed one of the papelitos. He then stabbed his hand and wrist with an awl, and to the amazement of the spectators, he suffered no injury. He then repeated the performance in the pueblo community house, swallowing the second of his papelitos and stabbing himself with a dagger. Again, to the amazement of the spectators, he suffered no injuries. The young Nieto then announced that the whole thing had been had been a hoax—just a big joke. He had faked the stabbings. He did not believe in the slightest that the papelitos would keep him "free from any harm."

Later, Gruber himself faced a challenge by Juan Martín Serrano, who had accompanied him to the choir loft. With Nieto watching, the two drew their swords. Gruber said, according to Sanchez, "This is how the test should be made!" He backed down Martín, who clearly had no faith in the papelitos.

Gruber probably did not anticipate that a few days later, Juan Nieto, encouraged by his wife, would report the incidents to the Inquisition.

Bernardo Gruber, Defendant

Through the cold winter, said Sanchez, Gruber, probably unsuspecting

that he might be in the sights of the Inquisition, remained near the protective

southern end of the Manzano Mountains, trading at the Quarai and Abó pueblos

and caring for his livestock. With the coming of spring, Gruber received unexpected

orders from Fray Paz – an agent of the Holy Office of the Inquisition – to

remain in the area. Surely, Gruber's anxieties rose. About 10 o'clock at night,

on April 19, 1668, as he walked into the Quarai community house, the same one

where Nieto played his Christmas joke on the Indian men, Gruber found himself

under arrest by Fray Gabriel Toríja, a notary for the Inquisition, who

was accompanied by an officer and Juan Martín Serrano (the same individual

who accompanied the German to the choir loft in the mission church) and Juan's

brother Joseph.

This, however, was no joke.

Gruber surrendered without a struggle.

With all mounted on horses they appropriated from him, Gruber and his captors rode through the night to Abó, where he would be held prisoner. The next day, he received a visit from Fray Paz, who came to verify an inventory of property. Believing that he could prove his innocence, Gruber asked for an expedited hearing by the Inquisition.

He tried to explain, said Simmons, that the poor in his country, Germany, often used cryptic letters on small pieces of paper to invoke magic. Surely, such a small thing could not be considered as a serious offense by the Spanish Inquisition.

Surely, that did not warrant imprisonment.

He learned, however, that Paz believed him to be a sorcerer who had, according to Sanchez, "promised immortality to Juan Nieto on a holy day inside a church while mass was being said and he had used a mysterious formula to work his charm. There would be no pardon…"

After a month at Abó, which lacked an adequate cell, Gruber was forcibly taken, in shackles and under guard, northward up the river to a more secure imprisonment at an hacienda near the Sandía Pueblo. There, he would languish in a single small room with a single door and a single wooden-barred window for more than two years. He saw no indication by the Holy Office of the Inquisition that he would have an opportunity to respond to the charges within the foreseeable future. Outside his care, his mules and horses fell into other hands or died of neglect. His trade goods began to disappear. His young Apache servant Atanasio disappeared.

Clearly desperate, Gruber began to plot his escape.

Somehow, he secretly enlisted the help of Atanasio, who had apparently returned covertly to the area, and of Juan Martín Serrano, who had accompanied him to the choir loft and who later helped arrest him at the Quarai community house. He instructed Atanasio to prepare the way for an escape. He persuaded Martín to secure supplies and a harquebus (an early firearm). Gruber, feigning illness, convinced his guards that they should remove his shackles. In moments alone, he begin loosening the wooden bars of his single window.

Bernardo Gruber, Escapee

On June 28, 1670, the agents of the Inquisition learned that El Alemán

had escaped, according to Sanchez. His tracks showed that he had fled south,

accompanied by Atanasio, down El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, a route that

would take him over that trail through the foreboding desert landscape, down

and across the Rio Grande and into Mexico. He had eluded pursuit. The friars

and the Spanish governor rushed messengers to alert the Holy Offices of the Inquisition

in Chihuahua and Sonora. Eight soldiers and 40 Indians gave pursuit as far as

El Paso del Norte.

The found no trace of El Alemán. He had simply vanished.

Days later, Inquisition authorities would learn that El Alemán – weakened by his long captivity and suffering from complete exhaustion and terrible thirst on that hard desert trail between dark and sullen mountains – had collapsed at a waterless place called La Penuelas. He had given Atanasio his harquebus and sent him on southward, down the trail for water. When Atanasio returned three days later, he would discover that El Alemán had somehow moved on, taking a single roan horse with him. Unable to find El Alemán after a two-day search, Atanasio reluctantly returned north up El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro to report on the disappearance and to face interrogation by the Inquisition.

Later, the young Apache would escape, probably heading for Sonora.

The authorities dispatched a new search party to find El Alemán.

It returned empty handed.

Weeks later, a party of five traders, headed southward over that foreboding desert trail, made a grim discovery—"a roan horse tied to a tree by a halter. It was dead…" Searching, they soon discovered "hair and the remnants of clothing… …the skull, three ribs, two long bones, and two other little bones which had been gnawed by animals." The traders suspected murder, but no one would ever know for sure, but the Inquisition had claimed another victim.

Bernardo Gruber and the Jornada del Muerto

Bernardo Gruber's death gave rise to the name of that 90-mile passage: the Jornada

del Muerto, or the Dead Man's Journey. He bestowed the name "El Alemán," or "The

German," at the site of his death. With the passing centuries, the Jornada

del Muerto, marked by the graves along its length, became the most notorious

passage on the entire 1,700-mile-long Camino Real de Tierra Adentro.

The Jornada del Muerto Today

The Jornada del Muerto extends some 90 miles northward from the vicinity of the

ruins of Fort Selden, a New Mexico state monument, built in 1865, to the vicinity

of the ruins of Fort Craig, a national historic site, built in 1854. It lies

east of the Caballo and Fra Cristobal mountains, which lie along the eastern

banks of the Río Grande. The Jornada del Muerto ranks among the most pristine

segments of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro in the United States. You can still

see the route, marked by desert shrubs, from the air.

If you wish to experience something of the isolation and the harshness of the desert route followed by so many travelers over a period of nearly three centuries, you can follow a dirt road that parallels or overlays about half the Jornada del Muerto, traveling southward from the hamlet of Engle, located about 15 to 20 miles east of Truth or Consequences, at the end of State Highway 51. You will find some directions in Hal Jackson's book Following the Royal Road: A Guide to the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. You should also rely on the U.S. Geological Survey maps for the area.

by Jay W Sharp

More on the trail

NPS PDF

National Park Service overview.

BLM Dead Man's Journey Trail Dedication

More Trails

Desert Trails

Trails of the Native Americans

Coronado Expedition from Compostela to Cibola

Coronado Expedition from Cibola to Quivira then Home

Chihuahua Trail

Chihuahua Trail 2

The Juan Bautista De Anza Trail

Santa Fe Trail

The Long Walk Trail of the Navajos

The Desert Route to California

Bradshaw's Desert Trail to Gold

A Soldier's View of the Trails Part 1

A Soldier's View of the Trails Part 2

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms

Click here to see current desert temperatures!