The Santa Fe Trail

Kit Carson

Christopher "Kit" Carson played an almost legendary role in the exploration and settlement of the American West, from its thorny deserts to its forested mountain slopes to its grassy prairielands. He defined a noble vision of the American frontiersman and became an icon of American heroism, the embodiment of courage, grace, self reliance, savvy, daring, fairness and modesty.

Kit Carson with Beaver Hat

By Unknown photographer - http://www.sandiegohistory.org/journal/v49-1/warimages.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35904566

Carson invested his legacy, not only in the 19th century West, but also on the Santa Fe Trail—that avenue of commerce, conquest and opportunity which connected Missouri and America to the Southwest and Mexico’s northern Chihuahua.

The Trail

When the Santa Fe Trail first opened, in 1821, it began at a village and landing area called Franklin, on the north bank of the Missouri River in the central part of the state of Missouri. It headed west, following the Missouri upstream, across tall grass prairie, to the bend where the river turns sharply to the north. The trail continued on to the west, across the heart of Kansas and through increasingly more elevated, more arid lands. It passed through the site of Council Grove, where the tall grass prairie melted into the mixed grass prairie, and the vicinity of Dodge City, where the mixed grass prairie dissolved into the short grass prairie.

Arrival of the caravan at Santa Fe, lithograph published c.1844 - By Unknown author - http://digitalnm.unm.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/acpa&CISOPTR=647&CISOBOX=1&REC=3, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15640908

Arrival of the caravan at Santa Fe, lithograph published c.1844 - By Unknown author - http://digitalnm.unm.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/acpa&CISOPTR=647&CISOBOX=1&REC=3, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15640908From the center of Kansas, the Santa Fe Trail’s "Mountain Branch" followed the north bank of the valley of the Arkansas River upstream, westward across the rolling prairie lands of southeastern Colorado, where the plants and the terrain began to speak of desert basins and mountain ranges. At the site of today’s La Junta, Colorado, several miles upstream from where Charles Bent, William Bent and Ceran St. Vrain would build their famous Fort Bent trading post in 1833, the trail crossed the Arkansas river and turned southwest, bringing into view the Southern Rocky Mountains on the western horizon. It crossed from Colorado into New Mexico through the torturous Raton Pass, at an elevation of nearly 8000 feet above sea level. It continued generally south, along the eastern foothills of the Sangre de Cristo and Santa Fe mountains, passing peaks as high as 12,000 feet above sea level.

Alternatively, from the center of Kansas, the trail’s arid and Indian-threatened but much shorter "Cimarron Cutoff" veered away from the valley of the Arkansas River, heading to the southwest corner of Kansas and crossing over the southeastern tip of Colorado and the northwestern corner of the Oklahoma Panhandle into New Mexico. The Mountain Branch and Cimarron Cutoff rejoined on the eastern flanks of the Sangre de Cristo mountains.

The trail turned west northwest near the southern end of the Rocky Mountains, passing the Pecos Pueblo (once a major Indian trading center) and crossing Glorietta Pass (an important Civil War battle site). It ended in Santa Fe, at the plaza before the Mexican administrative building called the "Governor’s Palace," where it connected with the 550-mile-long Chihuahua Trail, the route to the settlements and markets of northern Chihuahua.

As years passed, the beginning of the Santa Fe Trail moved 100 miles upstream, from Franklin to the great bend of the Missouri and the newly founded communities of Independence and Westport (now part of Kansas City). As traffic increased, the trail evolved to include new branches, bypasses and intersections to meet the purposes of its travelers.

As years passed, the beginning of the Santa Fe Trail moved 100 miles upstream, from Franklin to the great bend of the Missouri and the newly founded communities of Independence and Westport (now part of Kansas City). As traffic increased, the trail evolved to include new branches, bypasses and intersections to meet the purposes of its travelers.

From Independence, the Santa Fe Trail, which lasted from the time of William Becknell’s trade expedition in 1821 to the coming of the railroad in the 1870’s, extended roughly 900 miles by the Mountain Branch route and approximately 800 miles by the Cimarron Cutoff route. In the plains, it passed through the ranges of the Osage, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kaw, Comanche and Kiowa—all fearsome war-making peoples of the Southern Plains. In southeastern Colorado and northeastern New Mexico, it passed through the lands of the Utes and the Jicarilla Apaches, both combative tribes of the Southern Rockies.

By its end, the Santa Fe Trail had become the gateway to adventure for Kit Carson and many other frontier personalities and one of the most storied roadways of the frontier American West.

Map provided by Santa Fe National Historic Trail - NPS

Kit Carson Looks West

Kit Carson, born in Kentucky on Christmas Eve, 1809, grew up in Franklin, Missouri, fired by the tales of those who had traveled the Santa Fe Trail. An impoverished and illiterate teenager, he took up an apprenticeship with a saddle maker named David Workman. Two years later, drawn by the siren call of the West, he decided he would leave his apprenticeship, as he recounted in his book Kit Carson’s Autobiography (a heavily edited transcription of Carson’s actual words). Workman "was a good man… But taking into consideration that if I remained with him and served my apprenticeship, I would have to pass my life in labor that was distasteful to me, and being anxious to travel for the purpose of seeing different countries, I concluded to join the first [Santa Fe Trail] party that started for the Rocky Mountains."

In August of 1826, the opportunity came. Carson ran away from home and employer. He joined a trade caravan led by Charles Bent, a co-founder of Bent’s Fort and an important figure in Carson’s future. He set out to see "different countries." In all likelihood, neither Carson nor Bent ever knew about the notice his employer posted in the Missouri Intelligencer:

Notice is hereby given to all persons,

That Christopher Carson, a boy about 16 years old, small of his age, but thick-set; light hair, ran away from the subscriber, living in Franklin, Howard County, Missouri, to whom he had been bound to learn the saddler’s trade, on or about the first of September last. He is supposed to have made his way to the upper part of the state. All persons are notified not to harbor, support, or assist said boy under the penalty of the law. One cent reward will be given to any person who will bring back the said boy.

Franklin, Oct. 6, 1826.

David Workman

If we can judge by the reward money, even in terms of its value in 1826, Workman apparently had little interest in recovering his young apprentice.

In his trip over the Santa Fe Trail, young Carson soon came face to face with the harsh reality of the frontier. "On the road," he said, "one of the party, Andrew Broadus, met with a serious accident. He was taking his rifle out of a wagon for the purpose of shooting a wolf and, in drawing it out, accidentally discharged it, receiving the contents in the right arm. We had no medical man with us, and he suffered greatly from the effects of the wound. His arm began to mortify and we all were aware that amputation was necessary. One of the party stated that he could do it. Broadus was prepared for any experiment that could be of service to him. The doctor set to work and cut the flesh with a razor and sawed the bone with an old saw. The arteries being cut, to stop the bleeding, he heated a kingbolt from one of the wagons and burned the affected parts, and then applied a plaster of tar taken off the wheel of a wagon. The patient became perfectly well before our arrival in New Mexico."

Kit Carson Makes his Name

From Santa Fe, Carson headed 70 miles to the north, to Taos, the place he always would always come back to after his journeys. He "passed the winter of 1826-7, at the house of a retired mountaineer," according to Charles Burdett in The Life of Kit Carson. "And it was while residing there, that he acquired that thorough familiarity with the Spanish language, which, in after years, proved of such essential service to him." Although illiterate, Carson clearly had a gift for languages. In addition to Spanish, said Thomas Edwin Farish in his History of Arizona, Volume I, Carson learned French from French-Canadian trappers, and he learned eight or nine Indian languages from various tribes.

Over the next couple of years, Carson, driven by a relentlessly restless spirit, worked as an interpreter for a trade caravan which traveled the Chihuahua Trail, from Santa Fe to Chihuahua City. He worked as a cook for a trapper and fur trader who lived in Taos. He worked as a teamster at the copper mines on the Gila River, in the Sonoran Desert. "Not satisfied with this employment, I took my discharge and departed for Taos, where I arrived in August [1829]," he said in his autobiography.

Over the next dozen years, Kit Carson trapped beaver, sold furs and fought Indians across the Southwestern desert basin and range country, the Pacific Coast states and the Rocky Mountains. He worked as a hunter for his old friend, Charles Bent, supplying meat for Bent’s Fort, which had become an important post on the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail. And he became the quintessential "mountain man." Burdett said that "Carson’s curiosity, as well as care to preserve the knowledge for future use, led him to note in memory, every feature of the wild landscape, its mountain chains, its desert prairies…"

In the spring of 1842, during a trip which took him over the Santa Fe Trail, he met, by chance, a young U. S. Army officer named John C. Fremont. He learned that, under orders from Washington, Fremont had set out to organize an expedition to survey the Rockies in Wyoming, in the vicinity of South Pass, the 7550-foot high and 20-mile-wide mountain crossing for the budding Oregon Trail. Fremont needed a guide.

"I told Colonel Fremont that I had been some time in the mountains and thought I could guide him to any point he would wish to go," said Carson in his autobiography. He could also speak to a number of the Indian tribes in their own languages.

"I was pleased with him and his manner of address at this first meeting," said Fremont in his autobiography, Memoirs of My Life. "He was a man of medium height, broad-shouldered and deep-chested, with a clear steady blue eye and frank speech and address; quiet and unassuming."

The two men soon forged a bond. "And now Carson’s life… commenced in earnest," said Burdett, for heretofore he has only been fitting himself to live." Between 1842 and 1847, Carson guided Fremont’s exploratory expeditions to South Pass, the Great Salt Lake, the Northwest and California, playing a key role in opening the West to immigrants from the United States. When the Mexican War erupted during the middle of Fremont’s last expedition, drawing that officer’s forces into battle, Carson fought in the conflicts at San Pasqual, San Miguel and Los Angeles. He emerged from the Fremont expeditions as a celebrated national hero, feted by President James K. Polk and senators in Washington, primarily because of Fremont’s reports about his service to the country. Pulp fiction writers began to feature a "Kit Carson" in their dime-store novels.

Carson Settles Down?

After the Mexican War, Carson returned to northern New Mexico, Taos, starting to think seriously about settling down. Speaking of his trapping and hunting days, he said, wistfully, that "I had…been in the mountains sixteen years, passing the greater part of my time far from the habitations of civilized man, and with no other food than that which I could procure with my rifle. Once a year, perhaps, I could enjoy the luxury of a meal consisting of bread, meat, sugar and coffee."

Then, "In April, 1849, Mr. Maxwell [Lucien B., a long-time companion of the trails] and I concluded to make a settlement at the Rayado [a river-valley site on the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail, east of New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains]. We felt that we had been leading a roving life long enough and that now, if ever, was the time to make a home for ourselves… We were getting old and could not expect much longer to continue able to gain a livelihood as we had been doing for many years. So we went to Rayado, where we commenced building and making other improvements, and were soon started on the way to prosperity." Maxwell would capitalize on his family connections and towering ambitions to become a land baron and a major force in northeastern New Mexico.

Carson’s thoughts of settling down may have been influenced by a lovely 15-year-old Mexican girl named Josepha Jaramillo, Charles Bent’s sister-in-law. Carson had married Josepha in 1843, after experiencing the pain of losing two earlier wives. First, according to Stephen Chinn’s "Family History of Kit Carson," posted on the Kansas Heritage Server internet site, Carson had married a 16-year-old Arapahoe girl named Singing Wind in 1835. He lost her in 1838, soon after she gave birth to their daughter, Adaline. He had married a 17-year-old Cheyenne girl named Making-Out-Road in 1840. He lost her when she abandoned him to follow her people in a tribal migration. He would stay married to Josepha for some 25 years, fathering eight children before her death in 1868.

Even with a beautiful young wife, a growing family and advancing age, Carson wore the mantle of home life uncomfortably. Even after he "concluded to make a settlement" because he "had been leading a roving life long enough" and was "getting old," he led survey and exploratory expeditions into the Rocky Mountains. He ran down outlaws and renegade Indians for the Army. He served as an Indian Agent for the U. S. Government. He drove 6500 sheep from New Mexico to market in California. He commanded the Union’s First New Mexico Volunteer Regiment in the bloody Civil War battle at Val Verde, on the Rio Grande in central New Mexico. Under orders from the Indian-hating Major General James H. Carleton, he broke the back of Mescalero Apache resistance in southeastern New Mexico’s Sacramento Mountains, forcing the tribe into imprisonment at the dreary Bosque Redondo on New Mexico’s Pecos River. He brought the Navajos to their knees in a scorched earth winter campaign in northeastern Arizona, forcing them into imprisonment with the Mescaleros at the Bosque Redondo.

The Santa Fe Trail Connection Revived

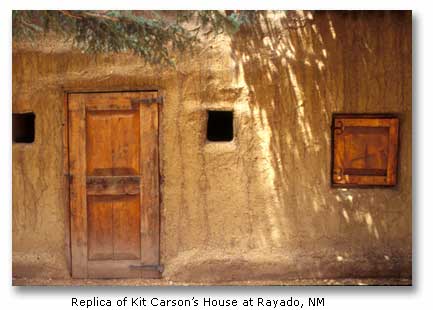

In the meantime, Carson revived his long-time connection to the Santa Fe Trail at Rayado, the earliest settlement and headquarters in Maxwell’s emerging northeast New Mexico empire, the 3000-square mile Maxwell Land Grant. Carson built a modest home for his family and himself near the Maxwell complex. He began the process of settling down. At least, Kit Carson’s version of settling down.

Kit Carson Museum, Rayado, New Mexico - By Kermit Murray - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34876831

Soon, "In the vicinity of the home of Carson, and that of his friend Maxwell, [were] gathered a number of their old comrades—men of the mountains…" said Burdett. According to F. Stanley in his book The Grant That Maxwell Bought, they called their community "Rayado," the Spanish word for "streaks," an allusion to a local (perhaps mythical) old Ute chief who lived like a reclusive monk and painted streaks across his face. A virtual fortress, Rayado became an important stop for travelers on the Santa Fe Trail, serving both merchant caravans and stage coaches. It became a center for ranching and farming, supplying regional military garrisons, the Utes and the Jicarilla as well as commercial markets. It became a crossroads, said Stanley, for "Indian Agents, merchants, Santa Fe traders, Utes, Jicarillas, outlaws, ranchers, soldiers and Indian scouts." And, according to Stanley, it became a frequent battleground. "Many was the time the little mite of a girl [one of the settlement children] was closeted against the sudden raids of the perpetual Indians who were interested in carrying her off to be sold to Navajos as a slave and the reasonable price of five dollars."

Although the Carson home "was poverty-stricken by way of comparison" with Maxwell’s "tremendous" home, according to Stanley, his children discovered the magic of the wilderness. "…a young Carson has lassoed a little grizzly, while antelope and young fawn feed from his sister’s fingers," said Burdett. Carson, however, could not "tarry at his pleasant home much more than to care for its necessary superintendence, for his life [was] the property of the public."

In the fall of the year of his arrival at Rayado, Carson received word that a band of nearly 100 Jicarilla Apaches had attacked Santa Fe Trail merchant Mr. James M. White and a small party, including his family, near Point of Rocks, on the Cimarron Cutoff about 45 miles east of Rayado. According to David Dary in his book The Santa Fe Trail – Its History, Legends, and Lore, the Indians massacred White and the other men. They took White’s wife, daughter and a black woman slave as captives.

Carson promptly joined a rescue party, commanded by Major William N. Grier, First U. S. Dragoons, as a guide. From the massacre site near Point of Rocks, "We tracked them for ten or twelve days over the most difficult trail that I have ever followed…" said Carson in his autobiography. "We finally came in view of the Indian camp. I was in the advance, and at once started for it, calling to our men to come on. The commanding officer ordered a halt…" He intended to "parley" with the Indians. While the rescue party hesitated, the Jicarillas scattered like flushed quail. Grier ordered a charge, but too late. "At a distance of about 200 yards," said Carson, the body of Mrs. White was found, still perfectly warm. She had been shot through the heart with an arrow not more than five minutes before. …it was apparent that she was endeavoring to make her escape when she received the fatal shot." According to Dary, Mrs. White’s child and the black woman simply vanished. They were never seen again.

"I am certain that if the Indians had been charged immediately on our arrival, [Mrs. White] would have been saved… However, the treatment she had received…was so brutal and horrible that she could not possibly have lived very long." The rescue party pursued the Indians for several miles, killing one warrior, taking several animals, and capturing "all their baggage and camp equipage."

"We found a book in the camp, the first of the kind I had ever seen, in which I was represented as a great hero, slaying Indians by the hundred. I have often thought that Mrs. White must have read it, and knowing that I lived nearby, must have prayed for my appearance in order that she might be saved. I did come, but I lacked the power to persuade those that were in command over me to follow my plan for her rescue."

Over the next year, Carson led parties to hunt down Indians who had stolen livestock from Rayado. He led a military force to arrest a man who planned to murder and rob two wealthy merchants on the trail.

In March, 1851, Carson left Rayado to cross the Santa Fe Trail with twelve wagons "belonging to Mr. Maxwell…for the purpose of bringing back goods for him." During his return with his freight, Carson ran into a band of Cheyenne on the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail, in southeastern Colorado. He did not know that the Cheyenne had come with the intent of avenging an American officer’s flogging of one of their chiefs. He thought they came as friends. He invited them to sit and smoke and talk. He watched as they begin to speak among themselves in their own language, unaware that he understood every word they said. He felt stunned when he learned that the Cheyenne planned to massacre him and his party.

"I was alarmed by this talk…" said Carson. "I told the Indians [in their own language, according to Burdett] that I was ignorant of the cause of their wishing my scalp, and that I had done them no injury and had wanted to treat them kindly; they had come to me as friends, but I now discovered that they wished to kill me and they must leave my camp; any who refused would be shot… They departed…," certainly shocked by Carson’s command of their language.

Carson moved on with his caravan, his men ready with their rifles, and when night fell, he dispatched a courier under the cover of the darkness to summon help. When the Cheyenne threatened the party again, Carson told the Indians that he had already called for military aid. He told them that "If I were killed, they [the military force] would know by whom it was done, and my death would be avenged." Fearing the military might, the Cheyenne allowed Carson and his party to pass.

Several years after he established his home at Rayado, Carson sold out and moved his family back to Taos, according to Stanley, possibly because he knew that Josepha felt lonely at the Santa Fe Trail outpost and longed for her relatives and friends.

Fort Nichols

In the summer of 1865, Carson, by then a colonel in rank, carried out one of his last assignments on the Santa Fe Trail. In command of 300 troopers – the U. S. Volunteers – he oversaw the construction of Fort Nichols on the Oklahoma segment of the Cimarron Cutoff, where it would be charged with protecting caravans and stages from predatory Indians and outlaws. "It was about 140 miles northeast from Fort Union—was a desert halfway station upon the route of 300 miles between Fort Union and the Cimarron Crossing of the Arkansas," said Edwin L. Sabin in his Kit Carson Days, 1809 - 1868.

"The country hereabouts was familiar to him. It had its memories. He had first crossed it thirty-nine years back, or in 1826, when he was a runaway boy of 16, with that Santa Fe caravan from Missouri. He had crossed it and recrossed it. As an outcome of a generation of events he was here again…"

While at Camp Nichols, Carson was suffering from the long-term effects of severe internal injuries he had received five years earlier, when a horse had fallen with him in the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado. He had become entangled in the lead rope and "dragged along and badly punished," according to Sabin. The accident left him with a "pain in the chest, a tendency to cough, and a feeling of suffocation when he was lying flat."

"Colonel Carson did not seem extra well those days at Camp Nickols [sic]," said Marian Russell in her memoirs, Land of Enchantment. Marian, the new bride of Richard Russell, one of Carson’s young officers, and the only woman at Camp Nichols, had idolized Carson since her childhood. She fretted about his health. "I think the army rations did not agree with him. Some days his face seemed haggard and drawn with pain."

Although concerned for her safety, Carson had allowed Marian to come to Camp Nichols in June of 1865, escorting her and her husband from Fort Union. Along the trail, "Colonel Carson, his mind on the Indian atrocities, kept pointing out places where some disaster had occurred. When we came to the crossing of White’s Creek [near Point of Rocks] he had me dismount and stand by a heap of stones with him. It was here that Indians attacked the wagon train which the White family traveled."

At moments during the construction of the fort, Carson showed his old spunk. "One night a great thunderstorm came up," said Marian. "I had never known the wind to blow so hard. It came fitfully and in a circular motion. At intervals the lightning would tear jagged holes in the black sky and our tent with be illuminated with an unearthly blue light. Suddenly our tent pole buckled. I hid my head under Richard’s arm and did not hear Colonel Carson calling. Richard was trying to find his clothing when the Colonel’s cry changed suddenly into a roar of rage. His tent had fallen down up on him. Richard had to call out the Corporal of the guards to get the Colonel extricated."

Declining health and powerful thunderstorms notwithstanding, Carson got Fort Nichols built. "Little Camp Nickols became in a jiffy as impregnable as an old castle," said Marian. "It was surrounded by rock walls and a deep ditch or moat. Inside the rock walls the houses were half-dugouts four feet under ground and four foot rock walls above ground… Mounted howitzers were placed along the walls."

Then, said Marian, "One morning the Colonel came leading his big black horse by the bridle. ‘Little Maid Marian,’ he said, ‘I have come to say Good-bye.’ His last words to me as he rode away were, ‘Now remember the Injuns will git ye if you don’t watch out.’ I watched him as he rode away. The picket on the western lookout arose as he passed and saluted. The black horse mingled with mirage on the horizon and thus it was that Kit Carson rode out of my life forever."

Kit Carson died on May 23, 1868, in Fort Lyon, Colorado, one month after the death of his beloved Josepha.

In the four decades between 1826, the year young Kit Carson ran away from home, and the late 1860’s, the last years he traveled the Santa Fe Trail, he saw – and sometimes helped drive – powerful currents of change between the grassy plains of Missouri and Kansas and the desert basin and mountain range country of the Southwest. He saw the traffic change from small, occasional makeshift caravans of reconditioned and reinforced wagons, carts and carriages in the early days to frequent fleets of the great freight wagons called "prairie schooners" or "Conestogas" in the later days. He saw the purpose expand from mere commerce to include warfare, migration, plunder and treasure seeking. He saw the travelers of the trail evolve to include not only merchants but also raiders, soldiers, emigrants, miners, outlaws and adventurers. He had to know that the railroad had reached Kansas, headed for Colorado and New Mexico, signaling the end of the Santa Fe Trail and the close of an era.

More Trails

Desert Trails

Trails of the Native Americans

Coronado Expedition from Compostela to Cibola

Coronado Expedition from Cibola to Quivira then Home

Chihuahua Trail

Chihuahua Trail 2

The Juan Bautista De Anza Trail

Jornada del Muerto Trail

The Long Walk Trail of the Navajos

The Desert Route to California

Bradshaw's Desert Trail to Gold

A Soldier's view of the Trails Part 1

A Soldier's view of the Trails Part 2

Related DesertUSA Pages

- How to Turn Your Smartphone into a Survival Tool

- 26 Tips for Surviving in the Desert

- Your GPS Navigation Systems

May Get You Killed

- 7 Smartphone Apps to Improve Your Camping Experience

- Desert Survival Skills

- Successful Search & Rescue Missions with Happy Endings

- How to Keep Ice Cold in the Desert

- Desert

Survival Tips for Horse and Rider

- Preparing

an Emergency Survival Kit

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms