Trails of the Native Americans

Passageways

"In the New World," said Carl Sauer in his 1932 monograph The Road to Cibola, "the routes of great explorations usually have become historic highways and thus has been forged a link connecting the distant past with the modern present. For the explorers followed main trails beaten by many generations of Indian travel."

Major Native American Trails

For thousands of years, Native Americans took to the trails in the name of the harvest, the hunt, commerce, plunder, warfare, religious fervor and celebration. They may have forged trails at least as far back as some eight or nine millennia ago, when Archaic Indian peoples likely began to follow regular seasonal circuits to harvest the ripening seeds, nuts and fruits of wild plants and to hunt migrating game of the basins and plains. As populations grew and cultures evolved over time, the Native Americans forged thousands of miles of interconnecting trails extending from Texas’ Llano Estacado westward to California’s Pacific Coast and from Mexico northward across the Southwest.

They left the remnants of their commodities at settlements along their route. They left debris such as broken ceramic pots and fractured stone tools scattered along the trails much as modern travelers leave aluminum and plastic soft drink containers strewn along super highways. Sometimes, Native American travelers – products of the spirituality of their cultures – left shrines beside the trails and carved or painted images on nearby stone surfaces.

Table mountains on the southern edge of Llano Estacado, Texas.

By GerritR - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69779775

Major East-to-West Arteries

According to Richard I. Ford’s paper "Inter-Indian Exchange in the Southwest," published in the Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest, Volume 10, several primary east-to-west arteries began on the Llano Estacado. Leading westward, they branched and then branched again to reach the hunting and gathering tribes and the Puebloan communities of the Southern Rockies, the Colorado Plateau and the basin and range country. Ultimately, they converged at crossings at the Colorado River, one near Needles, California, and a second between Blythe, California, and Yuma, Arizona. The trail which crossed near Needles ran through the Mojave Desert and on to the Pacific Coast near Los Angeles. The one which crossed between Blythe and Yuma ran through the southern California basin and range country and on to the Pacific Coast near San Diego.

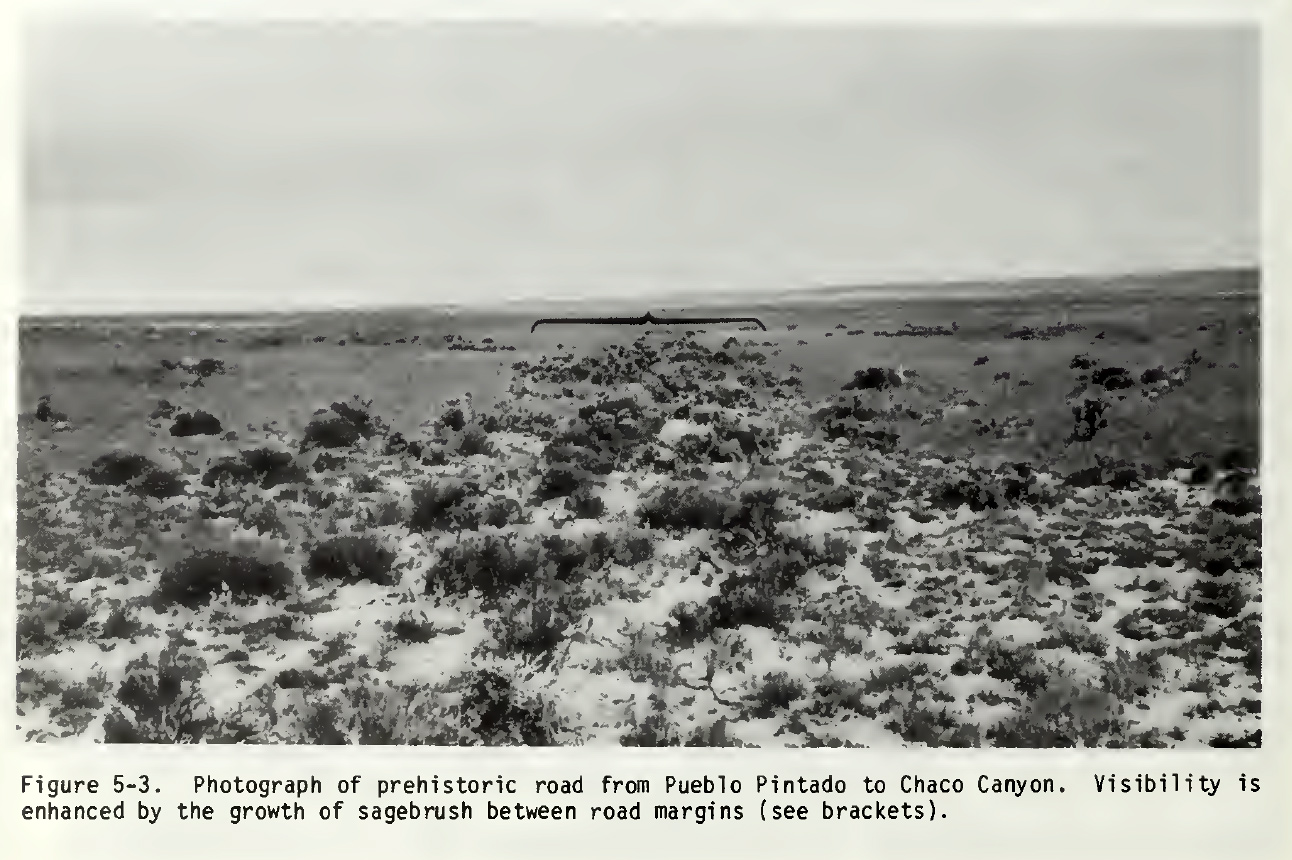

Prehistoric road. From Chaco Roads Project Phase 1, A Reappraisal of Prehistoric Roads in the San Juan Basin 1983. BLM, Chris Kincaid.

Typically, the east-to-west trails served the purpose of trade, creating, in effect, a Southwestern distribution system for the Llano Estacado’s buffalo hides and meat and the Pacific Coast’s sea shells as well as hundreds of other commodities.

Major South-to-North Trails

At least three well-documented major south-to-north arteries – or, connected segments of trails – began in Mexico.

One, nearly 1200 miles long, started west northwest of Mexico City, at Guadalajara in the Mexican state of Jalisco. According to Sauer, it led westward for about 150 miles, to the Pacific Coast. It turned north northwest, following the coastline for nearly 500 miles. It turned generally north, paralleled the western flanks of Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental, crossed the border halfway between Nogales and Douglas, and continued across Arizona to the Zuni pueblos, a leg of some 600 miles. A second south-to-north artery, 1400 to 1500 miles long, began at Mexico City. It ran generally northward for more than 1000 miles across Mexico’s central highlands and through the Chihuahuan Desert basin to the Rio Grande’s Paso del Norte crossing. It followed the river upstream for about 400 miles to the upper drainage basin. These two south-to-north trails developed as avenues for trade, in effect, conduits for macaws, colorful feathers, copper bells and other Mesoamerican goods moving north and turquoise, obsidian, buffalo hides and other Southwestern goods moving south. Over time, the travelers from the south also introduced northern tribes to various ideas of religion and ritual; crops such as corn, beans and squash; the craft of pot-making; new products from distant workshops; and different concepts in architecture.

A third important south-to-north artery, more than 500 miles long, began in northern Chihuahua and Coahuila as a fan of trails with an apex at the Rio Grande’s "Grand Indian Crossing" in Texas’ Big Bend, at the southernmost point of the national park. It ran north, through basin and range country for 140 miles, veered generally eastward for nearly 40 miles to the Pecos River and an infamous ford called "Horsehead Crossing." It turned northwest for some 50 miles, until it struck the plains. It followed the southern and then the eastern perimeter of the Llano Estacado until it reached the headwaters of the North Fork of Red River, high in the Texas Panhandle. This trail, known as the "Comanche War Trail," summoned the Comanches and Kiowas, tribes of the southern plains, not to trade, but rather to plunder Mexican villages and haciendas, primarily for horses and slaves. Over time, the warriors of the plains returned home with so much booty that the Grand Indian Crossing resembled a "very wide, well beaten, and…much traveled thoroughfare...," according to Captain John Love, who attempted to navigate the Rio Grande by flat boat in 1850.

Unexplained Trails

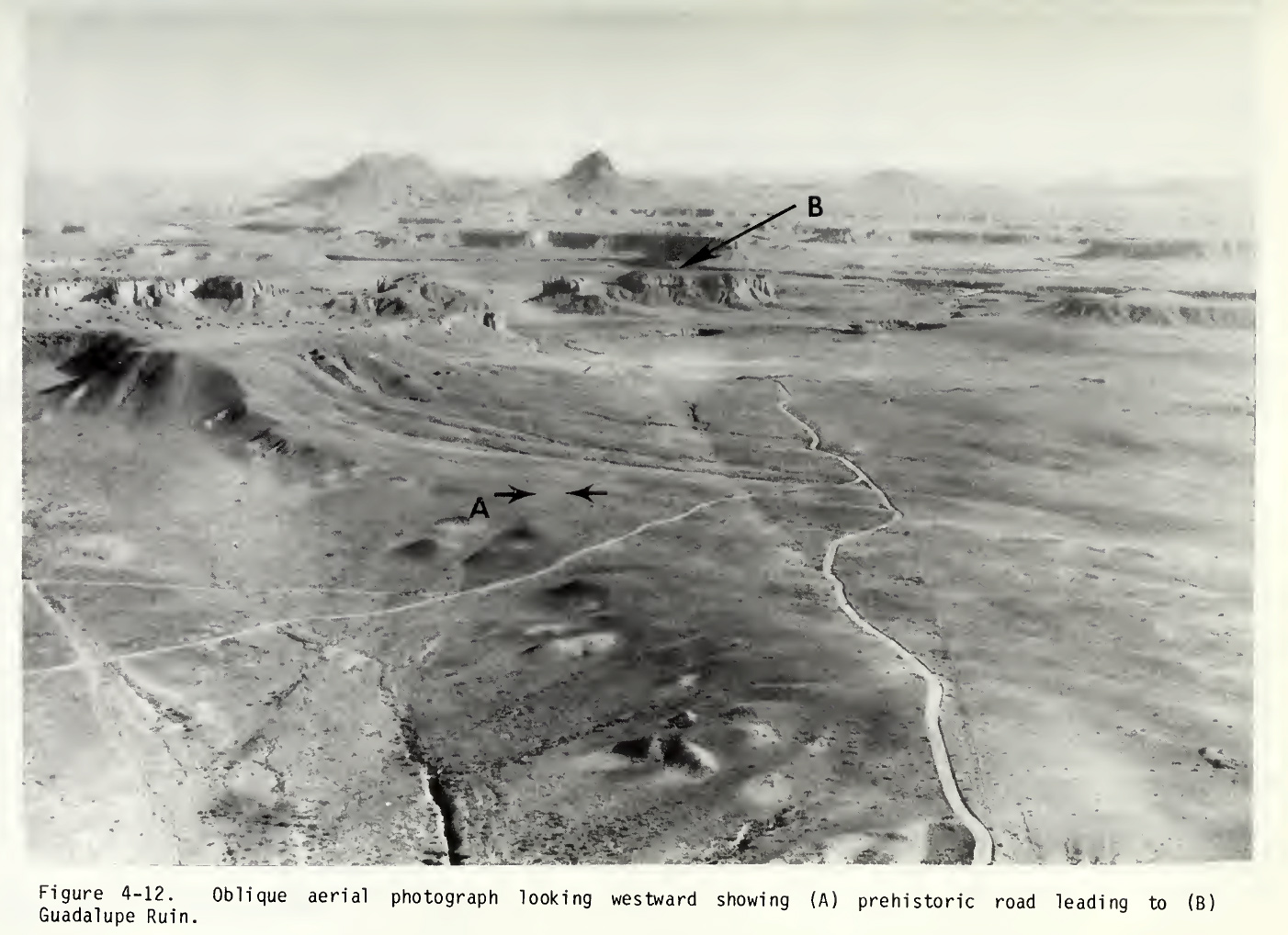

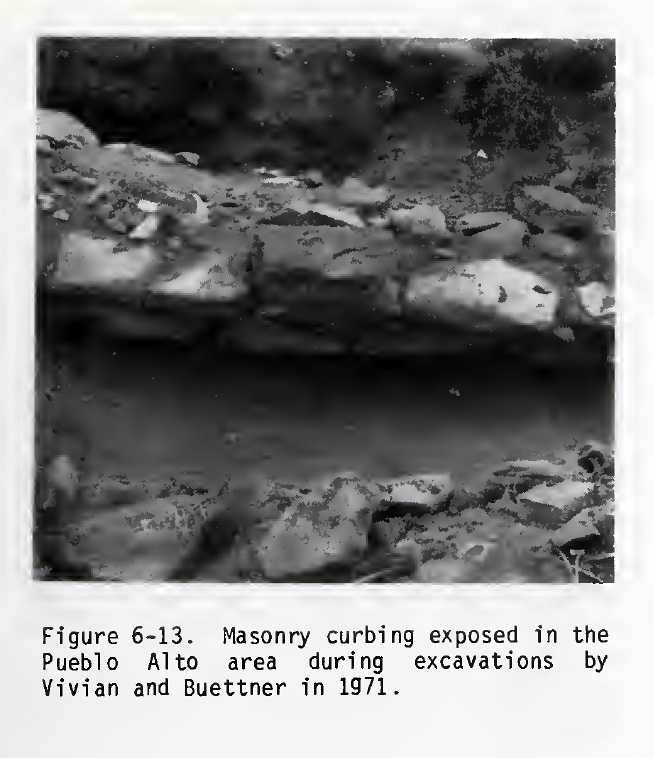

While most Native American trails clearly accommodated the traveler, others served uncertain purposes, for instance, the enigmatic 400-mile network of "roads" which radiate from the famed Chaco Canyon Anasazi Puebloan complex, the early second millennium "Rome" of northwestern New Mexico. These roads, distinguished by long straight segments, unusual width (typically 30 feet), curbing, border walls, berms and small road-side "motels," usually connected Chaco Canyon – the region’s commercial and religious capital – with outlying communities. Some ended at the canyon rim, at precipitously steep stairways to the canyon floor.

Some archaeologists think that the Chacoan communities may have used the roads to distribute crops and other goods from areas with surpluses to areas with shortfalls, although that would not appear to explain the prodigious investment of manpower required for the construction and maintenance. Others have suggested that the Chacoans used the roads as tracks for foot races or as avenues for hauling construction timbers. Neither would that seem to justify the labor investment. Others suspect that the Chacoan peoples may have constructed the roads to function effectively as "stage sets" for elaborate pilgrimage processions and celebrations. If so, the commitment to religion and ritual would seem to be extraordinary. The Chacoan road complex will likely remain one of the mysteries of Southwestern prehistory. We can only say for certain that all the roads led to Chaco.

The Native American Travelers

Before the arrival of Spanish horses, Native American travelers, wearing sandals or moccasins, walked the trails of the Southwest. They transported their burdens on their backs, atop their heads or, on the Llano Estacado, with pack or draft dogs. With the acquisition of horses, many Native Americans extended their range of travel and increased the sizes of their burdens.

Hunters and Gatherers

In treks repeated year after year, the foot-bound Archaic hunting and gathering bands may have worn early trails between seasonal campsites in a desert basin, where they harvested agaves; on a mountain slope, where they gathered pinyon pine nuts and juniper seeds; near a marsh, where they took migratory water fowl; and near the plains, where they hunted migrating buffalo.

Traders

With the emergence of settled villages of farmers, traders likely became the primary authors of the trails of the Southwest.

West Texas rock art panel showing possible traders carrying burdens.

While "Most of the trade was an indirect movement through many hands and several peoples…," as Donald D. Brand said in his paper "Prehistoric Trade in the Southwest," published in the New Mexico Business Review, October 1935, individual itinerant traders apparently traveled the trails to call on certain communities like modern traveling salesmen cover a "territory" to call on their customers. As late as 1895, itinerant traders "were still carrying on extensive short- and long-distance trade on foot…," in northwestern Mexico, said J. Charles Kelley in "The Aztatlan Mercantile System: Mobile Traders and the Northwestward Expansions of Mesoamerican Civilization," Chapter 9, in Greater Mesoamerica: The Archaeology of West and Northwest Mexico. These traders, probably following an ancient vocation, carried loads as heavy as 90 percent of their body weight for up to 30 to 40 miles a day.

Some individual traders, according to a romantic notion suggested by southwestern Colorado authority Michael Claypool, may have carried their goods in packs or burden baskets on their backs and played a flute to herald their arrival at a village. Bringing commodities of novelty, sacredness and high value as well as news, ideas and gossip from neighboring villages, the trader presumably found an enthusiastic welcome and perhaps even celebration and dance. It could be the itinerant trader – not a malformed, flute-playing mythical figure – whose images appear on the surfaces of prehistoric ceramics and stone across the Southwest and whose persona and charisma gave rise to the renowned "humped-back flute player," or Kokopelli.

Kokopelli pictograph "Cañon Pintado", ca. 850–1100 AD, Rio Blanco County, Colorado, Public Domain

Some Native American traders in Mexico and, probably, the Southwest drafted their families into the profession. For example, in an undated paper, "The Mobile Merchants of Molino," J. Charles Kelley drew on a 1933 account by Ralph L. Beals to describe a trading family from the Acaxee tribe of western Mexico: "The women," he said, "carried a large conical burden basket, using a tumpline. In the basket, from which hung deer hooves strung on canes and tinkling deer foot bones, there was a bushel of soft corn topped by plates…and spoons and above this a sleeping child wrapped in a mantle; at the baskets outer edge parrots and macaws [highly valued birds used in trade] were carried. The women carried their load up and down mountains apparently with great ease."

Likely, full Native American trading expeditions also took to the trails. In his paper "The Mesoamerican Connection: A View From the South," published in The Chichimec Sea, Mike Foster said, "…trading groups from the Chalchihuites, Casas Grandes, and west of Mexico appear to have reached well into the Southwest at a relatively early date, possibly as early as A. D. 350."

In addition to commodities, the Mesoamerican expeditions, said Foster, "…introduced a variety of traits – everything from new cultigens and technology to ideology – to the elementary evolving societies of the southwest."

As we know from historic accounts, itinerant Native American trading caravans wandered over the trails like gypsies, serving as middlemen in the prehistoric and early historic Southwest. For example, nomadic bands of Jumano Indians – probably remnants of southern New Mexico’s Mogollon Pueblo tradition, which collapsed in the 14th century – traded along trails from the piney woods of eastern Texas to the southwestern edge of the Colorado Plateau. The Jumanos, said Nancy Parrott Hickerson in her book The Jumanos: Hunters and Traders of the South Plains, "could be encountered almost anywhere in the Southwest or South Plains."

In anticipation of trade, some tribes dispatched missions to gather raw materials which could be used as commodities. Comanche and Kiowa hunting parties, for instance, hunted buffalo, which yielded highly marketable hides, jerked meat and bone tools. Pima and Papago (nomadic tribes of southern Arizona and northern Sonora) expeditions trekked to the coast of the Gulf of California to collect that valuable mineral, salt. Mimbres people – village farmers of southwestern New Mexico – mined turquoise, which held a sacred place in Mesoamerican cultures.

Other tribes produced finished products intended specifically for trade. According to Ford, the Yumans, of the western Sonoran Desert, produced leather clothing and bags for the market place. The Hopis, of northeastern Arizona, wove cotton textiles. The Jicarilla Apaches, of northern New Mexico, made wicker baskets and micaceous pottery. The Salinas Pueblos, of central New Mexico, manufactured a distinctively decorated pottery. The Jumanos, said Hickerson, made bows and arrows. Farming villages produced surplus corn, beans and squash to offer in the marketplace.

In his book Traders of the Western Morning, John Upton Terrell itemized nearly 250 trade items which fueled the commerce of the Native American trails and markets of the Southwest. They included items as diverse as gourd dishes, horn jars and grass sieves; feather robes, teeth pendants and bone earrings; stone clubs, bone fishhooks and shell scrapers; medicine bags, feathers and turtle rattles; corn, nuts and dried berries; dog saddles, hair ropes and woven cases; and arrow points, war clubs and lances.

Traders left the evidence of their commerce in the archaeological and historical records of the communities along their routes. "Wherever there are natural corridors of passage – easy mountain passes, and optimum conditions of water, fuel, and game – there archaeological reconnaissance has discovered sites with a greater than average number of exotic wares and other trade items," said Brand. "At crossings of such corridors are found the maxima [sic] of diverse cultural elements…" Primary trading centers arose, including, for instance, the Pecos Pueblo in northern New Mexico, Gran Quivera in central New Mexico, and the San Jose junction near northern Chihuahua’s Villa Ahumada.

Some communities, for instance, the Taos and Abiquiu Pueblos of northern New Mexico and Pima settlements in southern Arizona, staged trade fairs, where vendors from across the Southwest gathered to display and exchange their commodities. Their offerings included horses and slaves in northern New Mexico during Spanish colonial times. "These were…raucous affairs," said Ford, "accentuated by drunkenness, brawls, and thievery."

Other communities evidently emerged as essentially full-time market places, where merchants, traders and consumers came to bargain and trade in settings much like los mercados of Spain and Latin America or les marches of France. Paquime, the capital of northwestern Chihuahua’s late prehistoric Casas Grandes culture, served as a major market place, according to Charles C. Di Peso, the famed Southwest archaeologist who excavated almost half of the site in the mid 20th century. "The…marketplace complex was designed and zoned for commodity exchange and the surrounding structures for visual impact," he said. The marketing plaza apparently comprised trading booths, temporary living quarters and even small chapels. It percolated with trading activity. "In its pristine condition," said Di Peso, "the tract must have had made a tremendous impact…"

Although the Native American trade network of the Southwest was born of commercial purpose, those who took to the trails never forgot their spiritual roots. "Since many dangers haunted the trails," said Ford, "various supernatural precautions guided traders. Virtually every tribe had a ceremony to protect travelers before departing and a purification rite upon returning to protect the community from any bad spirits that might have accompanied the trader."

Warriors

If traders sought wealth on the trails, raiding parties pursued the fruits of plunder, the visceral thrill of battle and the rewards of personal and tribal glory. For example, the Comanches and Kiowas, those quintessential mounted warriors of the Southern Plains, rode south over the Comanche War Trail to answer their calling in raids on the settlements in the arid ranges of northern Chihuahua. On the trail, a warrior put his faith and safety in his personal "medicine," or "power;" followed the strictly prescribed choreography of the enterprise; spoke the phraseology and code words of a raiding party; faithfully obeyed the commands of his leader; and instilled horror in his human prey. He stole horses, the currency of the plains. While he massacred men and older boys, he took young women and children captive, new conscripts or trading commodities for his tribe. Returning home over the trail, he rode hard and relentlessly to avoid pursuers and reprisals, often leaving the carcasses of horses and sometimes the bodies of his captives in his wake. He left the bones of so many broken and exhausted horses at the Pecos River that the skulls of the animals gave the ford its name: Horsehead Crossing.

Pilgrims?

The travelers who followed trails such as Chaco Canyon’s strange 11th and 12th roads may have been neither traders, nor raiders, but – as some researchers suspect – pilgrims. In a brief article called "Ideological Models: Pilgrimage," published in the papers of the "virtual conference," Evaluating Models of Chaco, J. McKim Malville speculated that Chacoan peoples may have followed the roads from outlying communities to the canyon in seasonal rituals of primal pageantry. The Chacoans may have viewed the pilgrimages as a "mythic re-creation of the world and spiritual transformation of the individual…"

They may have regarded the "…north-south alignments of the north road of structures in the Canyon [as] ideological expressions of connections to the place of origin or to the stable north point of the macrocosm." Within the road system, Malville said, "…segments that were vectored from outlying communities in the approximate direction of Chaco may have symbolized the commitment of the community to the regional system." During the festivals, the Chacoans would likely take advantage of opportunities for "trade, courtship, athletic contests, and other forms of social bonding." If the Chacoans ever did, in fact, undertake pilgrimages over the roads in pursuit of a mystical renewal of body and soul, they apparently lost faith in the system and leadership within a matter of decades. They had abandoned their communities and the road system forever by the end of the 12th century.

Something of Value

Of all the commodities which traders hauled over the trails connecting the prehistoric Mesoamerican and Puebloan peoples, turquoise and the brilliantly plumed scarlet macaw ranked near the top of the list in value. In his paper, "Meridian Addendum," October 31, 2000, Colorado University archaeologist Steve Lekson said, "Mesoamerican societies were interested in southwestern turquoise; southwestern leaders were interested in Mesoamerican civilizations and their prestige goods [for instance, the colorful macaws] as ‘outside partners’" in an effort to assert and maintain political control.

"Viewed in the composite, ancient turquoise mining was very impressive," said researchers Phil C. Weigand and Garman Harbottle in their paper "The Role of Turquoises in the Ancient Mesoamerican Trade Structure," Chapter 6 in The American Southwest and Mesoamerica. "Turquoise mining was dispersed over a very broad landscape, in a rough quadrangle from the Californias to Colorado to Coahuila to Sonora." The Indians of the Southwest mined some turquoise sources intensely, "with chambered mines indicating dedicated extraction from a single outcrop," for example, at Cerrillos and Old Hachita in New Mexico and Halloron Springs in California. Some of the mines reached depths of more than 200 feet, according to the Museum of New Mexico. The Chaco Canyon communities became a major center for procuring and processing turquoise, primarily from the Cerrillos mines, and they developed the artisanship for crafting exquisite turquoise ornaments and jewelry. Prehistoric turquoise merchants and traders left their mark in the archaeological record from the Southwest "through Mesoamerica clear to the southern Maya highlands," a region where "many hundreds of thousands of pieces" have been found, said Weigand and Harbottle. Mesoamericans seem to have vested turquoise – like jade and emerald – with sacred importance, possibly because they equated its blue green hues with the fertility, abundance and prosperity promised by verdant farm crops. They incorporated Southwestern turquoise into the jewelry and clothing of the elite, symbolic decorations of skulls, offerings for the dead, mosaics for elaborate shields and tablets, the ornamentation of ceremonial masks, sacred items for ritual, and representations of deities.

Two Scarlet Macaws at the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha, Nebraska.

By en:User:Cburnett - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1235586

While the Puebloans mined, processed and worked turquoise to meet the Mesoamerican demand for the semi-precious mineral, enterprising Mesoamericans captured and exported scarlet macaws to satisfy the Puebloan yen for the three-foot-long gloriously colored bird. Reflecting the high value placed on scarlet macaws, the Puebloans went to extraordinary lengths, in the arid Southwest, to breed, raise and nurture the bird, a native of tropical riverside rain forests. They built elaborate pens and perches for the birds at Paquime, which was probably the center for macaw distribution in the Southwest. In her book Archaeology of the Southwest, 2nd Edition, investigator Linda Cordell said, "More than 300 scarlet macaw skeletons were recovered at Casas Grandes [Paquime] from parts of the site that contained pens with eggshell, perches, and grain…" In Pueblo Bonito, archaeologist George H. Pepper’s 1920 report on his excavations at the Chaco Canyon site, he reported finding 12 macaw skeletons in "Room 38," including two ritual burials of the birds. At one point in the room, he said, "…a circular cavity had been dug in the floor and in this the skeleton of a macaw was found. The hole had been carefully formed, filled with adobe, and the surface finished so that there were no evidences of its position." Nearby another macaw "had been buried in the same manner and with as great care." The Puebloan peoples memorialized scarlet macaws in imagery on stone surfaces, for instance, at Albuquerque’s West Mesa Escarpment rock art site, and on ceramic surfaces, for example, on Paquime pots and southwestern New Mexico’s Mimbres Indian bowls. They used macaw feathers to decorate ceremonial masks and sacrificed macaws to commemorate the dead. The Zuni Pueblo people had a legend, "The Origin of Raven and Macaw," according to SouthWest USA, in which a priest told those would follow the macaw that "…wherever they fly, you shall follow, and in that place there shall be everlastingly summer, and without toil, which you haven’t yet experienced, fertile fields full of food shall flourish there…"

Turquoise and macaws answered spiritual needs of those at the ends of trade routes between Mesoamerican and the Puebloan peoples. Salt, a mineral essential to good health in both human and animal populations, met the universal nutritional needs of tribes across the Southwest. It occurred in some basins which had held lakes during the Ice Ages, for instance, at the Salt Flats of western Texas, the Zuni Salt Lake in western New Mexico and the Estancia lakes in central New Mexico. From the 12th through the 17th centuries, the Salinas Puebloan people harvested and traded salt from the Estancia lakes. (The term "salinas," conferred by the Spanish, means "salt works" in English.) In 1601, Spanish soldiers, realizing the importance of the Estancia salt, slaughtered some 900 Puebloans to beat back a challenge for control of the lakes, said Robert Silverberg in his book The Pueblo Revolt.

Slaves, an unwilling but perhaps the most valued commodity of the trade from the 17th through the 19th centuries, played featured roles in a sordid chapter which lasted at least from the time of Spanish arrival to the years just after the American Civil War. The Utes, for instance, made commerce in slaves a major part of their economy, hauling captives to the Taos Pueblo and Santa Fe to swap them for horses and other commodities. The Navajos paid a particularly painful price, perhaps the most of any Native American tribe in the Southwest. In a quote published in Raymond F. Locke’s, The Book of the Navajo, old-time Santa Fe resident Dr. Louis Kennon said, "I think that the Navajos have been the most abused people on the continent… [I believe] the number of Captive Navajo Indians held as slaves to be underestimated. I think there are from five to six thousand. I know of no [New Mexico] family which can raise one hundred and fifty dollars but what purchases a Navajo slave, and many families own four or five, the trade in them being as regular as the trade in pigs and sheep…" Even as the Civil War wound down in the east, General James Henry Carleton, commanding officer of New Mexico, promoted the slave trade as a way of dealing with the Indians in the Southwest.

Some of the trails of the Native Americans of the Southwest

Following the Trails

As you would anticipate, most Native American trails have faded or disappeared, largely obliterated by highways, development, the plow, excessive livestock grazing and abandonment. You can, however, still visit some passages, river crossings and Puebloan trade centers.

Up the Rio Grande to the Pueblos

From the ancient Paso del Norte ford, you can travel up the Rio Grande for nearly 400 miles, following, with reasonable closeness, the northern reaches of the trail which began in Mexico City and ended in the northern river basin pueblos. You will track one of the most historic roadways in the United States, following the paths, not only of prehistoric Native American traders, but also of conquistadores, colonists, soldiers, Franciscan friars, refugees, merchants and railroad barons.

If you begin at the ford, located just off Doniphan Street immediately west of downtown El Paso, Texas, and just across the river from Mexico’s teeming Juarez, Chihuahua, you’ll find the 1850 flour mill of Simeon Hart, a historic cemetery of the local community, the 1881 headquarters of Fort Bliss, and the 1881 location of a railroad passenger and freight terminal. Unfortunately, the ford and the historic sites lie in the midst of a sadly dilapidated area where the United States Border Patrol struggles to turn back the tide of illegal immigrants, petty criminals and drug runners who would now make the historic crossing their own.

From El Paso, you will follow IH 10 for 40 miles to Las Cruces, IH 25 for 220 miles to Albuquerque, IH 25 and US 84 for 60 miles to Santa Fe, and US 84 and NM 68 for 70 miles to Taos. If you can look beyond the profound alterations we have made along the river in historic times, you will see the Chihuahuan Desert Rio Grande basin country and the mountain ranges through which the prehistoric traders traveled, on foot, between El Paso and Albuquerque. Like the foot-bound traders, you will see the Sangre de Cristo mountains rise on the northeastern horizon as you draw near Santa Fe. You will follow the eastern flank of the Sangre de Cristo mountains and, for 30 miles, the dramatic Rio Grande gorge as you approach Taos.

Traders who made the trek around the year 1200 would have encountered pueblo villages scattered along virtually their whole route up the river. If they had repeated the trip about 1450, they would have passed abandoned pueblos until they reached the Piro- and Tompiro-speaking pueblos about 160 or 170 miles north of the Paso del Norte ford. Of the 100 or more pueblos occupied in late prehistoric times, Taos, founded roughly nine centuries ago, remains as one of only 18 pueblos still occupied today.

Puebloan Trade Centers

Based on the archaeological record, it appears that main trunk lines or branches of trails connected many of the Southwestern pueblos to a trade network, which grew and contracted and changed continuously over time like something alive. Some pueblos became important centers of trade, giving definition to their character.

If you enjoy trips outside the tourist mainstream, I would suggest that you spend a couple of days exploring the ruins of central New Mexico’s 12th to 17th century Salinas trade center pueblos, Abo, Quarai and Gran Quivira (collectively, a national monument). Located in basin and range country on the border between the Puebloan world to the north and west and nomadic hunting and gathering populations to the south and east, the Salinas Pueblos became natural centers for trade and an apparent linchpin in the Jumano commercial enterprises.

Salinas artisans produced a pottery called Chupadera Black-on-white, which – possibly thanks to the Jumano trading caravans – has turned up in Native American archaeological sites from the Piney Woods of east Texas to desert lands of northwestern Chihuahua and southeastern Arizona. Salinas workmen collected and packaged salt from the Estancia lakes, delivering it as a commodity into the trade network. Like other pueblos, Abo, one of the region’s most populous communities, experienced the destruction of its ceremonial chambers and icons by Spanish priests, who were obsessed with the idea of converting the Native Americans to Catholicism.

It was Quarai, according to Silverberg, that suffered the loss of the 900 people in the 1601 fight with the Spanish over control of the Estancia lakes. Gran Quivira hosted the renowned Spanish Franciscan frontier priest Alonso de Benavides, who preached to the Puebloan population in the plaza immediately in front of the church in 1626. The Puebloans and their Spanish friars abandoned Abo, Quarai and Gran Quivira around 1670 under incessant raiding by the Mescalero Apaches, who had been enraged by Spanish slaving expeditions. The Salinas Pueblos lie about 50 miles south southeast of Albuquerque, surrounding a little village by the name of Mountainair.

I would also recommend that you visit the 12th to 19th century Pecos Pueblo, another national monument, located in a mountain corridor at the southern end of the Sangre de Cristo range. Pecos emerged as a trading center – a commercial "middleman" – because of its location at the juncture between the pueblos to the west and the Plains Indians to the east. It functioned as "a two-way pass for barter and war between Pueblos and Plains tribes," according to historian Herbert Eugene Bolton, quoted in Pecos: Gateway to Pueblo & Plains – The Anthology. Located on a bluff overlooking a shallow valley which served as a marketplace, Pecos received Pedro de Castaneda, soldier and chronicler of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado’s epic expedition, in 1541.

The Spaniard described the pueblo as "square, situated on a rock, with a large court or yard in the middle, containing the estufas [semi-subterranean ceremonial chambers called "kivas"]. The houses are all alike, four stories high. One can go over the top of the whole village without there being a street to hinder. There are corridors going all around it at the first two stories… The houses do not have doors below, but they use ladders, which can be lifted up like a drawbridge… As the doors of the houses open on the corridor of that story, the corridor serves as a street… The village is enclosed by a low wall of stone…" Pecos, abandoned about 1840 because of internal disputes, Comanche hostilities, and epidemic diseases, is located about 20 miles southeast of Santa Fe.

You should not miss Taos, even though the pueblo has been rebuilt during historic times. (The ruins of the original village lie a few hundred yards to the west, according to Bolton.) In the 13th century, Taos hosted trade fairs which drew Native American peoples up the trails, not only from other pueblos, but from the Southern Plains, the Navajo and Apache ranges and northern Mexico as well. By the 18th century, Taos staged even larger trade fairs, including a lively slave market, attended by the Indians and by fur trappers and Spanish- and English-speaking merchants. For the sake and duration of the fairs, Taos managed to foster a truce across a region which was often the scene of raids and warfare. "At this village," said Castaneda, "they [the Spaniards] saw the largest and finest hot rooms or estufas that there were in the entire country, for they had a dozen pillars, each one of which was twice as large around as one could reach and twice as tall as a man." In 1680, Taos, under the leadership of a Native American named Pope, orchestrated the revolt of the pueblos, one of the pivotal events in Southwestern history.

While a visit the ruins of the Salinas and Pecos pueblos will take you out of the main stream of tourism, a trip to the ruins of the 6th to 15th century Pueblo Grande, an important trading center in the old Hohokam region, will take you straight into the midst of the booming city of Phoenix. The Hohokam (a Puebloan tradition centered in southern Arizona and northern Sonora and distinguished by elaborate irrigation systems, innovative craftsmanship and Mesoamerican-style ceremonial platform mounds and sunken ball courts) capitalized on the entire prehistoric trade network, including the trails from the Southern Plains to the Pacific coast as well as those from Mexico to Utah. According to John P. Andrews and Todd W. Bostwick in Desert Farmers at the River’s Edge: The Hohokam and Pueblo Grande, "The Hohokam traded for a number of raw materials and finished craft products, and may have obtained these items by trading their cotton, surplus crops, and their shell jewelry… At Pueblo Grande, more than 50 types of imported ceramic wares have been recovered during excavation." According to Andrews and Bostwick, Pueblo Grande – more than a mile across at its peak – encompassed, not only a large platform mound, but also "two and possibly three ballcourts, several major irrigation canals, trash mounds, houses, courtyards, plazas, hornos or ovens, compounds, storage pits, cemeteries, and various other cultural features." It also included a "big house," a "large multistory adobe building…" Pueblo Grande is located just northeast of the Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport, along the north side of the Salt River.

Of all the Puebloan trade center ruins, I suspect that the late prehistoric Paquime would rank as the most culturally diverse. Located on the Casas Grandes River in northwestern Chihuahua, Paquime had roots in all the major Puebloan traditions, including the Hohokam, the Mogollon (of southern New Mexico and northern Chihuahua) and the Anasazi (of the Colorado Plateau), and it drew inspiration from Mesoamerica. It appears to have served as the gateway for a network of mercantile trails leading into the Southwest. It provided warehousing for trade goods, exemplified by the nearly 4,000,000 salt water shells discovered by Di Peso’s archaeological team during excavation of the ruins. It operated the bustling marketplace. Reflecting community planning, Paquime comprised an apartment complex, private courtyards, domestic storage, a subterranean well, a sweat bath, slave dungeons, warehousing, artisan work areas, ceremonial rooms, ceremonial item storage (mostly bear bones), and a human-skull trophy room. The public area included the open market, a plaza, effigy mounds, ceremonial mounds and ball courts. Paquime came to a violent end when some unknown enemy attacked the community, killing hundreds of its citizens, burning the support beams and demolishing the walls of structures, and smashing the sacred icons of the Paquime religion. Paquime lay in ruin, as if frozen in time, for five centuries, until unearthed by Di Peso’s trowels.

Rio Grande Bend near Boquillas Canyon (Big Bend National Park, TX)

By Glysiak - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32441150

The Grand Indian Crossing

Some 300 miles down the Rio Grande from the Paso del Norte ford, at the southernmost tip, or "elbow," of the great southeast-to-northeast "big bend" in the river, you will find the Grand Indian Crossing, that "very wide, well beaten, and…much traveled thoroughfare..." of the 19th century Comanche War Trail. For the Comanche and Kiowa warrior parties returning from their plundering of Mexican settlements in Chihuahua and Coahuila, the ford would have been a milestone in a successful raiding expedition and the long journey home. For their captives, it would have been a forlorn symbol of fading hope, a lost family and a fearful future.

To reach the ford, follow the paved road from the Big Bend National Park headquarters and visitor center southeast toward the Rio Grande Village visitor center for approximately 15 miles. There you will come to an intersection with an unpaved road which the National Park Service describes as "Primitive," a signal that you will likely need a "four-wheel drive, high-clearance vehicle" to proceed farther with confidence. Follow the primitive road generally southwest past the old, abandoned Mariscal mining community then generally south to the Grand Indian Crossing, just upstream from Rio Grande’s Mariscal Canyon—altogether a distance of about 30 miles from the turnoff at the paved road. Before you leave the visitor center, secure a good park map and a road condition update from the Park Service personnel. As a precaution, take food and water to tide you over in the event you have a breakdown. Not many park visitors travel the road.

The ford lies in one of the more isolated corners of our nation, in the midst of the thorny basins of the Chihuahuan Desert and the rocky slopes of volcanic hills and mountains. It was a terrible and punishing landscape for herds of hundreds of hard-running horses. Should you go there in the summer, it will become clear why the Comanches and Kiowas chose the cooler month of September – a time of year that fearful Mexicans referred to as the "Comanche Moon" – to begin their annual raids of the settlements to the south.

Prehistoric road. From Chaco Roads Project Phase 1, A Reappraisal of Prehistoric Roads in the San Juan Basin 1983. BLM, Chris Kincaid.

The Chacoan Roads

If you are intrigued by Chaco Canyon’s mysterious road network, I suggest that you hike the park’s Alto Mesa Trail, which will lead you to a part of one of the roads. The trail ascends from the canyon floor to its rim through a narrow break in the wall immediately behind the Kin Kletso Pueblo ruin. It follows the rim generally eastward for perhaps a half mile, passing two stone basins which the Chaco Anazasi cut into the bedrock for some reason now inexplicable. At a striking overlook just above and behind the famous Pueblo Bonito ruin, the trail turns north, toward the Pueblo Alto complex of ruins, where, apparently, several of the Chaco roads converge. On the trail between the overlook and Pueblo Alto – a distance of perhaps three quarters of a mile – you will discover remnants of one of the roads.

Masonry curbing. From Chaco Roads Project Phase 1, A Reappraisal of Prehistoric Roads in the San Juan Basin 1983. BLM, Chris Kincaid.

You will find stretches which the Anasazi obviously cleared of rubble and bermed with loose stone. You will see rock outcrops which they graded down with stone and wooden hand tools to facilitate their passage. From Pueblo Alto, the trail leads eastward for roughly three quarters of a mile across the region’s high desert sage landscape, taking you back to the rim and a view of "Jackson’s Staircase." That precipitous and dangerous pathway may have served for pilgrims’ ceremonial descent to the canyon floor. Altogether, the round trip distance on the Alto Mesa Trail is just under five miles. You would likely spend several hours on the hike. Although the trail would rank as no more than moderate in difficulty, you should take appropriate precautions, especially on a hot summer day. Inquire about maps and trail conditions at the Chaco Canyon Visitor Center.

The Native American Legacy of Trails

The juxtaposition of our super highways and the Native American trails provides a measure of how far we have come technologically. In our sleek sedans, we cover 75 miles in an hour. Foot-bound hunting and gathering bands of Native Americans covered perhaps 20 miles in a day. In our double-trailer semis, we transport 20 tons of commodities and possessions. They transported what they could carry on their backs. In our buses, we move crowds of people from city to city. They moved in small extended families across an isolated landscape. We travel in plush seats and air-conditioned comfort. They trekked, with small children, over rocky and sandy desert basins and towering mountain ranges in the raw cold of winter and the searing heat of desert summers.

For all our technology, however, we will never equal one accomplishment of the Native Americans. They came first.

More Trails

Desert Trails

Coronado Expedition from Compostela to Cibola

Coronado Expedition from Cibola to Quivira then Home

Chihuahua Trail

Chihuahua Trail 2

The Juan Bautista De Anza Trail

Jornada del Muerto Trail

Santa Fe Trail

The Long Walk Trail of the Navajos

The Desert Route to California

Bradshaw's Desert Trail to Gold

A Soldier's View of the Trails Part 1

A Soldier's View of the Trails Part 2

Share this page on Facebook:

The Desert Environment

The North American Deserts

Desert Geological Terms